MARIUPOL, Ukraine — If you’re lucky enough to be within microphone-reach of Volodymyr Zelensky these days and to see the Ukrainian president take a question about Donald Trump, you’ll witness some impressive facial gymnastics. His eyes and brows will narrow as he leans in to hear the question. Then, upon registering it, his face will tense up, his eyes will widen in dread and he’ll purse his lips. Finally, as you push for a straight answer, he’ll screw up his eyes and throw back his head, as if to beg the heavens to rid the sky of the Trump-shaped cloud that has cast a shadow over his country and nascent presidency.

It’s a move he’s repeated time and again over the past month and a half, as the 41-year-old president has performed the political equivalent of a Simone Biles floor routine to escape his unexpected and unwelcome role in the frenzied political drama unfolding in Washington that may very well lead to Trump’s impeachment.

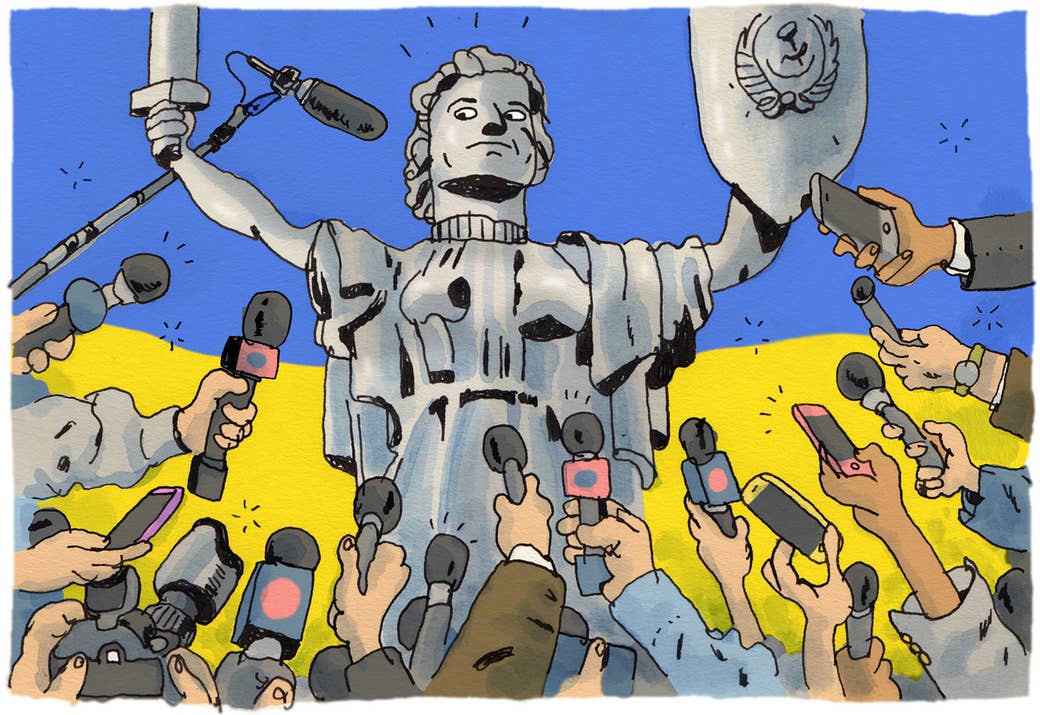

Zelensky, a former stand-up performer who’s used to being onstage, admitted during a marathon news conference last month that he “really wanted to be world-famous, but not because of a situation like this.” He’s been trying to evade the spotlight thrust upon him ever since a whistleblower complaint came to light in late September that suggested Trump had “sought to pressure the Ukrainian leader to take actions to help the President’s 2020 reelection bid.”

In the decade that I’ve lived in and reported from Ukraine, I’ve seen some crazy shit — a bloody revolution, the first land grab in Europe since World War II, and the shooting down of a passenger plane that killed nearly 300 people. And then, of course, we had Zelensky, the comedian who played an accidental president on TV, get elected to be the actual president. But I’ve never seen anything like the sideshow that Ukraine has become for Americans trying to understand this country’s role in one of the biggest political stories to rock DC in years.

In recent weeks, hordes of journalists from across the world — but especially from DC — have brought the swamp to the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv (and yes, it’s Kyiv, not Kiev, if you’re spelling it the Ukrainian way). They’ve filled up the pricey Hyatt, Hilton, and InterContinental hotels usually booked with businesspeople and diplomats. They’ve come in hopes of snagging that perfect quote or soundbite from Zelensky, the one that will bury Trump or save him, depending on the outlet they represent. It doesn’t seem to matter if they’re able to actually get it. As one American reporter from a major network whom I overheard talking with her camera operator recently put it, “As long as you can get Zelensky in the shot and me asking the question, we’re good.”

Besides hounding Zelensky, reporters have also bombarded those of us who’ve reported in Ukraine for years. “Hey! Love your Ukraine reporting! Wanna grab a coffee or a drink?” they’ve said — code for “Tell me all your secrets and give me your sources, and I’ll put your $1 Lvivske beer on the company card.” And when we’ve offered contacts — some whose trust we’ve spent years trying to earn — these outsiders have bombarded them with queries too, and often mischaracterized their words, actions that ultimately forced many underground.

The reporters come flying in like flaming meteorites. And they leave with the earth scorched behind them.

Do they even care? That’s not me wondering (although I do wonder); it’s the many Ukrainians whom I see every day asking me for insight into just what the fuck is going on. They’re worried about the picture that reporters and talking heads are painting of their country of 40 million people, which is struggling to root out corruption, trying to jumpstart its economy, and fighting for literal survival in a war fueled by an authoritarian ruler — Russia’s Vladimir Putin — who is hell-bent on seeing it collapse. And a scan of US media suggests their concerns are warranted.

A steady stream of outlandish headlines featuring an eclectic cast of Ukrainian prosecutors, politicians, and grifters — sometimes embodied in the same person — has been plastered all over Western front pages and scrawled across cable news screens beside the names of Trump, his enterprising attorney Rudy Giuliani, indicted business partners Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman, and the words corruption and scandal.

Ukrainians hate to hear their country spoken about that way and to see it cast as a place that is synonymous with corruption and scandal. Sure, the country might be scandal-prone and have a corruption problem, but those are their issues, dammit.

“Look, Ukraine is not about scandal. Ukraine is about opportunities right now,” Oleksiy Honcharuk, Ukraine’s 35-year-old prime minister, told me in Mariupol, a smoke-choked industrial city on the Sea of Azov, just 12 miles from the front line of the ongoing war with Russia and its separatist proxies that’s killed more than 13,000 people. Weeks before he was dragged into the Trump saga, Zelensky had announced an economic forum in Mariupol. “We have great potential for growth. We should just fix our issues with corruption, with monopolies, and so forth and so on, with vested interests,” Honcharuk continued, “We will build strong institutions and fight corruption because we have a great team here.”

But that’s not what a parade of overnight experts who’ve never or rarely been to Ukraine — yet are being marched in front of TV cameras — are saying. They’re busy mangling the pronunciation of leading Ukrainian figures’ multisyllabic Slavic surnames and wrongly referring to the independent Eastern European country as the Ukraine, as it was last known almost 30 years ago when it was still a Soviet republic. A new thing I’ve noticed that has driven me up the wall is this pronouncing Ukraine as YOO-kraine. “It’s yoo-KRAINE, for fuck’s sake!” I find myself shouting at cable news before pouring 50 grams of horilka — which, as all you Ukraine experts know, is the local vodka.

Frustrated by the ongoing war, slow pace of change, and runaway corruption that persisted under then-president Petro Poroshenko, more than 73% of voting Ukrainians chose Zelensky in April’s runoff election. Zelensky, a political novice who rose to the presidency via TV stardom — sound familiar? — ran on a platform that was basically twofold: End the war in eastern Ukraine and put an end to corruption. National polls show those issues are what Ukrainians care most about. For Ukrainians, the impeachment scandal is a distant concern.

As part of his effort to clean up politics, Zelensky promised new faces in politics. After securing another historic presidential victory, his Servant of the People party — which shares the name of the TV series that helped propel him to the presidency (check out Season 1 on Netflix!) — secured Ukraine’s first ruling majority in parliamentary elections in July. In September, when the newly elected Parliament convened, Zelensky and the party quickly went to work, passing key anti-corruption legislation, including a bill that stripped lawmakers of their immunity from prosecution and another that allows for a sitting president to be impeached for breaking the law. Imagine that.

But Zelensky has come with some baggage too. His ties to a feisty Ukrainian oligarch named Ihor Kolomoisky, who owns the domestic TV channel that aired his Servant of the People series and used to own the country’s largest bank before it was nationalized due to a $5.5 billion hole in its ledger, have prompted questions about just how clean he actually is. And his reluctance to state that he’ll try to recoup the billions of dollars stolen from the country’s banks is holding up a crucial bailout from the International Monetary Fund. Proposals from one of his party’s lawmakers and the country’s culture minister this week to prosecute journalists who “manipulate” information has also raised alarms.

But, as Kyiv has come to learn, running a country under the spotlight of impeachment is no easy task. The scandal is now threatening to slow down the momentum gained over the summer. Ukrainians see a dark irony in the fact that it was the president of the United States — a country that has arguably been Ukraine’s most ardent supporter in its fight against corruption — who has pushed Zelensky to deal in the very type of corruption he’s supposed to get rid of.

It’s no wonder why Ukrainians want simply to be left out of what is being called “Ukrainegate” and why Zelensky has gone to great lengths to avoid making any news. They see no upside to being a part of the drama. Heavily reliant on bipartisan consensus in Congress for crucial support — not least of which is military aid and upholding sanctions against Russia — they are damned if they do speak, and damned if they don’t. So, faced with an impossible choice, they’ve done their best to play it straight down the middle.

When I asked Zelensky during a marathon press conference last month what his strategy was to navigate his country through turmoil, he made clear his desire to keep himself and Ukraine as far away from what he views as a purely American political drama as possible. “I understand what you want — clearly and directly,” he said as he leaned across a long wooden table beside a stand advertising “oysters and sparkling” inside a hipster food court. “But I will not change any answers.”

As part of this effort to evade attention and not piss off either Democrats or Republicans, Zelensky has imposed what one Ukrainian administration official told me was a “no speaking, no leaking” policy when it comes to Trump-related issues. Another official who’s close to the administration confirmed the measure and described it as a “Berlin Wall of silence” put up around the presidential office. That’s quite a change from the openness Zelensky showed in June, when he invited me and other journalists to the presidential residence outside Kyiv. There we drank wine, ate shawarma (the president’s favorite food growing up), and lounged on neon-colored beanbag chairs while discussing everything from his distaste for the gaudy interior design of his presidential office to the bloody war raging 450 miles away.

Zelensky has also tried to limit his public appearances recently. But when you’re the president and you’re facing down enormous challenges in your country and constantly having to put out fires, you need to show your face. And you certainly can’t cancel prearranged events.

Zelensky hoped his Mariupol economic forum would show investors that, despite the still-simmering war, the struggling city of roughly 500,000 residents — and the rest of Ukraine — is full of potential and open for business. It was also a chance for him to show that he remained focused on his ambitious domestic agenda despite being sucked into the deepening political scandal half a world away.

I joined dozens of other journalists, on a 16-hour overnight ride on a rickety train with no open windows and a raging heater, to witness how the forum would go down — and to get a chance to confront officials who had been ignoring us for weeks.

Elated to be discussing anything but the Trump scandal with his guests — 700 of whom attended, from major companies, international financial organizations, and diplomatic missions — Zelensky practically leaped onto the event stage. Boasting of Ukraine’s capacity for transformation, he said: “We’re the Apple starting out in the garage. We’re Lance Armstrong defying the odds.” The problematic comparison to an admitted cheater seemed to be lost on him. Nevertheless, the crowd applauded, and during a coffee break, many forumgoers expressed their satisfaction with Zelensky.

But that Trump-shaped storm cloud was still there. The venue was abuzz with chatter about how Trump attempted to exploit US policy toward Ukraine for personal gain, and questions about it remained on the tips of the tongues of many foreign reporters who wrestled with the president’s beefed-up security detail.

Nevertheless, between a tasting of local dairy products and a pitch session with young IT professionals, an NBC News reporter managed to squeeze in two quick questions. She asked Zelensky: “Do you have any comment on what’s going on in Washington, DC?” and “Did you feel any pressure from President Trump?”

Zelensky’s face twisted through the usual painful motions.

“They’re a great country, great people, but I don’t know what’s going on in the USA,” Zelensky said in gruff English. “I’m so sorry. I’m the president of Ukraine, so I know what’s going on in our country.” ●