The fight over the legality of Donald Trump’s appointment of acting attorney general Matthew Whitaker began with the death of J. Edgar Hoover nearly five decades ago. And it won’t necessarily end with the expected nomination of William P. Barr to become the next attorney general.

After Hoover died, Democrats began to fear that, by naming a loyalist to one of the nation’s top law enforcement roles in an acting capacity, then-president Richard Nixon would be able to receive information about and potentially influence an ongoing investigation of the president and his allies without even needing to seek Senate confirmation of his appointee.

The executive branch defended the appointment, beginning a 25-year fight that led to Congress pressing forward legislation in two different decades aimed at restricting who could be appointed to acting positions and how long they could serve.

In 1998, however, the Clinton administration and allies on Capitol Hill pushed back on the second bill — fighting for more flexibility in whom presidents could appoint and getting a legislative change that last month was used by the Trump administration in making Whitaker the acting attorney general.

So, how did we get there?

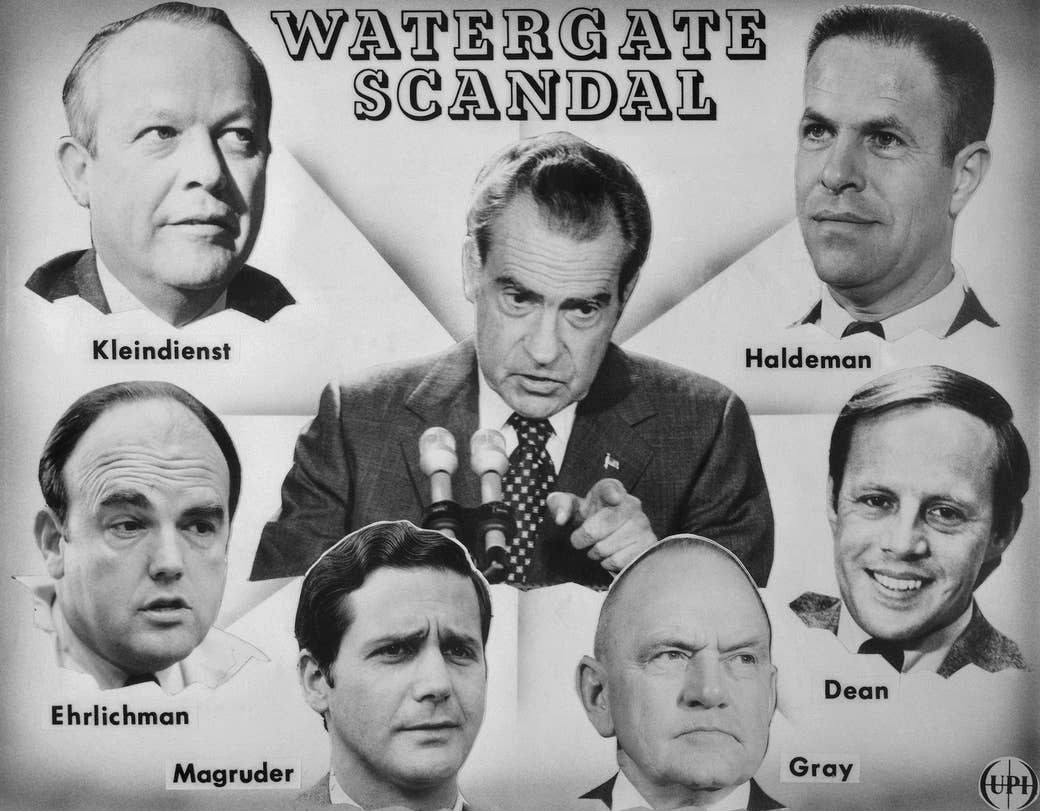

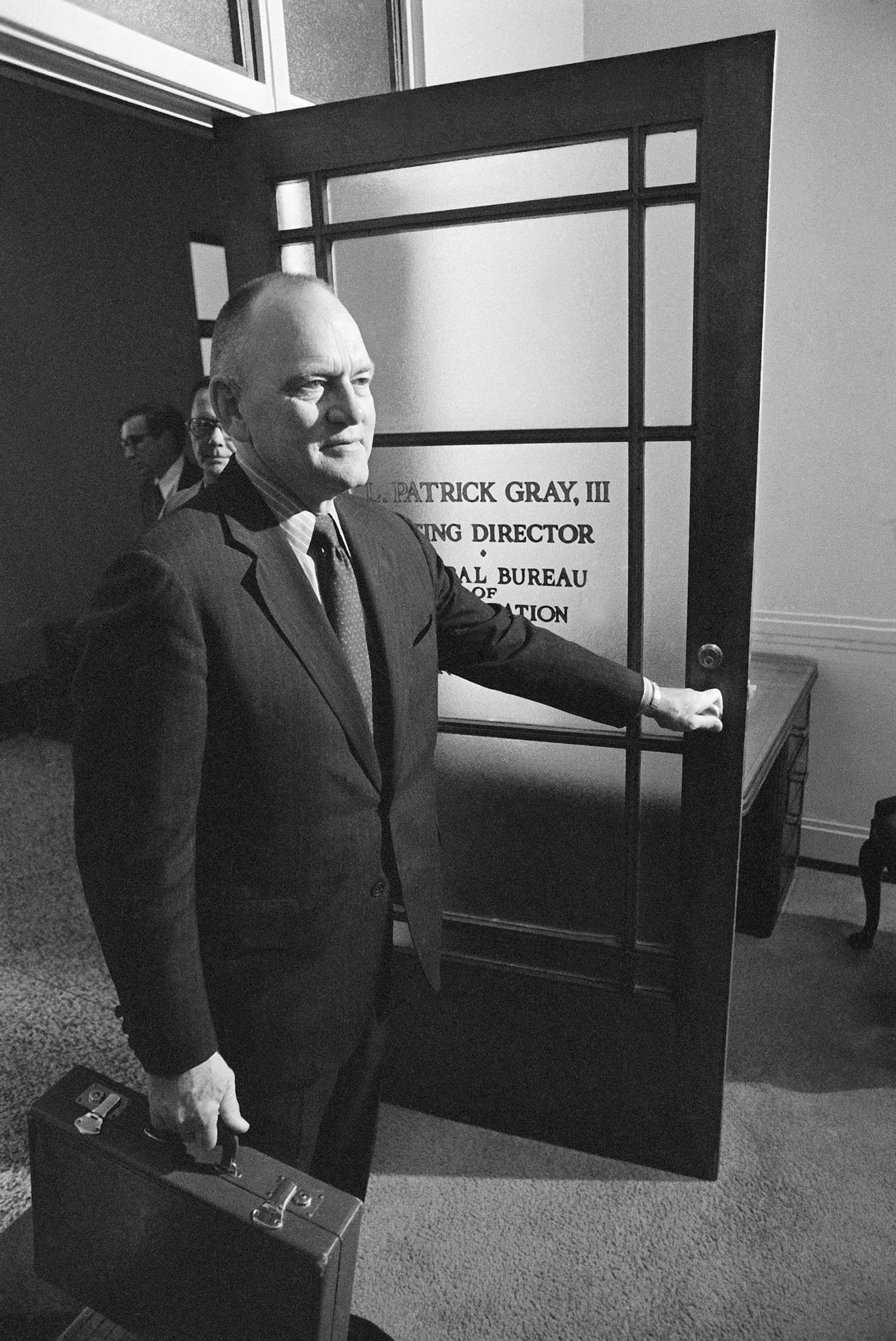

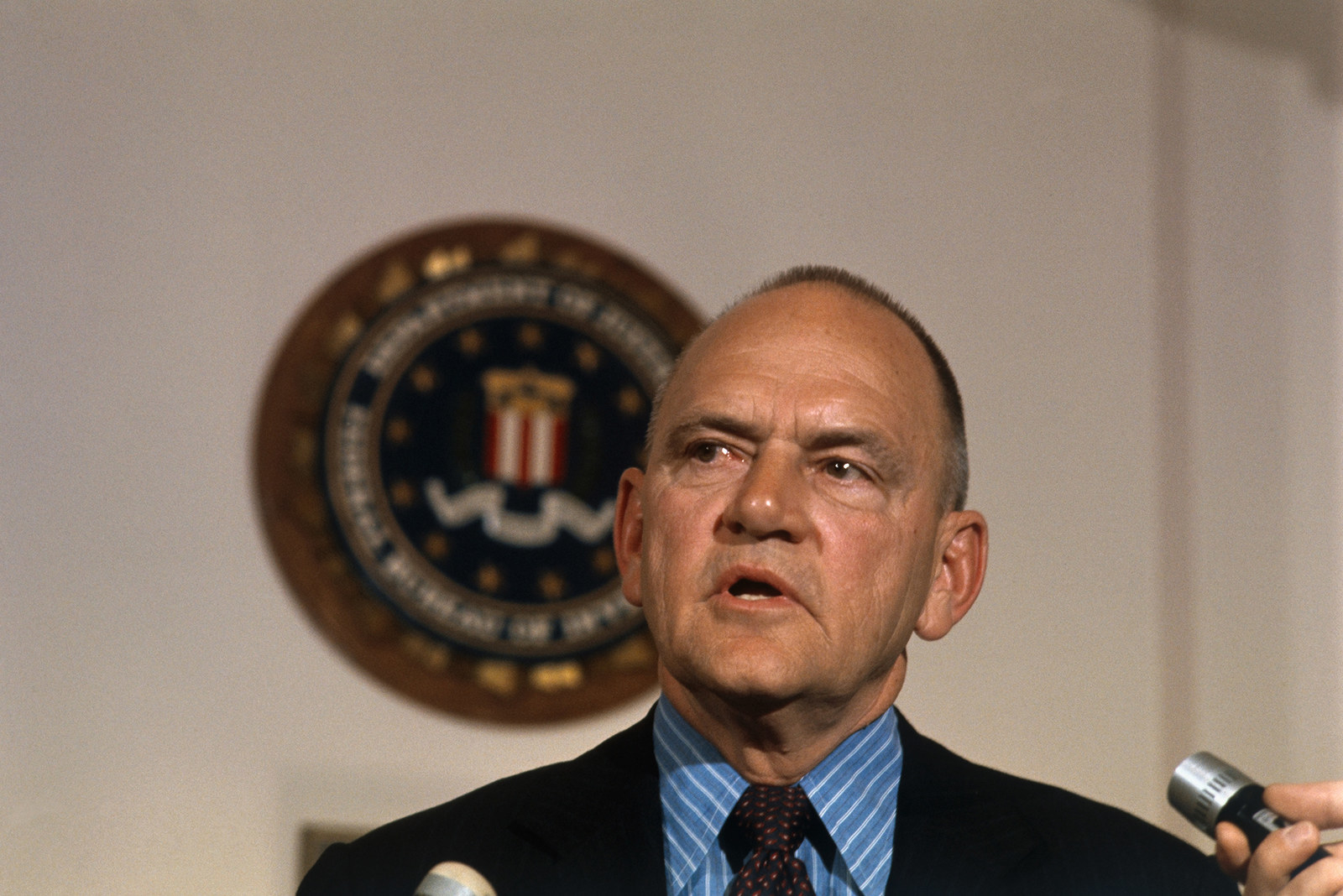

The year was 1972, Nixon was president, and he was running for reelection. In the midst of that, Hoover, the first and longtime director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, died. Although Congress had passed a law requiring that the next director be confirmed by the Senate, Nixon named L. Patrick Gray, a loyal supporter who’d first worked for Nixon when he’d been vice president, to be acting FBI director in the meantime.

Six weeks later, the Watergate break-in that eventually would bring down Nixon took place. Gray oversaw the FBI's investigation from his acting FBI director perch, all the while maintaining close ties to the White House. Gray’s acting appointment, though, would end in damning testimony by Gray against the White House — and Gray’s eventual failed nomination to become the permanent director.

This isn’t really a story about Watergate, though. (It is, a little.) It’s about the fight that has percolated ever since over presidents’ acting appointments, how Congress has responded to those appointments, and how the resulting changes in the law made Whitaker’s appointment possible — and led to the legal challenges to the appointment.

Nixon’s appointment of Gray as acting FBI director — and his service in that position for nearly a year — raised questions about a president's ability to appoint key officials without Senate confirmation that have vexed government lawyers, White House administrations, and lawmakers since. While the Justice Department defended Gray’s appointment as a legal one, lawmakers pushed back and another officeholder — the comptroller general — disagreed, beginning the first of several such fights over the past half century.

That fight continues. Currently, there is litigation in courts around the country — all the way up to the Supreme Court — challenging whether Whitaker is properly in his post. And Whitaker is likely to remain acting attorney general until Trump's nominee, Barr, is confirmed by the Senate — something that wouldn’t happen (if he is confirmed) until sometime in 2019.

The Appointments Clause of the Constitution controls this debate. The clause gives the president the power to nominate “officers of the United States” but requires “the advice and consent of the Senate” for those officers to take office. But it also states that “the Congress may by law vest the appointment of such inferior officers, as they think proper, in the president alone, in the courts of law, or in the heads of departments.” In short, so-called principal officers must receive Senate confirmation, while inferior officers may not require it, if Congress permits.

Some of the talk about the legality of Whitaker’s appointment circles around the question of whether an "acting" officer like Whitaker is an inferior or principal officer. The debate reaches all the way back to a law passed when George Washington was president and was addressed in an 1898 Supreme Court case, but has left open questions debated today.

The modern fight over nominations, however, has largely been a fight between the executive and legislative branches — and it began with Gray but reached a fever pitch over a Clinton appointee to run the Department of Justice's Civil Rights Division.

Congressional leaders decided to take action — proposing legislation in 1998 that would restrict when and for how long the president could appoint acting officers and who they could be. If someone served as an acting officer who was not authorized to do so, the bill also would prevent later-serving officers from ratifying any actions taken by that person.

“When a vacancy occurs in [a Senate-confirmed] office, it is important to establish a process that permits the routine operation of the government to continue, but that will not allow the evasion of the Senate's constitutional authority to advise and consent to nominations,” the late senator Fred Thompson, a Tennessee Republican, said in introducing the legislation.

The Clinton administration pushed back with talk of a veto, and the administration and Senate allies made requests for changes to the bill — including to the proposed limits on whom the president could appoint as acting officers. Ultimately, they succeeded in getting some of those changes, and President Bill Clinton signed the Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998 into law in October of that year as part of an appropriations bill.

One of the changes made to the bill allowed the president to name certain high-ranking staff in a department to serve as the acting officer if they’d worked in the department for three months in the prior year.

“All of this was driven by pragmatism in the sense that the president had an obligation to ensure that the business of the government went forward, and he had to do what he had to do to accomplish that,” Robert Weiner, a former Clinton White House lawyer, said of the White House’s efforts in a recent interview with BuzzFeed News. “It was really a rule of necessity.”

Twenty years later, Trump and the Justice Department would use that language in the vacancies law as the legal justification for Whitaker’s appointment.

And Weiner, now in private practice, is working on a legal effort to challenge the appointment.

L. Patrick Gray had known Nixon since 1947. He'd worked for him when Nixon was vice president and unsuccessfully sought the presidency in 1960. When Nixon won the presidency in 1968, Gray, who was practicing law in Connecticut at the time, joined the administration, first in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Later, he was nominated by Nixon and confirmed by the Senate to serve as the assistant attorney general in charge of the Justice Department’s Civil Division.

When Hoover died in May 1972, Nixon chose Gray to take over as the acting head of the agency that Hoover had run since its inception. Nixon did not, however, initially nominate Gray — or anyone else — to take on the job permanently.

On June 17, the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate complex was broken into, the FBI was immediately in the middle of the investigation, and questions about the agency’s handling of the investigation began soon after.

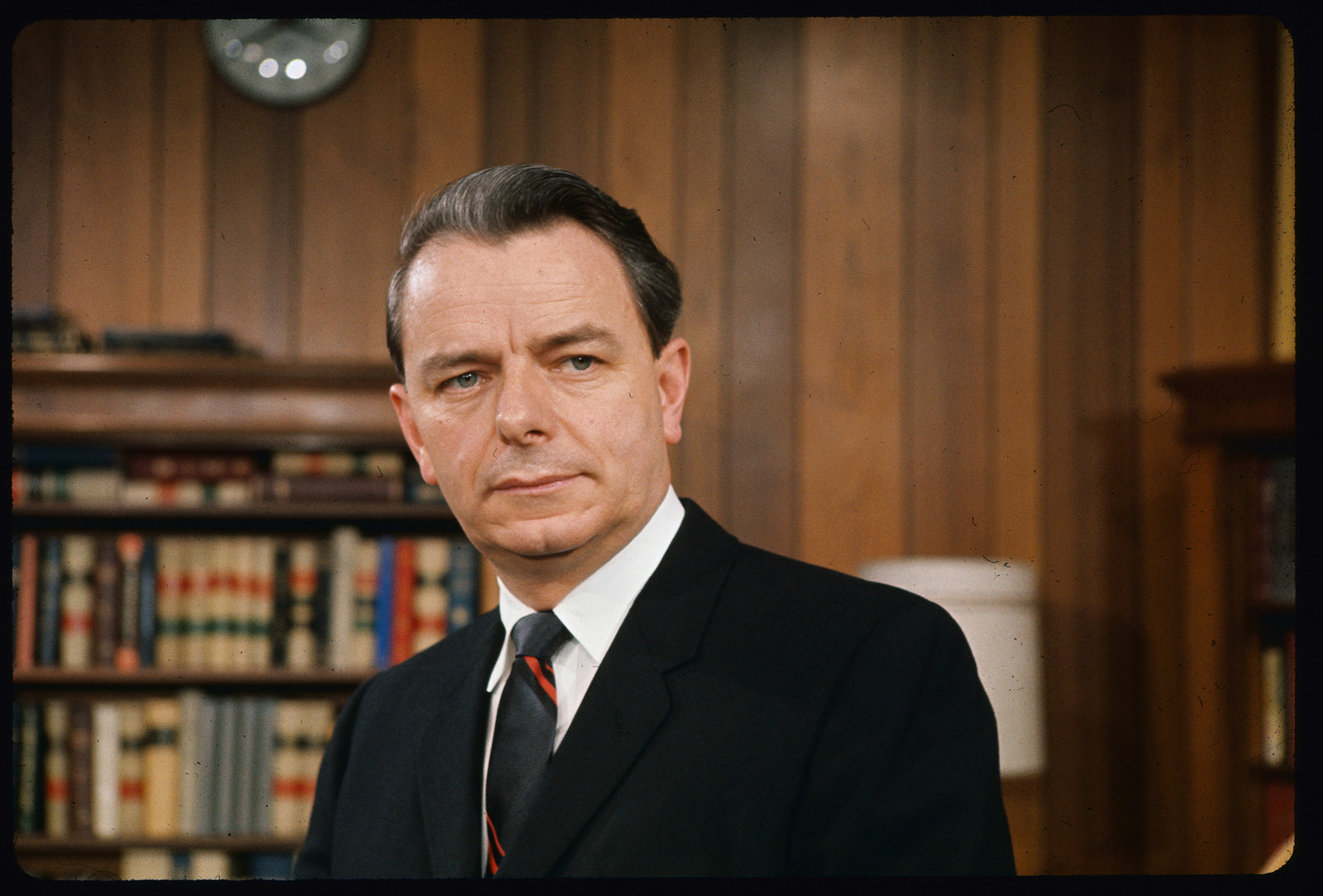

Days later — and 50 days after Hoover’s death — the late Wisconsin senator William Proxmire raised a question about the legality of Gray’s continued service as acting FBI director. He asked the comptroller general, as the head of the General Accounting Office (now the Government Accountability Office) — the legislative branch's office that audits the government — to examine whether a federal law aimed at limiting such “acting” appointments applied to Gray.

Gray continued to run the FBI as the investigation into the Watergate break-in continued to unfold within the agency and in stories about the Nixon campaign’s tactics that took over the pages of the Washington Post.

On Jan. 10, 1973 — more than eight months after Gray took his post — the Justice Department announced that a law aimed at limiting so-called acting officers to serving in roles for more than a month didn’t apply to Justice Department appointments. Instead, the department argued that broad authority under which the attorney general can delegate functions of the office to others made it possible for “acting” officers in the DOJ — which would include the FBI — to serve for as long as the attorney general desired.

The comptroller general pushed back the next month. Responding to Proxmire’s letter, the comptroller general asserted that the DOJ-specific law was not aimed at addressing vacancies at all. Instead, the comptroller general concluded that the law limiting “acting” officers — the Vacancies Act — did control. Under that interpretation, Gray could only serve as acting FBI director for 30 days.

In the meantime, however, Nixon nominated Gray for the post formally, putting off the issue for the time being.

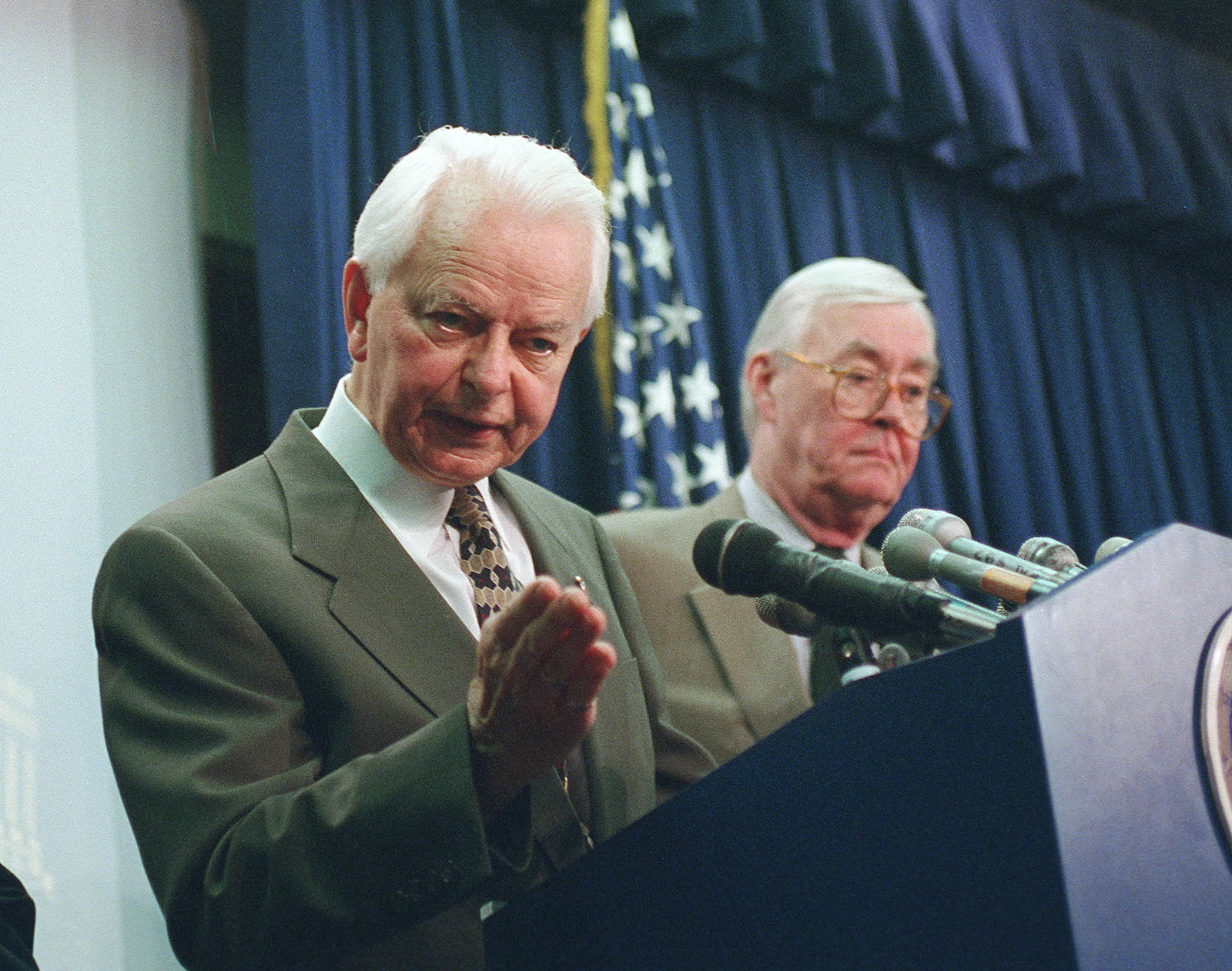

For Gray, the nomination was the high point. From the first day of his confirmation hearings, the nomination got bogged down by questions about Gray’s partisan activities while serving as the acting head of the FBI during Nixon’s reelection campaign — questions raised at one point by a second-term senator from West Virginia who was one of the two most-junior Democratic members of the committee at the time: Sen. Robert Byrd. As the hearings continued, Gray eventually would provide significant, damning testimony about his communications with White House aides about the Watergate investigation — leading Nixon adviser John Ehrlichman to famously say that the president should let Gray’s nomination “twist slowly, slowly in the wind.”

By that point, Gray’s nomination was doomed. While his testimony about his White House interactions angered the White House, it also lost him significant Senate support — and the revelation that he had destroyed documents provided to him by White House officials ended things altogether. Byrd planned a procedural vote to sink the nomination, but the move became unnecessary when Gray had the White House withdraw his nomination.

Nonetheless, Gray’s appointment and service for nearly a year as the acting FBI director had begun a 25-year fight over whether departments and agencies could do an end run around the Vacancies Act restriction that acting officers serve only 30 days by pointing to the entities’ general foundational statutory authority as a basis for, effectively, ignoring the Vacancies Act.

This fight — which ultimately centered around congressional leaders angered at what they saw as presidential efforts to ignore the constitutional role of the Senate in the appointment process — continued into the 1980s, with Proxmire again writing to the comptroller general, this time in response to a series of acting appointments under the Reagan administration within the Department of Health and Human Services.

Noting that the 1973 opinion regarding Gray led Nixon to nominate Gray for the post rather than having him continue on solely as “acting” FBI director, the comptroller general in 1986 wrote that “our more recent decisions finding various Executive Branch officers serving in violation of the Vacancies Act have had less than the desired salutory effect.”

He continued: “In fact, there now seems to be a discernible pattern for Executive Branch agencies to take exception to our decisions on Vacancies Act questions and, supported by the Department of Justice, to ignore the holdings of these decisions.”

That dispute led Congress to amend the law to clarify a court ruling that limited which executive branch entities were even potentially covered by the law and to allow an acting officer to serve for 120 days — instead of just 30. The amendments aimed to make clear that the Vacancies Act should control all such “acting” appointments.

It didn’t work.

The Justice Department soon issued an Office of Legal Counsel opinion regarding the 1988 amendments, noting that the changes didn’t actually require changes to DOJ’s long-standing view that general statutes could be used to authorize acting appointments within a department. “We do not believe ... that a congressional committee can alter the proper construction of a statute through subsequent legislative history,” the opinion noted. (The OLC lawyer who wrote that opinion: William P. Barr, Trump's pick to be the next attorney general.)

The acting appointments kept happening, and they kept happening more often and lasting for longer periods of time.

It continued until the Senate wouldn’t act on Bill Lann Lee’s nomination to run the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. In response, President Bill Clinton decided to name Lee the acting assistant attorney general for the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division.

This time, more dramatic changes would be sought.

On July 21, 1997, Clinton nominated Lee — who had previously worked for the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund — to run the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. Like an earlier nominee for the post, Lani Guinier, Lee faced opposition over his support for affirmative action, as well as his views on school desegregation. This time, however, Clinton didn’t back down as he had when he withdrew Guinier’s nomination in 1993.

When the Senate Judiciary Committee did not move Lee’s nomination forward and the Senate returned the nomination as the session of Congress came to a close, Clinton decided to use the Justice Department’s long-standing position on the non-applicability of the Vacancies Act to acting positions to install Lee anyway.

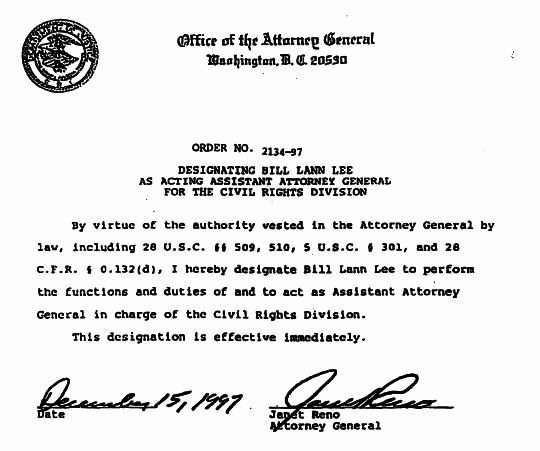

On Dec. 15, 1997, Attorney General Janet Reno designated Lee the acting assistant attorney general for the Civil Rights Division. And while Clinton continued to renominate Lee to serve as the assistant attorney general, the Senate never took up the nomination.

The Senate did, however, take action against Clinton — and future administrations — in response to the acting appointment. It wasn’t only Republicans angered by the Clinton–Reno move: Robert Byrd — who’d pushed back against Gray’s nomination in 1973 and was now serving in his seventh term in the Senate — helped lead the fight.

Conservatives quickly took aim at the appointment, and Byrd joined them. He had advised Reno against making the appointment in the first place, and when she did so anyway, he and others began looking for a legislative change. The Senate Judiciary Committee held hearings over compliance issues with the Vacancies Act in March of 1998. Byrd and Sens. Strom Thurmond and Trent Lott introduced early bills to address aspects of the Senate’s concerns. Working with Sen. Fred Thompson, who was the chair of the committee, the trio of senators and Sen. William Roth prepared more robust legislation aimed at tightening Senate control over the executive branch’s 25-year end run.

For Byrd, on vacancies and appointment issues, "It was not a D–R partisanship, it was an executive-versus-legislative partisanship,” a former Byrd staffer told BuzzFeed News in an interview.

“So, he told me … ‘You get with Thompson’s guys, and you work out the tightest thing you can come up with.’ So, we started [putting together legislation],” the former staffer said. “[Byrd’]s attitude was, ‘If you can’t get a nomination up to the Hill in four months, then to hell with you, Mr. President.’”

The five senators, led by Thompson, introduced the Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998 on June 16, 1998 — six months after Clinton and Reno’s move, and with Lee still in the acting role.

In introducing the bill, Thompson noted the Justice Department’s 15-year-old position that the Vacancies Act, in effect, did not apply to acting appointments within the department — and the expansion of that interpretation to other departments under Reagan. As to the Clinton administration, Thompson went on to say that the Vacancies Act was more or less completely ignored.

“Each department has at least one temporary officer who has served more than 120 days before any nomination was sent to the Senate,” Thompson said. “Of the 320 executive department advise and consent positions, 64 are held by temporary officials. Of the 64, 43 have served longer than 120 days before any nomination was submitted to the Congress.” Of note, Thompson highlighted that the Census Bureau was being run by an acting director who “is neither the first assistant nor a person who has been confirmed by the Senate, a mind-boggling violation of the law.”

The bill aimed to end the long-standing DOJ end run around the Vacancies Act by declaring, explicitly, that “general authority” statutes did not authorize department heads to name acting officers, let alone with no time limitations. The bill specified, instead, that in the event of a vacancy the first assistant “shall perform the functions and duties of the office temporarily in an acting capacity” or the president could direct that the vacancy be filled by a person who has been confirmed to a position for which Senate confirmation was required. In either case, the acting appointment could only last for 150 days — a one-month increase over the 1988 increase to 120 days. Additional time was to be given for those appointed to an acting role during a presidential transition.

The bill also responded to an appeals court ruling in which the court held that the existing vacancies law allowed for a president to name a new acting director to a position that had last been filled by a Senate-confirmed individual four years earlier. In the case, which involved the Office of Thrift Supervision, the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit also found that a validly appointed officer could “ratify” earlier actions taken by a person whose appointment could be challenged as being invalid.

As Thompson said in introducing the FVRA, “Overruling several portions of that decision have become a priority.” The new legislation would start the clock running for acting appointments on the day the vacancy occurred and detailed that an action taken by a person serving in an acting position illegally “has no force and effect” and “may not be ratified.”

A month later, the bill was reported to the full Senate with minor changes, along with a Senate report that declared that “Congress was not successful” through the 1988 amendments “in gaining the Justice Department's agreement that its advice and consent positions are subject to the Vacancies Act.”

Congressional action was needed, it stated, to enforce the “constitutional mandate that persons serving in advice and consent positions do so through the Senate's approval of such service.”

That same morning, however, the White House was preparing its own response.

In a July 15 email, Stephen Elmore in the Office of Management and Budget's Legislative Reference Division alerted several White House staffers to the fact that “today … was the deadline” for comments on a letter regarding the bill. (Among the recipients was Elena Kagan, who then worked in the Clinton White House’s Domestic Policy Council. The Supreme Court nomination of Kagan, now a justice, led to the email being produced by the Clinton Presidential Library in 2010 and be publicly available today.) A week later, a further draft of the letter — to be sent to Lott, the Senate majority leader, and Sen. Tom Daschle, the minority leader, from White House chief of staff Erskine Bowles — was circulated.

“The Administration cannot support this legislation in its present form,” the draft stated. “First, the legislation too narrowly limits who can serve in an ‘acting’ capacity. … This legislation could actually prohibit a President or agency head from appointing the most qualified person to the acting position. For example, if the most qualified and appropriate person to serve in an acting capacity is a career employee with vast experience at the agency, then this bill would prevent the career employee from acting in the position.” A finalized version of the letter was sent on July 28.

When the bill came up for floor consideration, the administration formalized the Bowles letter, issuing a Statement of Administration Policy that referenced the Bowles’ letter, reiterated the concern that the bill would “too narrowly limit who can serve in an ‘acting’ capacity,” and stated that “the President’s senior advisers would recommend that he veto the bill” if passed as it was reported to the full Senate.

The statement was developed by Elmore, according to a Sept. 23 email, and Robert Weiner from the White House counsel’s office and Roger Ballentine from White House legislative affairs “concur[red] with the position,” per the email.

Over in the Senate, Clinton had allies. Despite Byrd’s strong backing for the bill, Democrats pushed back against the constraints the legislation would have place on Clinton’s appointment powers.

On Sept. 28, the administration and its allies were successful.

“There was a cloture vote on that bill, and it failed,” a former Republican staffer who had worked on the bill told BuzzFeed News. “And it failed because [Sen. Carl] Levin and [Sen. Richard] Durbin felt it tied the president’s hands too much as to who could be an acting officer.”

The FVRA only received 53 of the needed 60 votes to end debate and force a vote on the legislation.

In less than a month, though, the bill would become law — but not before some significant changes, that addressed some of the administration’s concerns, would be made.

An omnibus appropriations bill passed in both chambers in July had some differences to be worked out, so a conference committee was established to come up with a bill that both chambers could agree on.

They met just four days after the supporters of vacancies reform couldn’t get the 60 votes for cloture, and Byrd was one of the senators on the conference committee. Given that the House and Senate were both run by the Republicans — meaning they already had a majority of the seats on the committee — the presence of Byrd as one of the Democrats meant that they had votes to spare when someone sought to insert the Federal Vacancies Reform Act into the appropriations bill.

Byrd put the vacancies bill into the appropriations bill, the former Republican staffer said, but by time it was reported to the floor it was different in several respects from the bill that had been on the Senate floor in September.

The key change relevant to today’s dispute about Whitaker’s appointment addressed the administration’s concerns about the narrow limits on who could be appointed. A new section was added, specifying that in addition to the first assistant or a Senate-confirmed presidential appointee being able to be acting officers, a wide swath of senior government officials within the agency also could fill in if the president so chose.

Specifically, the bill provided that the president could “direct an officer or employee of such Executive agency to perform the functions and duties of the vacant office temporarily in an acting capacity,” if the person worked in the agency “for not less than 90 days” in the prior year and the person’s pay rate is “equal to or greater than the minimum rate of pay payable for a position at GS–15 of the General Schedule.”

The language goes even further than the administration’s concerns would have required, and it is not clear from a thorough review of available documentation and interviews with several people involved in Hill and White House negotiations over the legislation who actually drafted the change.

Weiner — who worked on the legislation in the White House counsel’s office and is now a partner at Arnold & Porter — told BuzzFeed News that he didn’t recall the specifics of who devised the particular language, but he did acknowledge the White House’s more general involvement in crafting a compromise. (He also acknowledged working on a matter relating to Whitaker’s appointment, although he did not, at the time, provide any further information on what that matter was.)

“I remember we were scrambling to try to find language that they could live with and we could live with, and it was — we got all sorts of alternatives — and it was very complicated, and I had to spend a lot of time walking through it with people because there were all these permutations,” Weiner said.

At the other side of the legislation, a former Byrd staffer told BuzzFeed News that the language did not come from Byrd’s office.

"I cannot tell you where that language came from,” the former staffer said. “I can tell you where it didn’t come from, and that is Sen. Byrd. And I’m pretty sure it didn’t come from Sen. Thompson."

After the Lee nomination, the former staffer continued, "Byrd went apoplectic, and Thompson was with him, so I doubt seriously that that language about the GS-15 came from Thompson’s office, and I can tell you factually, it did not come from Byrd."

The former Republican staffer said he thought it likely that they would have negotiated the language with the Democrats who had been leading the opposition to the bill. The Senate report included language from five Democrats, endorsed by two others, that would fit the bill: "One possible alternative would be to allow a third category

of individuals to temporarily fill positions, such as a qualified individuals who have worked within the agency in which the vacancy occurs for a minimum number of days and who are of a minimum grade level."

Of the language, the former Republican staffer said, “That came in response to not getting the 60 votes. We negotiated that with — I’m sure we negotiated that with the Durbin and Levin people, but I don’t have a clear — this was 20 years ago — I don’t have a clear recollection of how that was done precisely, but that’s what happened.”

Neither Levin, who left the Senate in 2015, nor staff for Durbin responded to requests for comment. (Although not mentioned by the Republican staffer, evidence from the Senate report and White House emails also suggest that Sen. John Glenn played a key role in opposition. He left the Senate months after the legislation was passed and died in 2016.) Levin, however, acknowledged the change in a floor speech the day of the final Senate vote.

"The legislation allows first assistants, other Senate-confirmed officials, and other qualified high-level agency employees to serve as acting officials," he said at one point in a speech that thanked Byrd and Thurmond for their work in having "identified a serious problem" with the vacancies law and, after proposing the FVRA, for having "worked diligently to resolve the various conflicts over this legislation."

Thompson also referenced the change, noting the new provision and saying, "Concerns had been raised that, particularly early in a presidential administration, there will sometimes be vacancies in first assistant positions, and that there will not be a large number of Senate-confirmed officers in the government. In addition, concerns were raised about designating too many Senate-confirmed persons from other offices to serve as acting officers in additional positions."

In Byrd's extensive comments that day, however, he did not mention the change.

Others involved in the process told BuzzFeed News that they did not recall the specifics of the change, due either to the time elapsed or to the fact that they say they were not involved in the change. Some did not respond to requests to discuss the language.

Another change addressed the overarching concern expressed by the Clinton administration about the effect of the time limitations. Those concerns were eased by adding another 60 days to the time limit on the “acting” appointment — all the way up to 210 days. (The additional time provided for in the original bill sent to the full Senate for a presidential transition, 90 days, would mean an acting appointee at the start of a new administration would be given roughly 10 months to serve in an acting role.)

The new version of the bill also eliminated a provision that stated that “[w]ith respect to the office of the Attorney General of the United States, the provisions of section 508 of title 28 shall be applicable.” Section 508 sets forth a particular order of succession for the Department of Justice that operates separately from the vacancies law. The prior Vacancies Act similarly exempted the attorney general's office from the provision allowing the president to appoint an acting officer, so the initial FVRA language appeared to be intended to keep that exemption in place. The October changes eliminated that explicit exemption.

Finally, and somewhat related, a provision was altered that referred to the law’s “application” — this is the part that explicitly states that “general authority” statutes cannot be relied upon as a grant of authority to make acting appointments. The conference committee’s version stated that the vacancies law will be the “exclusive means for temporarily authorizing an acting official to perform the functions and duties of any office of an Executive agency” — unless another law “expressly” allows for acting officer appointment or designates someone to be an acting officer.

The day after the conference report was filed, the House agreed to the changed legislation. The next day, Oct. 21, 1998, the Senate agreed as well and President Bill Clinton signed the Federal Vacancies Reform Act, as amended in the appropriations bill, into law.

And so it proceeded, with presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama exercising their nomination and appointment authority under the new law.

The law, however, did not end the disputes.

In the Bush administration, questions were raised about the scope of the president’s power in light of both the Appointments Clause and the Vacancies Reform Act. The first related to Bush’s sought designation of an acting director of the Office of Management and Budget. At that time, and relevant to today, DOJ’s Office of Legal Counsel advised that Bush could do so because an “acting” director is not a “principal” officer — who must go through Senate confirmation, under the Appointments Clause — even though the position of OMB director is.

Later, a question arose as to what the “exclusivity” provision meant when Bush sought to appoint an acting attorney general using the Vacancies Reform Act rather than adhering to the DOJ-specific succession law. DOJ, again, said Bush could do so, finding that the law provided for the exclusive use of the vacancies law in most situations. When there was an alternative statute, like the DOJ-specific one, OLC advised that it did not replace the vacancies law. “The Vacancies Reform Act nowhere says that, if another statute remains in effect, the Vacancies Reform Act may not be used,” Steven Bradbury wrote.

Under the Obama administration, a challenge arose over Obama naming an acting general counsel to the National Labor Relations Board. The dispute centered around whether the limits on service of a person in an acting position when nominated for that position applied only to first assistants in an acting position or to anyone named under the FVRA. The Supreme Court eventually heard the case, and said the limits applied to “anyone performing acting service under the FVRA.” (Notably, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a concurring opinion in the case, raising an issue that he said "raised grave constitutional concerns" and would eventually need to be addressed by the court: whether the vacancies law allows the president "to appoint principal officers without the advice and consent of the Senate." Thomas wrote that he believed it does, which would violate the Appointments Clause.)

Then came Trump. Several non-Senate-confirmed people have been named to secretary-level acting positions — including at the departments of Energy, Education, Health and Human Services, and Veterans Affairs — during the past two years. There was an unsuccessful challenge to Trump’s authority to appoint his Senate-confirmed head of OMB, Mick Mulvaney, as acting head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Nonetheless, it was Whitaker’s appointment as acting attorney general that caused the most high-profile opposition. Trump had been angry for more than a year at Attorney General Jeff Sessions for his decision to recuse himself from the Russia investigation, and that backdrop — and the specter of a Trump loyalist who had expressed dissatisfaction with special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation potentially overseeing that investigation — quickly led to legal challenges.

Some of the challenges have focused only on the constitutional question of whether Whitaker can serve in the role under the Appointments Clause. Others, including one matter pending at the Supreme Court, have challenged Trump’s use of the vacancies law at all — asserting that the DOJ-specific statute, under which Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein would be the acting attorney general, should control.

The Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel defended the president’s decision, writing in a 20-page memorandum that “[a]lthough an Attorney General is a principal officer requiring Senate confirmation, someone who temporarily performs his duties is not.” The memo details times throughout the country’s history when the president named non-Senate-confirmed people to acting positions, the legislative history of authorizing non-Senate-confirmed individuals to be able to be named to acting positions, and courts’ rulings — including the 1898 Supreme Court case — allowing for non-Senate-confirmed individuals to be named to acting positions.

Those challenging the appointment by saying the laws require the DOJ-specific statute to control have backing from Morton Rosenberg, a now-retired longtime analyst at the Congressional Research Service who had conducted significant research on the vacancies laws during his time at CRS. In a filing at the Supreme Court, Rosenberg argued that Whitaker’s appointment is invalid: “Rod Rosenstein is the Acting Attorney General.” Regarding the 1998 law, he argued that the removal of the attorney general–specific language from the bill was intended to ensure that all existing laws regarding succession from any agencies, and not just DOJ, would still have force — a point that he claimed was reinforced by the language in the “exclusivity” section of the law.

The most persuasive constitutional argument by those challenging the appointment is that the underlying logic of cases allowing for prior acting appointments of non-Senate-confirmed individuals to positions that otherwise would require Senate confirmation is exigency — a need to fill the position — and the lack of another person who had been confirmed by the Senate to do so. They argue in effect that, in those situations, two constitutional commands — the Appointments Clause and the requirement that the president “take care” to see that the law is “faithfully executed” — had come into conflict and so a compromise allowing the acting appointment was OK’d.

“With regard to the President’s designation of Mr. Whitaker, however, there are no such special conditions, there is no exigency, and there is no threat to the President’s ‘take care’ obligation,” one set of lawyers wrote in opposing Whitaker’s appointment. “The President talked for months about firing Mr. Sessions, and it was widely reported that he would do so just after the midterm election. The reports proved right.”

One of the lawyers making that argument: Robert Weiner, the Clinton White House lawyer who helped work on the compromise language in 1998. ●