FREEPORT, The Bahamas — After surviving a Category 5 hurricane that left 70,000 people homeless, Bahamians trying to temporarily flee the decimated islands have found themselves trapped in a new disaster: navigating changing US immigration rules.

For nearly a week after Hurricane Dorian hit, Anya Pinder and her children would take their luggage to the edge of the metal fence guarding the Freeport airport runway on Grand Bahama island and sit down in the shaded dirt beneath a tent, hoping to get a flight off the island.

The 36-year-old mother of two breathed a sigh of relief Sunday when her teenage girls, Samaria and Israel, boarded a Baleària Caribbean ferry bound for Florida with their grandfather and nearly 500 others.

Then, her sister, Avery, called to say the teens, along with 119 other passengers, were pulled off the vessel because the ferry company told customers that US Customs and Border Protection wouldn't let in Bahamians without a visa. CBP said the ferry company had failed to adequately prepare their trip with authorities.

"We understand you need a visa in a normal situation, but this isn't a normal situation," Anya told BuzzFeed News as she waited by the airport. "You can't get off the island because our international airport is damaged. People can't get off the island because of a visa. How am I supposed to get a visa? Where do I go for that?"

US policy had previously allowed Bahamians to travel to the US using only a passport and evidence of a clean police record if they were traveling on a flight or ship directly from the Bahamas.

On Monday, the Department of Homeland Security released updated information about visa restrictions, which tightened rules for those arriving by sea.

"Bahamians arriving to the United States by vessel must be in possession of a valid passport AND valid travel visa," it reads.

CBP insists that the rules are simply a clarification of established policies and procedures and that port directors still have the discretion to evaluate people arriving on a case-by-case basis.

But a Baleària Caribbean staffer told BuzzFeed News that the company guidelines for Bahamians coming over to the US for a short visit — before the hurricane it ran ferries between Freeport and Fort Lauderdale multiple times a week on the 2.5-hour trip — said no visa was required.

The staffer was unsure if the policy had changed due to the hurricane, but the company website now says a visa is required. Baleària Caribbean's spokesperson has not responded to BuzzFeed News' request for comment.

A cruise ship carrying 1,100 Bahamians arrived on Saturday in West Palm Beach, Florida, with most on board coming to stay temporarily with family in the US. A spokesperson for Bahamas Paradise Cruise Line said approximately 80% of them had a valid US visa, while the remainder of passengers traveled with their passport and a police report before the restrictions announced Monday.

John Sandweg, former acting general counsel for the Department of Homeland Security and former acting ICE director, said that the statement sent out by CBP officials on Monday night did not contain any new policy or information.

"You do have concerns when you’re dealing with the Caribbean and mass migration at sea. We’ve seen mass migrations at sea from Haiti and Cuba — I think there’d be a lot of caution with anything at sea," he said, referencing whether visa-free travel should be allowed via boat. "People getting on rickety boats — those things can be dangerous."

Even under the Obama administration, he noted, officials would have been “reluctant to do anything to encourage people to take to the water to come to the US."

Sandweg said the administration should, however, be focused on figuring out other mechanisms to help those stranded get to safety.

Still, thousands of Bahamians remain stuck, baffled by the response from the US, a place they can usually visit without drama whenever they want supplies. Most hurricane survivors are just looking for a chance to get off the battered islands and access running water, buy food in supermarkets, or stay with family for a few nights.

"They think we're coming to stay but we're just trying to catch ourselves," Avery Pinder told BuzzFeed News.

Pinder, 28, has been sleeping in a van for the past six days with her boyfriend and 8-year-old daughter. They've parked it in the airport's small lot, still filled with waterlogged cars that no longer run because they're trying to save gas.

It's cramped, stiff, and sticky, but she says they're lucky to have it after what they went through. It took her about a day to get out of her flooded house to get help.

Her daughter survived the pummeling storm surge because she'd been wearing a life jacket. After some of the water receded, Avery swam to her car and used the battery to charge her phone.

"When it got to 1% I posted on Facebook so that people could know we needed help," she said.

And though Avery's house is still standing, it is unlivable, like scores of others that line the abandoned streets: filled with ants, flies, and other bugs, as evidenced by the collection of bumps on her legs.

She wants to leave because she's afraid that her daughter will get sick from the mold and contaminated water. She keeps hearing stories of how her friends and members of her extended family have died, tales of bloated bodies and rumors of cholera.

She's been drinking a lot of water because she's spending more time in the taxing sun but also because it "fills her up" so she won't "feel hungry."

"I'm worried about the food," she explained. "I want to make sure my baby has enough food."

Getting a visa was the last thing she thought she'd need to worry about.

Every day, the Pinder sisters join the crowds standing at the airport in an attempt to snag an empty seat on the spate of small private planes that have been running nonstop delivering food, supplies, and volunteers to Grand Bahama.

The residents, many of them carrying kids and plastic bags full of their only belongings, wait in the balmy sun for hours, pressing their bodies against the fence to try and get the attention of any aid worker on the other side.

They've heard that they don't need a visa to get on a plane (which is true, according to US policy, as long as the plane goes through CBP preclearance in Nassau or Freeport). They've heard pilots are worried about taking people and fearful of getting in trouble with the US government. They've heard if they have a passport and police record, they should be OK. They've heard some groups have connections. They've heard that if you have a medical problem, you have a better chance. They've heard that this is their best shot.

Florence Cooper is one of the lucky ones. Her grandchildren are US citizens, and one of her grandsons has asthma; after waiting for about six hours in the baking parking lot, she was able to get her story to a volunteer with Tampa General Hospital, which had just made a supply run and was flying back with priceless empty seats.

Along with a few others, the 55-year-old and her five grandkids were ushered through the gate as the rest of the crowd huddled closer. Once inside the runway area, their relief and joy were palpable.

"I reached out to a lady in a blue shirt and told her I had a medical emergency, and God is good," the grandmother said.

For pilots, taking evacuees is arduous, said Raymond Morganti, a member of the Family and Patient Advisory Council who is working with Tampa General.

"It's playing games with customs," he said. "You have to take a picture of the Bahamian passport, if they have it, and send it in. And someone at the other end deals with customs, and then you wait until they're cleared."

Although he and his organization have made about six flights, this is the first time they were able to take a family back, he said, and it's because only one member wasn't a US citizen.

Like many others, Morganti wonders why US officials aren't on the ground.

"They should set up a US customs tent here and clear the people like any airline would do, but they're not going to do that," he said.

He then paused for a phone call: "Yep, we got them. Let's make sure we have some snacks and stuff to love up on 'em when we get back. We're just waiting on customs. It's taking a long time."

Experts in the US criticized the Trump administration's tightening of visa restrictions.

"These are people whose homes and possession have been destroyed or lost," said Harold Hongju Koh, a former State Department legal adviser and current Yale professor.

"In ordinary times, you would expect our government’s humanitarian response to be a general grant of temporary protected status (TPS) for affected Bahamians, not this obsessive focus on having 'the right papers' which fails to acknowledge the emergency nature of the humanitarian crisis that we have all just watched unfold," he said.

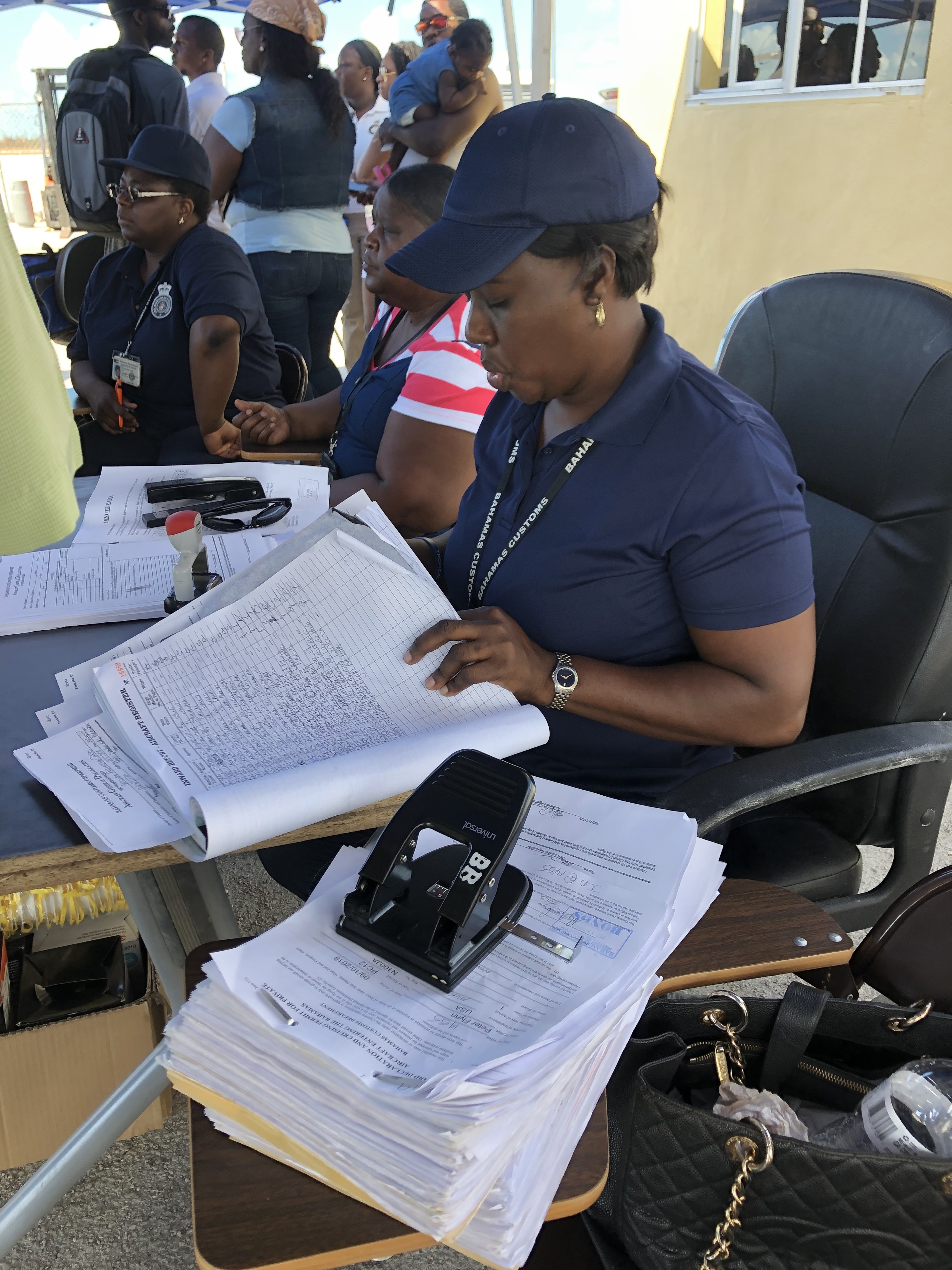

Instead, Bahamian immigration and customs officials on the ground are baffled about how their fellow citizens can evacuate to the US. Information seems to be contradictory and ever-changing.

"It's very chaotic," said Rodney Wildgoose, a senior Bahamas immigration officer at Freeport airport.

Filling out ream after ream of paperwork, about five weary Bahamian immigration and customs officials say their job is only to check in those who have arrived, not to help issue visas or check the documents of residents trying to evacuate. There's been no real communication with US CBP here, Wildgoose said, explaining that different US ports are accepting survivors with a range of documentation.

"Some pilots are taking them to ports that don't need visas," Wildgoose said, gesturing to the crowd on the other side of the fence. "Most ports are requiring a US visa or just a valid police record or passport."

"They told us that if they have a valid police record, it's fine, they have loosened restrictions."

CBP port directors may have discretion to accept hurricane survivors, but that doesn't mean the Pinders can get easily get on a boat or plane.

Although they're frustrated and drained, they understand US officials' concern. They've seen President Trump talking about potential gang members and drug dealers, but they're not trying to enter the country illegally or stay once they get there. They only want a break, some air conditioning, a shower, a hot meal, and a chance to breathe. After that, they want to go home and rebuild.

"We want to come back because there's no place like here," said Avery, "but you can't even grieve properly because there's too much going on right now."

Amber Jamieson, Hamed Aleaziz, and Adolfo Flores contributed reporting to this story.