For two weeks every August, the Iowa State Fair becomes the center of the regional universe. It’s unlike other state and county fairs I’ve attended out West: It’s cleaner and less dusty, and there are paved streets. Some senior citizens zoom by on scooters; other people hitch a ride on cabooses towed by John Deere tractors. And then there are the political candidates, wandering around, making a show of relatable fair-food eating, glad-handing, and introducing themselves to everyone, because everyone could potentially sway their local caucus, the traditional manner in which the state helps determine the trajectory of the presidential election to come.

Walking the main thoroughfare, 52-year-old Steve Bullock, the governor of Montana, gets stopped by a woman asking to take a selfie. She didn’t know who he was — she just knew he was running for political office. “You can tell by the clothes,” she said. On that day: a blue oxford, Levi’s jeans, a Montana summer tan, and the kind of cowboy boots that signal Bullock as someone who doesn’t live — and who has, in truth, only briefly lived — anywhere with a population of more than 30,000 people.

“Iowa is kind of like doing the stations of the cross,” Bullock joked at one point in the three days he dutifully spent going through them. At the state fair, he ate pork belly on a stick. He ate a hard-boiled egg on a stick. He ate a pork chop not on a stick, and talked with the guy who sold it to him about bilateral agreements and the Trans-Pacific Partnership. He went on the Ferris wheel and took photos and wondered, “Can I still Snapchat this, even if I’ve already taken it?” He exclaimed, “Did you know that 31 piglets were born here last night? The vet just told me!”

He drank a local IPA on draft at the Triple-A ballpark in Des Moines, and a Coors in a bottle on a farm out in Altoona. He showed up at a dozen events over three tightly packed days; he sat for interviews with the local press and made pitches to big-name donors.

“No offense, but how’s a guy from Montana ever gonna win?”

When Bullock first arrived in Iowa, he headed straight to a lunchtime gathering of two dozen Polk County Democrats in Des Moines who were there to support secretary of state candidate Deidre DeJear, eat some mini ham-and-cheese sandwiches, and listen to a political pitch from a guy most of them had never heard of. “No offense, but how’s a guy from Montana ever gonna win?” one attendee, a self-described “Biden Boy,” told me as Bullock shook hands around the room. “It’s like one of the four states I’ve never even been to.”

When Bullock started to speak, some of what he had to say was standard messaging in the lead-up to the midterms: “Showing up is a big piece of how we win” and “It’s not enough to just be against Donald Trump.” But Bullock’s personal pitch made people in the room pay attention: In 2016, 20% to 30% of the people in Montana who voted for Trump also voted for him. He got Medicaid expansion through a Republican-dominated legislature, with a demographic makeup much like Iowa’s. And he’s worked with the state legislature to shed light on what campaign finance activists have termed “dark money” — political contributions from outside interests that don’t have to disclose their donors — in Montana politics. When Bullock talks about getting the Medicaid expansion through, someone lets out a low, appreciative whistle.

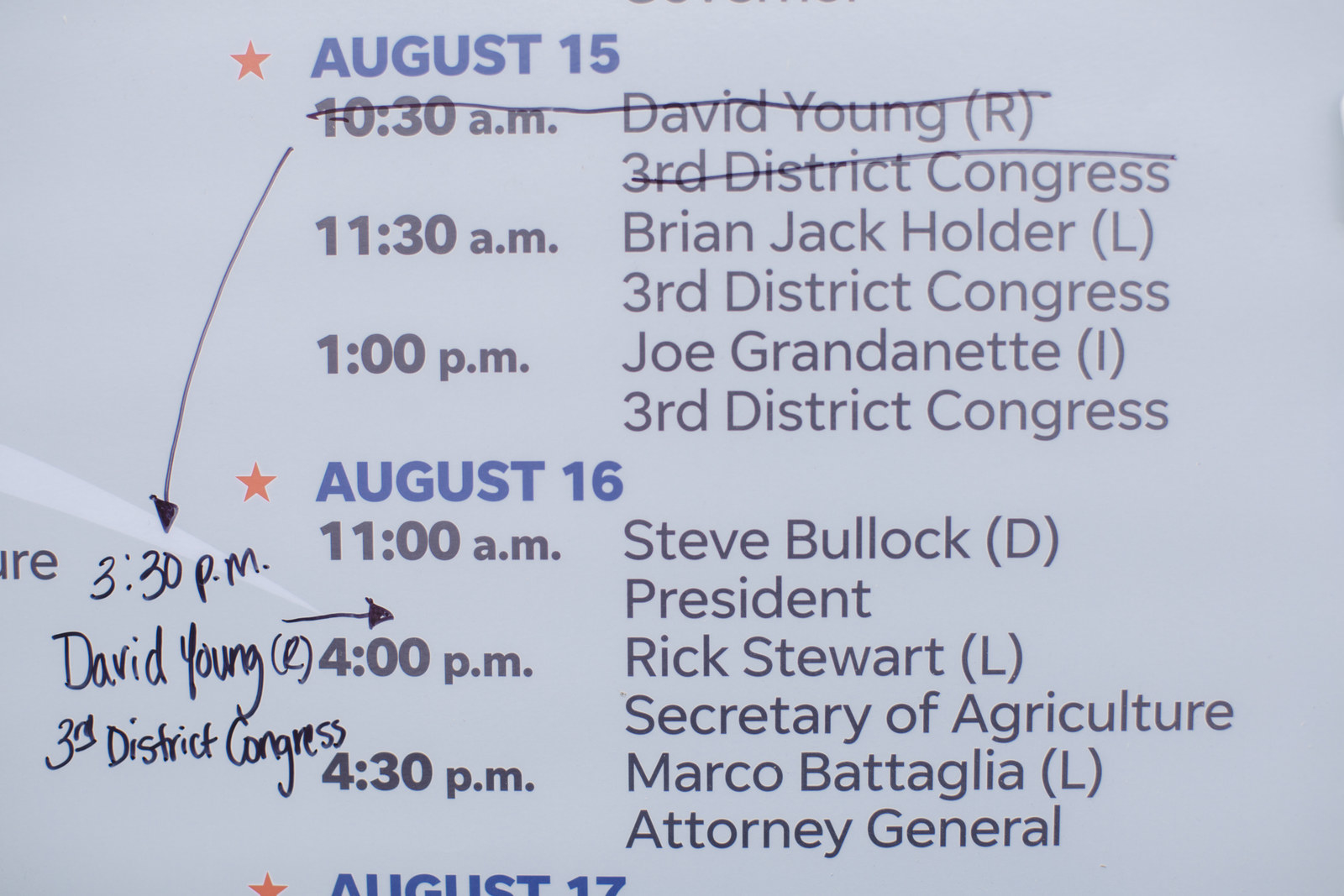

That sort of reaction is what Bullock’s attempting to re-create the next day at the Soapbox, an Iowa Fair tradition where local and national candidates deliver the best version of their stump speech to a modest crowd on the side of the thoroughfare. On the Soapbox schedule, Bullock’s name is listed along with two dozen other local and national candidates, each with a word under their name to signal which office they’re chasing. Under Bullock’s name, it says “President.”

That explicit reference to his ambitions is a small annoyance for Bullock, who remains coy concerning the official status of his campaign. And yet, of course, that’s why he — and John Delaney, the House Democrat from Maryland who spoke the day before, and Julián Castro, the former San Antonio mayor who will speak the day after — is here. That’s why he’s taking off his sunglasses so people can see his eyes, why he’s trying to figure out how to make himself heard over the big wheel races happening just feet away. That’s why, in his Soapbox speech, he makes his most reliable joke: “A lot of people show up here and try to make some attenuated connection to Iowa,” he says. “I can’t even imagine what that might be like for you. So I won’t tell you that my great-great-grandfather homesteaded in Henry County in 1856.” (Cue laughter.) “And I won’t tell you my mom was born in Ottumwa.” (More laughter.)

It’s why he launches into his dark money pitch straightaway. He talks about the Citizens United Supreme Court ruling and how unlimited corporate spending has impacted our elections. “Think about 2004. Five million dollars of dark money, undisclosed money, was spent in our federal elections. Fast-forward eight years, and it was $300 million. A six thousand percent increase in just eight years in dark money pouring into our election.”

And that’s why he tries to establish the stakes of that political spending as a central concern to the future of democracy: “If we wanna address all the other big issues in our electoral system, in our political system, if we really want to address income inequality, if we want to address health care,” he continues, “you’re not gonna be able to do it unless you also address the way money is affecting our system.” This, above all else, is the Bullock pitch: You wanna do all this progressive work? None of it can happen until we excise the very root of the blockage.

Later in the speech, Bullock avers that “The Democratic Party didn’t necessarily change; we just haven’t been able to figure out the ways to speak to people off of the coasts. And if we can’t speak the language of Iowa or Michigan or Wisconsin, even if you get an electoral majority you’re never going to have a governing majority.” He gets a solid set of vigorous Midwestern head nods. Afterward, a thirtysomething approaches and shakes Bullock’s hand. “I really admire what you’re doing with net neutrality in Montana,” he says. He lives out of state, but his mother, a former educator who self-identifies as an “MSNBC Mom,” is here from the Quad Cities, two and a half hours to the east. “I asked to get my picture with him,” she tells me, giddy. “I like him a lot. I think it’s gonna work. He’s cute!”

“If we elect the guy I like, we’d never get anything done. I think we probably need a guy like Bullock.”

All morning, the Iowa humidity had been building, and after Bullock finishes his speech — and, unlike many Soapbox speakers, takes questions from the crowd — a gray cloud bursts into a downpour. A Des Moines man named Gene ducks under an awning beside me. “Bullock’s more moderate than my personal politics,” he says. “But if we elect the guy I like, we’d never get anything done. I think we probably need a guy like Bullock.”

Bring up Bullock’s name to the progressives currently working to elect an incredibly diverse swath of midterm candidates, and the response is generally a variation on “Do we really need another white guy?” While he’s not a “coastal elite,” his typicalness, at least when it comes to race and gender, has the effect of blunting his achievements — especially when coupled with his talk of respect and conciliatory politics and reaching out to Trump voters, which may seem like particularly white-guy positions to take. Or at least too meek and too nice to effectively stand up to the inflammatory likes of Trump. The week before Bullock showed up to eat pork products at the fair, Michael Avenatti was in Iowa, telling Democrats to “fight fire with fire,” admonishing the party for bringing “nail clippers to a gunfight.”

Bullock might be able to win high office in a state like Montana, or even in a state like Iowa. But as Justice Democrats codirector Alexandra Rojas recently told BuzzFeed News, in reference to a potential Joe Biden presidential run, “The base right now wants really refreshing candidates.” Will #Resist warriors get fired up for Bullock as the Democrat to take on Trump in 2020, especially with candidates with established fanbases like Cory Booker, Elizabeth Warren, and Kamala Harris in the mix?

If there is something that sets Bullock apart from other potential white-guy presidential candidates whose politics strike progressives as too moderate, it’s probably the state he governs. In many minds, progressive and conservative, Montana still possesses that rarified Western aura: a place of unrivaled beauty and open, frontierlike land, but also unspoiled, uncorrupted by the partisan bickering that’s divided the rest of the country. Whether or not this is true (it’s largely not) matters less than how Bullock and his team can wield the idea of Montana and his embodiment of it. Steve Bullock, Montana Presidential Candidate, isn’t just from flyover country. He’s from one of the last largely uncivilized parts of the West. And he’s a Democrat! And Trump voters don’t hate him! And he doesn’t hate Trump voters! Imagine that.

Most people in the US don’t know much about Montana, and know even less about its governor. But from one perspective, Bullock’s anonymity is an advantage. Unlike Hillary Clinton, who battled four decades of accumulated narrative about who she was and what she stood for, the ignorance around Bullock allows him to write his own, unexpected, and — at least for the Democrats who saw him in Iowa — impressive story of how effective he’s been as a leader.

So how can a straight white man move forward amid an atmosphere, at least among Democrats, that’s resistant to, or even repelled by, the idea of more straight white men in power? By trying to reach voters, at least in pivotal primary states, the old-fashioned way: one-on-one, on the ground in Iowa, while other candidates are keeping their message national. Bullock is going for that Jimmy Carter, decent dad appeal. He’s the opposite of Trump, who is definitionally not nice, intentionally abrasive, purposefully uneducated. His strategy isn’t to eclipse Trump, but to offer an entirely different narrative — not to make America great again, but to make politics nontoxic, or at least less toxic, again.

If Bullock makes a serious run for president, it’ll be because what his candidacy represents — common civility, decency, and the fight against corruption — outweighs what “white male politician” has come to represent, especially for the women and people of color so crucial to the Democratic voting coalition. In our current cultural moment, that’s a big ask. The only way to do it: by speaking passionately and convincingly to the issues that Democratic voters care about. Bullock’s betting that if he can do that, it doesn’t matter if most people don’t know his name right now. There’s time. They will.

This is Bullock’s third visit to Iowa over the last six months, and as was the case with those previous visits, he’s shepherded by Tom Miller, the nine-term Iowa attorney general so popular he’s running unopposed. “They tried to find a Republican to run against me,” Miller told me. “But it was too hard, because too many of those Republicans were voting for me.” Miller has the affect of a slightly bumbling and much-beloved grandfather; he’s known for his role as one of Barack Obama’s primary stewards leading up to the 2008 caucuses, long before “Barack,” as Miller refers to him, became a household name.

When Miller shows up with a candidate, people in Iowa take notice. And unlike many other intermediaries showing candidates around the state, Miller’s not on a payroll. He and Bullock go back to 1999, when Bullock was chief deputy attorney general of Montana. Later, they'd meet at the National Association of Attorneys General — an organization of which Bullock would later become president. He’s currently the chair of the National Governors Association. Previously, Bullock was president of his high school student body. His freshman year of college, he ran for class rep by driving out to Cal Poly University, borrowing a sheep, putting it in the back of a friend's Chevette, and driving it through campus with a sign that read, “There’s more to Montana than just sheep. A vote for Bullock is a vote for Ewe." Two years later, he was student body president. Bullock loves to be president.

But before his ascent in Montana politics, Bullock was just a kid growing up in Helena, Montana, delivering newspapers down the street to the governor’s office. He spent summers as a guide for the Gates of the Mountains boat tour, just outside of town, and can still recite the 20-minute spiel, in full, on request. As a high schooler, he applied to a variety of elite colleges, hoping to get into one on what he half-jokingly calls Montana Affirmative Action. He ended up at Claremont McKenna, a small liberal arts college outside of LA — a place he’d never even visited until his first day of school. From there, he went on to study law at Columbia University.

When Miller shows up with a candidate, people in Iowa take notice.

Just weeks before Bullock graduated from Columbia in 1994, his nephew — an 11-year-old attending a Butte elementary school — was shot and killed, then the youngest victim of a school shooting. It’s an event that, until very recently, Bullock declined to discuss in public. This May, however, following the Santa Fe school shooting in Texas, he wrote an op-ed pairing that experience with that of his son shooting his first deer during hunting season — both of which, he says, shape his thinking on gun policy, which includes background checks, banning semiautomatic weapons, and rejecting plans to arm teachers in the classroom. It marked the first attempt to make gun control — a mostly verboten topic in Montana politics, no matter one’s affiliation — part of his platform, rooted in the sort of compelling personal experience that would resonate with national audiences.

After graduating, Bullock resigned himself to a decade in the corporate trenches of a New York law firm, working off his six-figure debt, until he learned his father had stage 4 cancer. He returned home to Helena, with a promise of loan forgiveness from Columbia if he worked in the public sector, rising through the Montana Justice Department to the role of acting deputy attorney general. In 1999, Bullock, then 33 years old, launched an ill-advised bid to become the state’s attorney general. At a small gathering of the Iowa Attorney General’s Office, he jokes about the campaign: “I don’t even think my family voted for me,” he said. “I just got killed.” He retreated to a private-sector job in Washington, DC, for three years, but returned to Helena in 2004, launching a second — and this time successful — bid for the attorney general spot in 2008.

That’s when Bullock first started going after his political white whale: dark money in politics, which, in a series of twists and turns, led him all the way to the Supreme Court. Bullock’s crusade didn’t ultimately affect Citizens United, but it nonetheless positioned him for his 2012 run for governor. Once in office, working with a bipartisan group of lawmakers, he’d eventually sign the Montana Disclose Act into law, which requires any groups funding election-related communication to disclose their donors. Earlier this summer, he signed an executive order requiring all recipients of government contracts to disclose political spending; he features prominently in a dark money documentary, made by his high school classmate, currently making the indie circuit rounds.

Consciously or not, he’s spent eight years solidifying a reputation — as the “anti–dark money guy” — from which to run a presidential campaign that would match the current anti-corruption moment, arguably most embodied, to this point, by Sen. Bernie Sanders. Where Sanders’ (very successful) pitch to voters channeled anger and disgust, Bullock’s is its calmer, lawerly counterpart, filled with examples, however specific to Montana, of how he’s actually worked to shed light on dark money sources. And yet: If your principal motivation as a voter is anti-corruption, who would look to Bullock, instead of Sanders? Those whose loyalty was to Clinton, perhaps, but those voters seem more likely to gravitate toward candidates like Elizabeth Warren, Kirsten Gillibrand, or Kamala Harris. At this point, the success of Bullock’s anti-corruption image might hinge on a Sanders-less primary. And that’s a big, uncertain bet to make.

In the governor’s office, Bullock succeeded Democrat Brian Schweitzer — a charismatic politician who, like Sen. Jon Tester, is the kind of classic Montana Democrat who’s an avowed supporter of women’s reproductive rights and the social safety net, but who’s also most comfortable in a pair of muck boots. Tester’s most iconic Montana characteristic is his missing three fingers, lost to a meat grinder accident as a young boy; Schweitzer’s was vetoing bills with an actual branding iron in an outdoor ceremony. Bullock is less, well, rustic. No number of fishing stories can hide the sliver of erudition breaking through the folksy veneer. He’s gregarious in person, but reticent with the press; in his stump speech, he drops in words like “opined” and “deleterious.”

“Schweitzer had that thing where he can just suck all the air out of a room,” Chuck Johnson, who covered Montana politics for the major Montana newspapers for decades, explained to me. “Bullock’s got a different type of personality: It allows him to go into that room and talk to each different type of person in there.” Still, Montanans often complain that Bullock’s just not very exciting. Earlier this year, the president of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, Land Tawney, told me that he’d never really seen Bullock get worked up about anything — until a public lands rally last year in Helena. (Public lands make up 29% of Montana, and campaigning on a platform of protecting them — which includes preserving access for all Montanans, whether to hunt or hike or fish — is one of the ways that Democrats get elected.) Bullock spoke at the rally, which was held in the rotunda of the capital and was caught on video. “He was whooping up the crowd, yelling, a big ol’ vein just pulsing his forehead,” Tawney recalled. “And I was like, this is it, I’ll follow this man anywhere.”

As excited as voters get about protecting public lands in Montana, it’s a very Western issue — a plank, but hardly a foundation, for a presidential campaign. And at this point in the process, in this very particular election climate, campaigning as a Democrat seems to be much less about specific policy issues and much more about how you campaign: where you’re willing to go, how obsessively and aggressively you put yourself out there, how effectively sound bites from your speech can be turned into Now This memes and viral videos.

Bullock is not a flashy, new media–style campaigner; there’ll be no footage of him skateboarding in a burger joint parking lot.

Bullock is not a flashy, new media–style campaigner; there’ll be no footage of him skateboarding in a burger joint parking lot like Beto O’Rourke, who is running against Ted Cruz for Senate in Texas. But like O’Rourke, Bullock prides himself on going places where most Democrats don’t — small towns where he only received a handful of the vote — and that campaign philosophy seems to match the current political moment in the US. For a Democrat to win in Montana today, they not only have to appeal to traditional quasi-urban voters (the biggest city, Billings, barely tops 100,000) but also peel off enough rural voters to fend off the newly powerful block of out-of-state conservatives who’ve flocked to the state, largely from California, in recent years.

In practice, this means a whole lot of driving: to the ranches of the far east, to the seven different Native American reservations that quilt the state, to the labor stronghold of Butte and the wealthy snowbird hippies of Big Sky and Whitefish, to the farmers of the Hi-Line region and coal-dependent counties of the southeast. It means catering to a state that’s actually about the square footage of 10 states in one, and code-switching as you do. “We always used to tell someone running for state legislature that it’s not about how much money you raise, but how many doors you knock,” Bullock says. And in Montana, those doors are often very, very far apart from one another.

Bullock also understands the symbolism of campaign stops. He loves to bring up the story of Barack Obama’s July 4, 2008, visit to Butte, Montana — a hardscrabble, dwindling union town in southwest Montana, once home to the largest copper mine in the country, now home to the largest Superfund site. “At that point, Obama’s already locked up the nomination,” Bullock says. “There was zero advantage for him to go to a place like Butte, Montana. But him being there — it sent a message to all the people off the coasts.” The governor often telegraphs that that’s the sort of campaign he’d run.

“We’ve lost so many rural and working-class voters,” Miller told me. “They perceive that we lost touch with them. But Steve, he hasn’t.” Of course, millions of rural and/or working-class Americans did vote for Democrats — they just weren’t white. In Iowa, though, largely rural counties that hadn’t voted for a Republican in decades swung from voting for Obama in 2008 and 2012 to Trump in 2016. That’s the sort of voter that people like Miller think Bullock can reach — because he has a track record, in two gubernatorial elections, of doing so. And while Bullock has rebuked the Trump administration in many ways, he refuses to villainize the Trump voter. For Bullock, if someone voted for Trump — especially if they voted for him and Trump, or for Obama in 2008 or 2012 and then Trump — it doesn’t mean they’re a horrible person, or a racist, or unredeemable. It means that Democrats weren’t listening and responding to those voters’ concerns. And part of the reason they weren’t listening was because they never showed up to do so.

At a storybook farmhouse near Altoona, Iowa, just outside of Des Moines, Bullock articulated a version of that philosophy at an event for Tim Gannon, a Democrat running for state secretary of agriculture. “These tariffs have reduced the price of my beans by 25%,” the owner of the farm tells Bullock. “We want trade, not 10 million,” the owner of the farm says, referring to the billions in relief Trump had recently promised farmers as he continues to escalate the trade war with China. “And I think the only way we can really get through to Trump on tariffs is at the polls.”

People milled about plastic tables and chairs set out for the event, picking up stickers and dropping off checks to the candidate. Miller was there again, in a red polo shirt with the logo of the attorney general’s office embroidered in the corner, and introduced Bullock from his perch on the wraparound porch with the same line: “He has this ability to connect with people. He does it better than anyone I’ve seen. He listens, he goes out and listens to people in rural areas.”

“There is absolutely no reason that Democrats can’t win in rural parts of Iowa and rural parts of Montana. But we’ve got to believe that first — that we actually do share values.”

And there Bullock was, in a rural area that’s being rapidly swallowed by Des Moines, trying to talk to rural voters over the intensifying buzz of the locusts. “There is absolutely no reason that Democrats can’t win in rural parts of Iowa and rural parts of Montana,” Bullock said. “But we’ve got to believe that first — that we actually do share values. I fundamentally still believe that elections are about people talking to people.”

That belief is why Bullock is tacitly campaigning so early in Iowa — and Michigan, and Wisconsin, and New Hampshire — but Iowa in particular. Most people there don’t know him; the ones who’d heard of him, outside of his previous visits, were college students who’d seen his appearance with YouTube star (and native Montanan) Hank Green — but more will. “Due to the mechanics of Iowa caucuses, you don’t have to be known right away,” Miller explained. “Jimmy Carter is the classic example. He came in, early and often, and had a tremendous upset just by listening to people.” Miller was the first person to liken Bullock’s strategy in Iowa to Carter’s for me, but not the last. “Some people think Bullock running for president is crazy. But I don’t, I really don’t,” said David C.W. Parker, who teaches political science at Montana State University and has published broadly on presidential and Montana politics. “For Democrats, there are so many possibilities — and it’s hard to see them coalescing around someone really quickly. That’s a good thing for Bullock, because he can run a campaign like Jimmy Carter in 1976,” Parker said. “In 1976, there were a lot of heavy hitters. They just jumped in at later times, and were blown away by Carter.”

Plus, Johnson adds, there’s a matter of timing. “Carter came in, post-Watergate, and ran on the promise of clean government,” he said. “And now you’ve got Bullock, in this moment, running on getting money out of politics.” Listen to progressive talking heads and they’ll tell you: Amid an unprecedented investigation into Trump, his administration, his cabinet, and GOP members of Congress who’ve supported him, Democrats should be running, now and in 2020, on an anti-corruption ticket. And that’s precisely what Bullock is attempting to do.

Weeks later, I meet Bullock back in Montana, where he is just returning from the governor’s back-to-school rounds: to the first football game of the year at Montana State, to the opening of a state-funded pre-K program in a town of 700 on the North Dakota border. Today, he’s hopping in the state government’s small plane — a 1979 Beechcraft King Air — to fly to Fort Belknap Reservation, where Bullock will meet the first graduates of a new apprenticeship program being piloted at tribal colleges across the state. He’s back in the casual-candidate jeans, only this time he’s paired them with a suit jacket and a pair of black alligator-skin boots — which he picked up during a visit with the governor of Louisiana, who also took him gator hunting.

In the seat across from Bullock, Jason Smith, Montana’s director of Indian Affairs, gives him a briefing on new issues affecting Native Americans across the state. He lays out the particulars of the grant-funded apprenticeship program, which allows students to train in an occupation — as addiction counselors, or certified nurse assistants, or hazmat technicians — that would allow them to stay on the reservation, where jobs are often scarce, and serve their communities.

On the ground, Bullock is given a warm welcome at Aaniiih Nakoda College, where a handful of staff and apprentices involved with the program have gathered in the newly constructed main building. “The care they’re giving, especially to our elders, not only is it culturally sensitive, but they know the language,” Liz McClain, who’s assisted with the program since 2015, tells Bullock. “It’s something you need to know as governor: Whoever comes through this, they’ve uplifted the health of this reservation.”

“I don’t buy the premise that you have to out-Trump Trump.”

Bullock tells the group that one of the first things his office put together when he was elected was a health improvement plan for the state — including the health of Montana Native Americans, whose life expectancy is 20 years shorter than their non-Native counterparts. “I love how you’ve laid out this process,” Bullock said. “Sometimes you need to look at that granularity.”

The process means getting one person, then two, then a dozen, not only employed, but employed in a way that holistically alters the health of their community for generations to come. Later, as we walk back to the plane, Smith tells Bullock that one of the elders had told him that the buffalo — sacred to the Gros Ventre and the Assiniboine — had come to him in a dream, and told him they needed to give the governor a spirit name. “We need a name for this man,” the buffalo had told him. “He works for the people.”

A visit to a handful of Native American students in one of the most rural areas of the state might seem about as far from running for president as one could imagine. Due to a host of interweaving issues — including distance to polling places, and the fact that, depending on the state, many Natives weren’t allowed to vote until 1965 — voter turnout on reservations is historically low. But the visit is part of the Bullock ethos of showing up, of listening, of paying attention, no matter how rural or urban your population, no matter your political or religious ideology, no matter your inclination to support a campaign, financially or otherwise.

Is showing up and listening enough? Since watching Bullock navigate the state fair, I’d spent three weeks thinking about the larger, harder questions posed by his hypothetical candidacy: the white guy question, of course, but also whether Democrats need someone who can fight Trump’s virality, his scorched-earth domination of the news cycle. “I don’t buy the premise that you have to out-Trump Trump,” Bullock says. “And it’s not what I’m hearing from people on the ground, either — that a candidate needs to be like that.”

There are those who say that catering to the voters who jumped from Obama to Trump in the 2016 election is a fool’s errand: They’re too bigoted, too xenophobic, too deplorable to waste time on. But many of those swing voters were the type who, like many I’ve spoken to in Montana, cast a vote for Bullock for governor and Trump for president not because they liked Trump, but because they could not bring themselves to vote for Hillary Clinton, who they decided had not listened to or spoken to them, their interests, or their hopes for the future of the country.

Many — with good reason — find that logic flawed. But it does suggest that those voters, whether in Montana or Iowa, in Florida or Arizona, are not lost causes for Democratic candidates. It doesn’t have to be a choice between increasing voter turnout or catering to those lost Democrat votes; it can be both.

“Demography suggests that we could win without those Obama–Trump voters,” Bullock explains. “But then you’d get in office, and you’re not going to be able to get stuff done. It has to be about rebuilding our ties to one another, individually, in the community, and nationally. Because if you forget about an entire section of the country, you’re not going to be able to govern. Whoever it is needs to serve everyone.”

For Bullock, “connecting” doesn’t mean avoiding the issues that affect specific, so-called identity politics groups. It doesn’t mean he won’t advocate for better health care on the Fort Belknap Reservation, or for trans kids’ rights in schools, or for women’s reproductive rights. But a candidate can also speak to broader issues — health care, of course, and creating jobs that provide a living wage — while also addressing a new concern for so much of electorate: mending what’s slowly yet startlingly broken down in our country and in our democratic and legislative process over the last few elections.

“Listen, there are people who have been historically locked out of the election process,” he says. “And we have to recognize those historical injustices, and rectify those historical injustices. But we also have to bring the electorate together.”

“That’s really hard to do,” I told him.

“It is,” Bullock replies. “But that just means that we’ve got to do it.” ●