When 30-year-old hiker Marco Williams journeyed from his home in Prince George’s County, Maryland, to visit Devil’s Bathtub in deep Virginia in June of last year, the outdoor enthusiast never imagined that a stop for gas would present him with a warning that potentially saved his life.

In a TikTok that has now been viewed 2.5 million times, Williams told his followers that on his return home, traveling along Route 119, he visited a small service station in Kentucky to refuel and grab some snacks.

“The cashier was like, ‘You best not be around here after dark. This is a sundown town,’” he said.

A sundown town as explained by James W. Loewen, a former sociology professor at the University of Vermont and author of Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, refers to a town, neighborhood, or community with a wholly white population, created intentionally by systematically keeping out ethnic minorities.

“You best not be around here after dark. This is a sundown town.”

“A lot of African Americans don't really travel to certain parts of the country. I did not know this. I'm being naive, traveling, but they don't travel to certain parts of the country because certain people have those mindsets,” Williams told BuzzFeed News. “The racism and prejudice is still in those towns, the mindset from the Jim Crow era is passed down, and these people have no exposure because they don't get out.”

According to Loewen’s rolling database, at least 60 of Kentucky’s 782 towns are believed to be or previously have been considered sundown towns. But these towns aren’t just in the South. They are all over the US and concentrated particularly in the Midwest, he says.

Despite the phenomenon, historical references to sundown towns are few and often wrapped into tales of the expulsion of Black communities in places like Forsyth County and Anna, Illinois, which is allegedly known colloquially to be an acronym for “Ain’t No Niggers Allowed.”

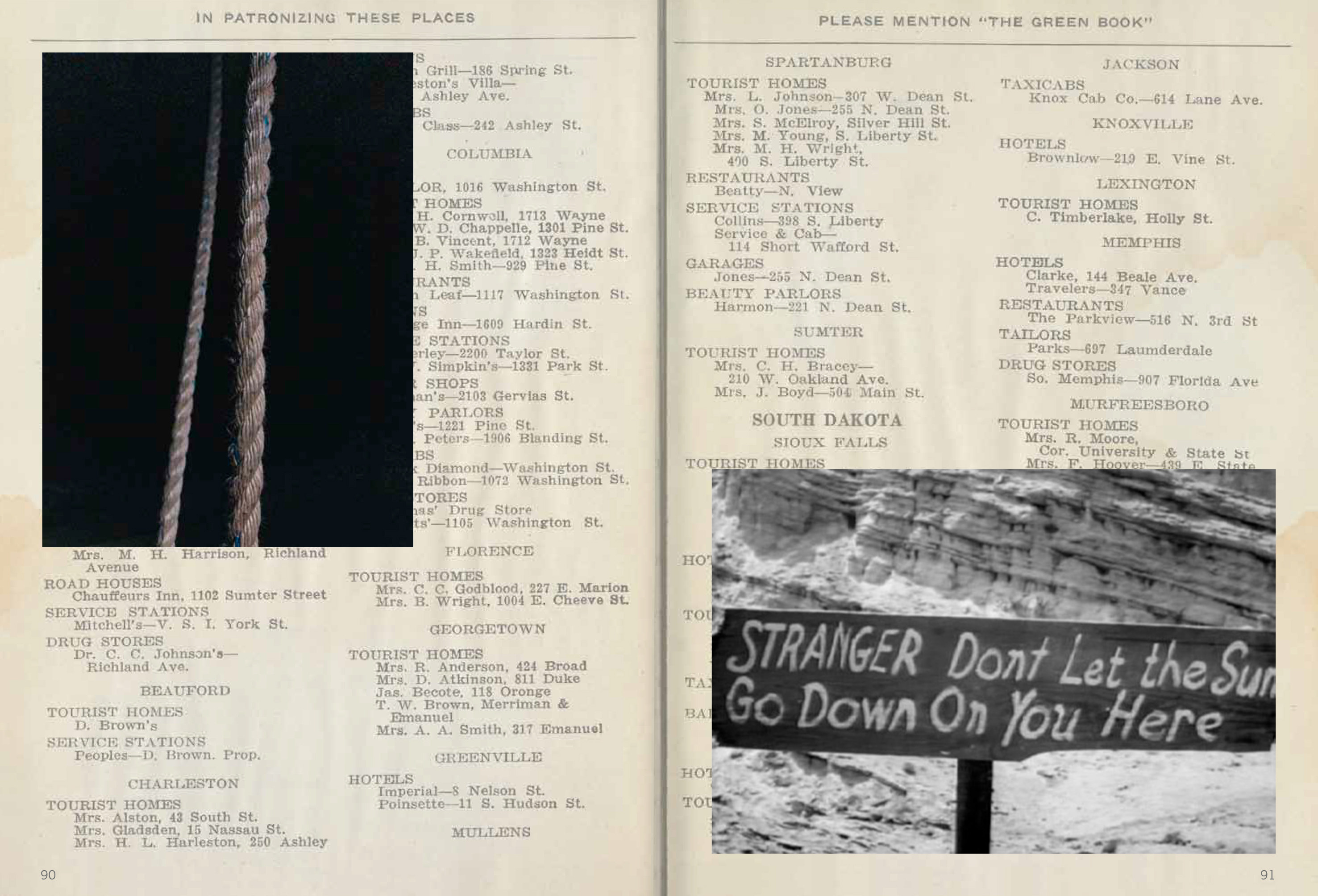

In her 1969 memoir I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, the late poet Maya Angelou describes Mississippi with the phrase, “Don’t Let the Sun Set on You Here, Nigger, Mississippi.” The same sentiment would appear on signage posted at city boundaries of sundown towns, making clear that Black people were not welcome and risked their lives if they dared to defy the decree. Last year the concept was portrayed on the premiere episode of HBO’s Lovecraft Country in which the three protagonists are forced to flee a town while being stalked by a police officer.

Activist organizations have used the term more recently. In 2017, the NAACP issued a travel warning for the entire state of Missouri, a first for the organization. The decision was in response to a bill designed to limit discrimination lawsuits by making changes to the Missouri Human Rights Act. Senate Bill No. 43 would require employees prove that their protected characteristics were a “motivating factor” for being discriminated against when previously the requirement was that simply showed it was a “contributing factor.”

The NAACP also referenced anecdotal examples of hate crimes, and data which showed Black motorists were 75% more likely to be pulled over and stopped and searched by police enforcement than their white counterparts. (The state of Missouri offered no public response to the NAACP but did make a Black woman the face of its tourism campaign last year.)

And in 2020, a group called the Defund San Antonio Police Department Coalition issued a travel warning for San Antonio, labeling the city as a sundown town. "A travel advisory has been issued to warn that any Black people in or traveling to San Antonio use increased caution when visiting the city due to the city's policing policies that put Black Lives in danger," wrote organizers in a press release.

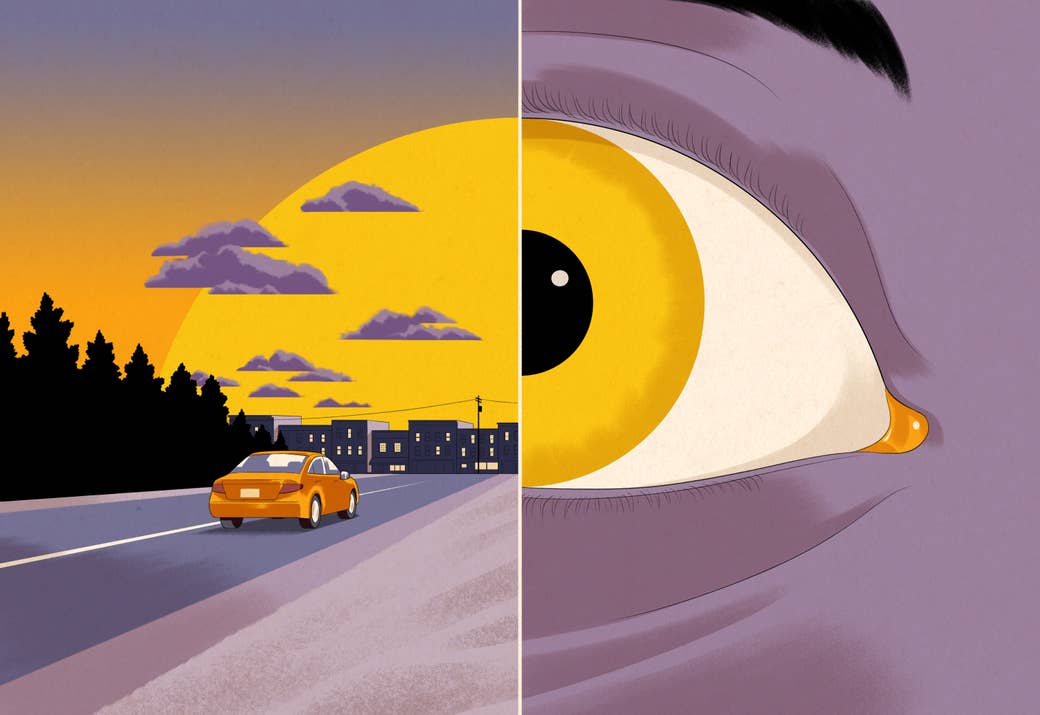

Today, the legacy of sundown towns continues to cast a shadow on the tradition of the great American road trip, creating additional challenges for Black motorists who dare to journey off the beaten path.

Williams took up hiking as a hobby in response to the pandemic. In June 2020, he made the seven-hour journey by road with a non-Black friend to visit Virginia’s hidden gem, Devil’s Bathtub.

“When I usually travel, I’m going to cities like New York, Miami, Atlanta, major populated cities. I wanted to get in touch with my nature side and I wanted to explore the rural American South,” said Williams.

In recent years, the angst of being a Black motorist has been captured with the hashtag #DrivingWhileBlack. As Americans flock to the open roads in a bid to reclaim their summer after more than a year of restrictions, the freedom and excitement of the road trip isn’t without caveats for minorities looking to venture to less diverse destinations.

“En route, there were a bunch of Confederate flags, a lot of ‘Make America Great Again’ flags, there's even a few Klan lounges in South Carolina that we came across,” said Williams. “It’s when you veer off to the back roads that don't connect to the highway, that's when you find yourself in trouble, and it sucks because the hiking spots [are] in these back wooded areas like West Virginia and Kentucky.”

Williams said he didn’t believe the cashier who suggested he leave town before sundown did so with malicious intent. “I don’t think she was being racist toward me. If anything I got the energy that she was looking out for me so I believed her and got out of there,” he said.

Rather than challenge the convention and try his luck, Williams and his companion quickly got on with their journey back to Maryland, because “dead men tell no tales.” Despite the experience, he said he would be down to do it all again, but “would definitely be cautious.”

Exercising caution and traveling with intentionality is a key feature for Black motorists, and is a philosophy that travel blogger Sojourner White is guided by.

Honoring the etymology of her name, Sojourner, White discovered her love for voyages on the road as a child traveling with her family from their hometown of Milwaukee.

“I traveled throughout my childhood,” White, who runs a blog called Sojournies, told BuzzFeed News. “Milwaukee to Louisiana, St. Louis, Michigan, Atlanta, just because we have family spread out. We were always hopping in the van or the truck with me and my four brothers, exploring the US, and then it just kind of grew from there.”

White is familiar with sundown towns. The legacy of fear about where Black travelers will not be welcomed is something that frequently comes up in her network of bloggers.

“That’s the other part of the pandemic: I have not interacted with white people as much, and so I find that I deal with racism less.”

“You hear people say, ‘My parents don’t want me to travel.’ They say it’s because of racism, and so it’s also a cultural thing with sundown towns,” she said. “The aftereffects of it, even though they still do exist. As the younger generation, I would say millennials, we’re the ones who are like, No, we’re gonna explore. We’re gonna kind of go out here. But it took a lot for people to get there.”

White, who is also a social worker, said that when traveling on American roads, details like planning where to stop made all the difference lest Black drivers unknowingly find themselves “in the wrong spot.”

“It’s like, OK, we can stop in St. Louis, intentionally stopping in the bigger cities to avoid any type of conflict, granted that even the cities have their issues, but it’s not like going to a space and being the only Black person for thousands of miles,” said White.

Like many travel content creators, the pandemic limited her ability to travel internationally, so she focused on local excursions.

Because there were fewer travelers during the pandemic last summer, White said she was able to indulge in the road trip experiences she wouldn’t have otherwise considered.

She drove to Oshkosh, a town in northern Wisconsin. “I’ve been doing a lot around Wisconsin recently with the pandemic, and seeing things I didn’t know were tourist attractions. But the other side of that is I didn’t really explore Wisconsin a whole lot because of what I heard about being Black in other areas,” said the 26-year-old.

“That’s the other part of the pandemic: I have not interacted with white people as much, and so I find that I deal with racism less,” she said.

“When I was going up there last fall, all you saw was Trump signs, ‘All Lives Matter’ type of things, or ‘Blue Lives Matter.’ It wasn’t everywhere, but that’s part of the reason why I don’t have a lot of road trips around the US to go see sights.”

In his book about sundown towns, Loewen writes about how the social fabric of these towns remains very much steeped in the white supremacist values they were founded on even if their populations have become more diverse over time and suggests that residents are likely to hold a reverse attitude to travel.

“There’s all kinds of people who live in sundown towns who do not want to, for example, go to Washington, DC, and visit the Smithsonian museums and see the Capitol and do all the things that you do in Washington DC, because it’s too Black,” he told BuzzFeed News. “And the same thing, they really don't want to go to Atlanta, an actual tourist destination, they don't go. Chicago is also a problem, all them Black folks.”

Loewen said the number of sundown towns is much higher than the general public would guess. But despite their prevalence, little work has been done to interrogate the history of these communities to reconcile with the legacy of racism and the second-generation sundown issues that can present themselves even where the policy is no longer formally enforced.

His website hosts a database and allows user-submitted information for better verification. The project, he says, is the world’s “only registry of sundown towns,” and he hopes will dispel what he describes as the Hollywood myth that these towns exist almost exclusively in the South.

“There are five Hollywood movies about sundown towns and all of them are set in Mississippi, except one that's out in Georgia. It sets us back in race relations because the whole rest of the country is like, Yeah, we’re all right. This is a good country. Everything’s fine except those nasty white Southerners with all them sundown towns, and they used to have slavery and all that. It’s a national problem. It’s more a Midwest problem than it is a Southern problem,” said Loewen.

The contentious matter of where to stop and what areas are accessible for Black motorists is embodied by The Negro Motorist Green Book, written by postal worker Victor Hugo Green and first published in 1936.

It was hailed as the Black travel bible and was considered a quintessential aid for Black people traveling across the US. The book would let motorists know what establishments they could expect to receive service and also issued warnings about the towns where it was dangerous for Black people to stay after sunset.

In his photo book A Parallel Road, Boston author and photographer Amani Willett examines the Black American road trip over the past 85 years and borrows from pages of The Green Book in telling that story.

“The Green Book is an amazing cultural artifact that operates both as a condemnation of the history of America and its horrific legacy of racial oppression while at the same time being a powerful document illustrating the creativity and resilience of Black Americans,” said

Willett. “The guide shows how we as a people have always found ways to navigate a system and country that is an oppressive force.”

The photography professor told BuzzFeed News how ideas around freedom and traveling had long been assumed by Americans as rights, rather than privileges, but that’s not the case for Black people.

“The Black American experience on American roadways has negated the myth of travel as an American freedom available to all. At best, Black Americans have experienced less mobility than White Americans and at worst they have been met with intimidation, fear, profiling, and physical harm or death,” said Willett.

Beyond the observations detailed in his photobook and his own research into sundown towns, Willett is cautious about dividing the country into areas where Black people can and can’t go when recent events have highlighted that racism can be found everywhere, making the reality much more sinister.

“There are certain areas of the country where Black people know they have to be more careful than others but the truth is, as we’ve seen throughout the social media era, injustices and racial profiling exist in all corners of our country,” he said.

Martinique Lewis, president of the Black Travel Alliance and creator of the new ABC Travel Greenbook, a modern-day interpretation of The Green Book, with a global focus of connecting Black travelers with touch points anywhere in the world, agrees.

“Black people are always alert, and it doesn’t matter if that’s in Miami, Vegas, or if it's Pigsty, Alabama, you know and feel when something is not right,” she told BuzzFeed News. “The reality is we deal with racism on a daily basis in America.”

With her publication, Lewis revives the Black business aspect of the original Green Book with the intention of directing Black travel dollars their way. She also prefaces each destination with a safety assessment and encourages explorers to enjoy themselves but to also remain alert.

Lewis’s logic is that “if you can find one Black business, you will find the rest of the Black people,” and connecting with people who look like you can make all the difference to your experience.

Willett agrees that accessing a Black network is “critical” for Black travelers to understand the historical legacy of destinations and their routes in preparation for “potentially dangerous encounters.”

“I’m very in tune with my energy and sensing when I’m not welcomed in an area or a room, so it’s like certain areas, you do get that vibe and that feeling where you’re like, I probably shouldn’t be here,” Williams said.

As the Black travel blogger community begins to travel again, White believes that they represent the modern-day ambassadors for where to go and where to avoid.

“We’re the ones who test it out first, we give our reviews, and so I think we’re a really great resource, because it’s honest,” she explained. “We have nothing to lose.”

Above all else, photography professor Willett believes that it’s imperative that Black Americans continue to travel around the country in defiance of “the mechanisms of oppression and intimidation” that have been designed to restrict the movement of Black motorists. “In this way, we can demand equal participation in the pursuit of the freedom that the road and the great American road trip have supposedly offered all Americans.” ●