When it came to jihad, Elton Simpson talked a lot. He wasn't loud about it — he wasn’t trying to grab attention for himself. Instead he was calm, quiet, and persistent. For most of his life, his jihad was personal and internal — should he have sex outside of marriage? Drink alcohol? How could he get nonbelievers to see?

The graduate of Washington High School in Glendale, Arizona, talked so much that an FBI informant who posed as Simpson’s friend and a fellow Muslim recorded more than 1,000 hours of their conversations from 2007 to 2009. It was enough evidence to fill two bankers boxes with compact discs.

In 2010, federal prosecutors brought terrorism charges against Simpson, 25 years old at the time, arguing he lied to FBI agents about his alleged plans to travel to Somalia to join terror group al-Shabaab. It was federal public defender Kristina Sitton’s job to represent him.

Simpson and the informant “sat around and talked a lot about religion,” Sitton told BuzzFeed News. “I remember thinking, Gosh you guys have a lot of time on your hands. If you would just get a job…”

In her closing arguments that October, Sitton invoked the First Amendment. She spoke of the jihad that happens within a person as their morals are tested. She used, as an example, the fervent protesters fighting what was known as the Ground Zero mosque — a prayer center planned close to the World Trade Center that ultimately never came to fruition. Her arguments convinced the judge that Simpson wasn’t guilty of terrorism. (He was convicted of lying to the FBI and served three years of probation.)

Ironically, the face of those Ground Zero mosque protests was activist and conservative blogger Pamela Geller. Five years later, it was Geller who held a widely criticized event in Garland, Texas, asking people to draw cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, which is considered blasphemous among most Muslims.

“If you come to this country, stand for freedom. Don’t try to impose your brutal and extreme ideology on freedom loving peoples,” Geller wrote about her contest for drawings of the Prophet Muhammad. “That's why we are holding this contest.”

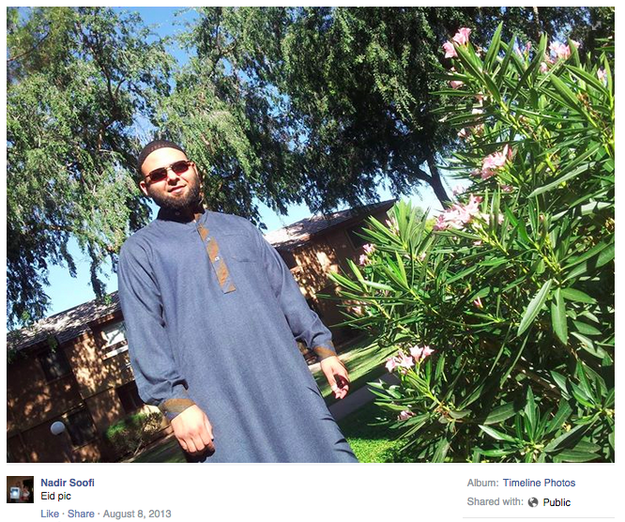

It was that event, years after his federal prosecution, where Simpson’s talk graduated into action. He and his roommate Nadir Soofi — dressed in body armor and armed with AR-15 rifles — drove up to the event in Soofi’s Chevy Cobalt and opened fire. (Geller’s group, the American Freedom Defense Initiative, paid $10,000 to hire extra security, and a police SWAT team was on standby.) An unarmed school district officer was struck in the ankle. Simpson and Soofi were fatally shot by a local traffic officer. “They were there,” Garland police spokesperson Joe Harn later said, “to shoot people.”

The forces that drive a person from rhetoric to violence are often murky and confusing. Some experts describe the personal backgrounds of radicalized Americans as otherwise “unremarkable” — this is certainly so in Simpson and Soofi’s case. The people closest to both men told BuzzFeed News and other outlets they were completely in the dark about their plans, and that even with 20/20 hindsight, the signs of impending violence were largely not apparent. Still, there are a few factors that radicals often share: a lack of economic mobility, being the target of racism, a search for identity, a sense of profound political injustice. Both men had experience with these factors — and seemingly found common ground in each other. To the outside world, everything seemed normal.

Simpson was born in the Chicago area, then moved to Phoenix by the time he was in middle school. He converted to Islam as a teen; he told others the faith helped him give up drinking and premarital sex.

He was a point guard for the Washington High School Rams and was praised in local reports as a driving force on the team. After graduating in 2002, he continued to play basketball at Yavapai College in Prescott, about two hours from Phoenix. The 5-foot-10, 180-pound freshman averaged 3.4 points in his 34 games, usually coming in late as a backup to the team’s All-American guard, the Prescott Daily-Courier reported. Simpson suffered an injury, though, and moved back to his parents’ home in the Phoenix area after his freshman year.

Over the next several years, he became a regular figure at area mosques and made friends, for the most part, with other young men who liked to talk about Islam and what was happening to Muslim people around the world.

Usama Shami, president of the Islamic Community Center of Phoenix, remembered Simpson as a normal, likable young man. Simpson had been a Muslim for years, but still had questions typical of an enthusiastic young convert. Simply put, “he wanted to know more about the faith,” Shami said.

Simpson also pitched in with volunteer projects like neighborhood cleanups and youth events. He’d play pickup games of basketball and soccer. “He was not different from any young person who was at the mosque,” Shami said.

One of his friends around that time was Hassan Abu-Jihaad, a former Navy signalman who also converted to Islam. The FBI began investigating Abu-Jihaad in 2003, after a floppy disc with classified information about the security weaknesses and movements of the USS Benson and other ships was found in the possession of a British fundraiser for al-Qaeda. Agents traced the document to Abu-Jihaad, then continued to investigate him and those around him after his honorable discharge and return to Arizona. He was arrested in 2007 and later found guilty of providing material support to terrorism and leaking national defense information.

In the fall of 2006, the FBI asked a young Sudanese man, Dabla Deng, who had come to the U.S. as a refugee to become friends with Simpson. Deng introduced himself at the Islamic Community Center, identifying himself as a recently converted Muslim — even though he’d been persecuted in Sudan for his Christian faith. Over the course of six years, the FBI would pay him $132,000 for the information he provided.

He wore a wire as he and Simpson went out for kabobs, watched videos on YouTube, and played basketball.

On March 8, 2007, FBI agents had their first face-to-face contact with Simpson. They stopped by as he and another friend were hanging out and questioned him about his relationship with Abu-Jihaad.

“Mr. Simpson said Hassan Abu-Jihaad is a good brother, and that’s all he had to say about the subject,” an FBI agent later testified. As the FBI finished questioning Simpson’s friend, he passed the time by chatting with an agent about the principles of Islam.

Deng kept wearing the wire. On July 31, 2007, the topic of fighting kaffir — nonbelievers — came up.

“The brothers in like, Palestine and stuff, they need help,” Simpson said, according to court records. He also mentioned Afghanistan and Iraq, “wherever the Muslims are at.”

“The whole thing is how you get there, though,” he continued.

In his role as a paid informant, Deng pushed him to go further: “I know we can do it, man. But you got to find the right people.”

“Gotta have connects,” Simpson agreed.

The recorded conversations, as well as surveillance by FBI agents, continued for two more years. On May 19, 2009, Osama bin Laden released a recording calling for all true Muslims to support the fight of al-Shabbab in Somalia.

Ten days later, Deng recorded another conversation with Simpson. In a snippet played at his trial, Simpson was heard singing. Prosecutors described the moment not as lighthearted, but as the conversion point, celebrating the beginning of a plan to pursue violent, international terrorism.

“It’s time to go to Somalia, brother,” Simpson said, adding they knew people there. Al-Shabaab is based in Somalia. “We gonna make it to the battlefield, akee, it’s time to roll.”

Later that year, Simpson made plans to leave the U.S. to study at a madrassa in South Africa. In one recorded conversation, he described musing with another friend about making his way to Somalia from South Africa. When he told Deng he was going to school, Deng replied, you never know who will be a fighter and who will be a scholar.

“Yeah, that’s the whole point,” Simpson said. “School is just a front. School is a front, and if I am given the opportunity to bounce…”

He was set to leave Jan. 15, 2010. On Jan. 7, 2010, agents knocked on the door of his parents' home. Simpson answered, stepped outside, closed the door, put on his shoes, and answered their questions. He said he was going to leave the following week to study in South Africa and that he was just waiting on his visa. He planned to stay for five years and wasn’t sure what he’d do after that.

They asked if he’d ever discussed going to Somalia.

Simpson said he didn’t know where they would have gotten that information.

One agent kept pushing; Simpson kept deflecting. He turned to the other agent.

“I thought we were having a friendly conversation here,” Simpson said.

The first agent continued: It’s a simple yes or no question. Had Simpson ever discussed going to Somalia?

“No,” Simpson said.

In the eyes of the FBI, that deception indicated Simpson was serious, an agent later testified.

“He had talked about obviously going to Somalia, and if given the opportunity, he would go,” Special Agent Jeffrey Hebert said. “It was our responsibility, given our investigative priorities, to try to disrupt that travel any way we could.”

The FBI scrambled to put him on a no-fly list, but they were unsuccessful.

“Nobody thought he was for real,” said Sitton, his former attorney. “Nobody did. I don’t even think [the FBI] really did.”

Simpson “wasn’t loud and in your face,” when he talked about Islam, Sitton added. “It was just kind of constant and just, ‘Come on, why don’t you believe this way. Come on, you’re a smart girl.’”

On Jan. 13, 2010, Simpson was indicted on suspicion of making a false statement in support of international terrorism. He was taken into custody and held in lieu of $100,000 bond.

With the help of friends, he made bail and was put on GPS monitoring as he awaited trial. Sitton began reviewing what she saw as “bogus charges.”

“I’ve never seen such a minor case be made so major in the federal system,” she said. “You just don’t see that.”

After years of investigation and thousands of dollars in payment to Deng, the FBI may have felt pressure to show results, she said. As the case progressed, Simpson also refused their offers of “cooperation” if he would provide information about other people, she said.

He’d already turned down an opportunity to join terrorists overseas, she argued. At one point, the FBI gave Deng $10,000 and told him to offer to pay Simpson and their other friends’ plane tickets. Deng claimed he had won the money from the lottery.

Simpson and the others debated whether the money was sinful, since it came from gambling. Simpson never took it.

The judge ultimately found Simpson guilty of making a false statement to federal agents, though there was no finding he did it to support terrorism. He was sentenced to three years probation.

“In some ways, I think [the FBI] might have struck too soon,” Sitton said. “I always thought their case was BS. They should have waited for more.”

The experience seemed to give Simpson the feeling of being an outsider, betrayed by those around him, said Deedra Abboud, a Phoenix attorney who has done advocacy work with local Muslim groups.

Simpson believed the informant was not just a friend, but a fellow Muslim. At the time, Abboud helped a few of his other friends navigate the system to get him out on bail.

When Simpson returned to daily life, though, he found that some in the Muslim community were suspicious of him — maybe he had become an informant too, they wondered.

“If he talked about anything negative, it was his frustration that the Muslims didn’t support him,” Abboud said.

Right around the time of Simpson’s arrest, in January 2010, Nadir Soofi took over the management of Cleopatra Pizza Bistro, a small halal joint in a complex near Simpson’s mosque. Soofi hired Simpson at the restaurant, and they eventually split an apartment.

Sharon Soofi said her son didn’t speak much about his new friend. She and her son would often discuss current events, religion, and what was going on in the Middle East — the family had spent about half of Nadir’s childhood living in Pakistan, years she remembers as happy ones surrounded by friends and family.

Nadir Soofi was born in Texas and raised Muslim, the religion of his father’s family. Childhood with his parents and brother meant weekends with trips to the lake or camping, hiking, and amusement parks.

“He was a normal, American kid,” his mother said.

They moved to Islamabad when he was 8 and stayed until he was 16 or 17. He and his brother attended an English-speaking school, and Nadir graduated with honors.

“I had a very good life, and so did the kids,” Sharon Soofi said.

He began classes at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City in the fall of 1998 as a pre-med student, at one point living on campus.

During his years in Utah, he racked up more than a dozen traffic tickets, many for speeding, the Salt Lake Tribune reported. In 2001, he pleaded guilty to buying alcohol as a minor. In 2002, he pleaded guilty to reckless driving, then in a separate case to driving on a suspended license, related to an alcohol offense. The following year, he was charged with distributing a controlled substance and possessing drug paraphernalia, charges which were later dropped. In July 2003, he pleaded guilty to misdemeanor assault.

He left the university in that summer without a degree. He felt like he had gotten sidetracked, his mother said, and he hoped to start over in a life guided by faith. He moved to Arizona, and over the years worked at several business ventures with his father’s help.

“He was trying to live a good, honest life — make his parents proud,” his mother said.

In 2006, Nadir Soofi became a father. He and the boy’s mother never married, but they gave their son the middle name of Azam — after Soofi’s father.

“[He was] a good son, a good father,” Sharon Soofi said.

She had moved back to the U.S., and she and Nadir’s father divorced. Her son would sometimes make the long drive from Phoenix to visit her in Texas, which he’d talk about with fellow gearheads on a Chevy Cobalt SS forum.

He became a regular poster on the forum after buying a 2008 model. He asked for advice on repairs and upgrades and also engaged in discussions on other topics.

“I freakin love this car!!!!” his first post ended.

Other posters sometimes cautioned him from jumping into big projects. One joked once that he was paranoid about cleaning deposits from the engine. Soofi responded, “Yes, I’m paranoid, neurotic, impulsive, etc… but, it is these characteristics that serve as catalyst for my yearning to know.”

Once he took over the pizza shop, he invited other SS owners to come by for a free slice on Wednesday and Saturday nights. “The pizza is no joke, many have said it’s the best pizza they’ve had!,” he wrote. “I know it sounds cliche, but I use only the best ingredients.”

The forum sometimes turned away from car chatter to politics and religion, in spite of moderators’ exhortations to keep from arguments.

Soofi joined one conversation to speak eloquently on his belief in divine creation and the words of the Qur'an.

“When came Jesus with the Gospel he was attacked by the Romans and the Rabbis, now the latest and most up-to-date form of God’s words, the Quran, is going to be attacked until the Day of Judgement,” he wrote.

His comments also often turned to conspiracy theories.

“If you drank the 9/11 koolaid an that is giving you the muslim hebe-jebies, think about this,” he said. “If the top of a building is destroyed and the bottom levels are intact, will that building collapse at freefall speed just as the towers did? Look up false flag terror attacks.”

In response to posts in the forum by U.S. soldiers stationed in the Middle East, he spoke of the influence corporations and bankers had on the "war on terror."

“Do you know Osama Bin Laden is off the FBI’s most wanted list because they can’t prove a connection,” he wrote in 2010. “All the while this country goes further into debt because of this bullshit!”

He questioned the influence of the Bilderberg Group and the Rothschilds — a Jewish family of bankers that once controlled the largest fortune in the world — on the U.S. military, and linked assassination attempts on U.S. presidents to their opposition of the federal reserve. Most of the members of the Obama cabinet had banking backgrounds, he said.

“You guys really have no clue we’re on a sinking boat!” he concluded.

Three years later, he started a thread, “Past the point of no return,” calling out the Department of Homeland Security’s stockpile of ammunition and posting an image that insinuated the department would be coming after American gun owners.

“The inevitable result of imperialistic megalomaniac bankers taking over the country a la Federal Reserve Bank and the Banking Cartels!” Soofi wrote. “The founding fathers warned about today’s reality.”

In Soofi’s several hundred posts, he was almost always friendly and thankful for the mechanical expertise of the community. The complimentary, brotherly tone vanished at any insult to Islam or flippant invocation of terrorism.

After one post about a successful car trade contained the word “congratulations” in Arabic, one commenter replied “Oh noes! A terrorist!”

Soofi responded quickly.

“You ignorant bigot, anyone who knows Arabic is a terrorist now? Pull your head out son.”

The two traded insults, even as the original poster said he recognized the joke.

“Please soofi, calm down, we don’t need to start fights over stupid things, honestly what he said is something I would have said, and I’m Arab.”

By 2013, the pizza business had changed ownership. Soofi began driving a cab, earning about $2,500 a month with a couple hundred dollars in savings. That year, he also sought a formal custody arrangement with the mother of their 7-year-old son. The child could remain primarily with his mother, who had married, Soofi indicated in court documents. But he sought joint legal decision-making, a month of continuous custody over summer break, and an appropriate holiday schedule according to his religious beliefs.

“I request that [our son] only celebrate my religious holidays,” responded the child’s mother.

After mediation, the court granted Soofi the right to have his son Sunday–Tuesday each week as well as the two Eid holidays, while the boy would remain with his mother for Christmas and Easter. Both parents were allowed to take the boy to their own places of worship while he was with them, and the judge ordered them to make major medical, educational, and religious decisions together.

“Both parents are fit and proper parents and are able to work together to provide and care for the minor child,” the court ruled.

Soofi was also ordered to pay $389 in child support a month, as well as chip away at a lump sum of $4,800 in past support in $100 per month installments.

He turned his talents to carpet cleaning, another venture started with his father. He ran Effinity Solutions out of the apartment he shared with Simpson, spending more time driving his work van than his beloved Chevy.

“As far as I knew, he was working hard to build the carpet cleaning business,” his mother said.

But earlier this year, something did catch her by surprise. Nadir told her he had bought an assault rifle. (It’s unclear if it’s the same one used in the attack.) He’d never had an interest in guns before, she said.

“I came down on him pretty hard about it,” Sharon Soofi said. “I didn’t want my grandson exposed to weapons like that.”

He later told her he’d gotten rid of it and apologized for worrying her. She believed him.

“I thought I had gotten through to him when I spoke to him about owning the weapon,” his mother said. “I don’t know that he was upfront with me about what was going on.”

What isn’t clear is how Simpson and Nadir Soofi went from being friends who talked Middle East politics to would-be partners in domestic terror.

Soofi’s family seems to believe that Simpson became a dominant force in Soofi's life, pushing more radical ideas on him. Soofi’s brother, following a divorce, stayed at the Phoenix apartment they shared. Sharon Soofi said Nadir Soofi was trying to help his brother, but Simpson drove a wedge between them.

Simpson “had a very strong influence on” her son, she said. Otherwise, she said, “I don’t know what to think.”

Both men seemed to drop off the FBI and Muslim’s community’s radar.

After almost a decade, FBI agents in 2014 had closed their investigation of Simpson as he completed probation. “The Phoenix field office saw no further indication of threat connected to him,” FBI Director James Comey said.

And Shami, the president of the Phoenix Islamic center, said he had last seen Simpson after a Friday prayer in early 2015. “I shook his hand after that and asked him if things were OK. And he said yes,” Shami said.

Simpson’s family released a statement that they had no idea of their son’s mindset. “Just like everyone in our beautiful country, we are struggling to understand how this could happen,” the statement said.

Simpson’s friends also didn’t see anything coming, said Abboud, who had helped them in 2010. They showed her recent text messages from Simpson; all seemed normal.

“It was so tame,” she said. “There wasn’t even a lot of conversation.”

But Simpson knew he had been under watch by the FBI, she added, so his concealment of criminal intentions made some sense. When his grandmothers died out of state, years before, he found out he had finally been put on the no-fly list. He also felt the larger Muslim community treated him unfairly after his arrest, she said.

These are the kind of emotions extremists such as ISIS prey on in their messages to potential followers, Abboud added. The religion itself isn’t really the attraction.

“It’s talking about injustice,” she said. “People who feel they’ve had an injustice or there’s social injustice are more susceptible.”

Simpson’s former attorney said Simpson didn’t seem particularly upset after the 2011 conviction.

“If anything, the investigation made him a better terrorist,” Sitton hypothesized. “They prosecuted him. They showed him they had the capability, the time, the energy, the desire to follow him around 24/7. He learned to keep it quiet, to not trust anybody.”

In April, Simpson’s pro-ISIS Twitter account @atawaakul cautioned his followers from being open with their loved ones.

“Always remember, your parents, friends and neighbors can quickly turn into agents out of their ‘love’ for you. Some do not understand this.”

His activity on social media drew renewed interest from the FBI, and agents reopened their investigation in March. By then, Simpson claimed he had already been suspended by Twitter several times, a frequent occurrence for those voicing support for ISIS.

“That investigation, as all of ours do, involved a variety of techniques to try to understand what he was up to and to get a better sense of him,” FBI Director Comey said.

Simpson tweeted with other ISIS supporters, and the group later claimed responsibility for the attack — no evidence has shown they formally ordered Simpson and Soofi’s actions or provided support.

Around the time Simpson was attracting federal attention, Soofi was trying to sell his car online. He listed it at $8,950, a price some forum members found too high. Back in 2009, Simpson had told his friend, the FBI informant, that selling his car could get him the money for a plane ticket to Somalia.

Soofi dropped the price to $7,500, but it still didn’t sell. Three weeks later, both he and Simpson got into the Cobalt SS and began the 1,101-mile drive to Garland, Texas.