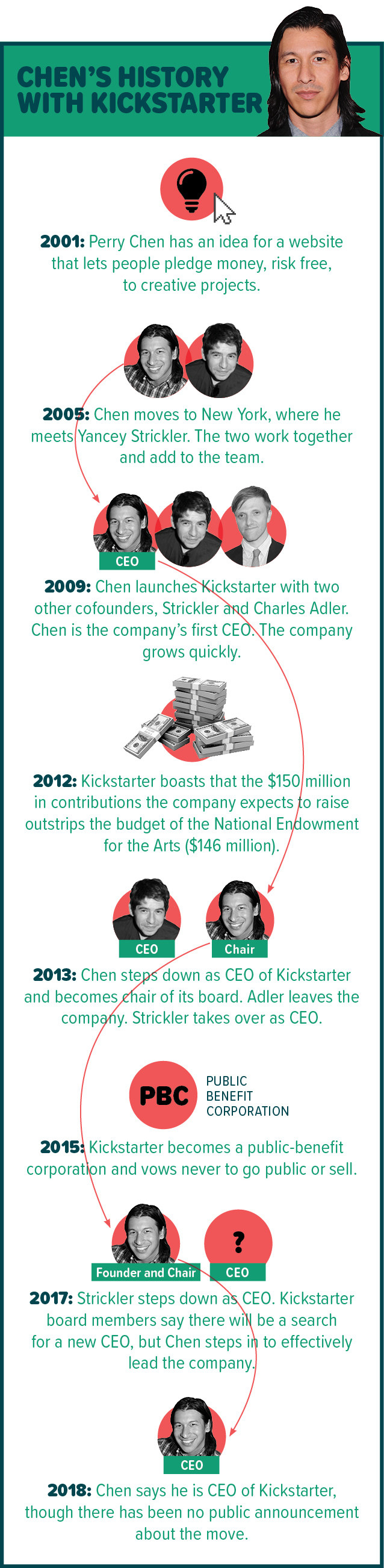

Founders of successful startups hold mythical status in the tech industry. But while myths are often inspirational, they are also frequently meant to serve as cautionary tales. Case in point: Kickstarter principal founder Perry Chen — who took over the company from cofounder Yancey Strickler in July of last year, then said in March that he had quietly become permanent CEO — is alienating staff and sowing chaos at the popular crowdfunding platform, BuzzFeed News has learned.

Since Chen took over, about 50 out of 120 Kickstarter employees have left. Among the departed: seven of the eight members of Strickler’s executive team. In interviews with BuzzFeed News, 24 sources close to Kickstarter painted a picture of a company stumbling under the guidance of a returning founder who insists he alone is the person to steer it in a definitive new direction.

Fifteen current and former employees described Chen’s attitude since coming back as following the so-called visionary founder myth — the belief by some founders that they are uniquely imbued with the ability to envision their company’s future clearly and overcome its worst crises. It’s an arc that the tech industry has largely embraced, from Steve Jobs’ legendary comeback to Apple in the late ’90s to today’s embattled Twitter searching for redemption under the guidance of founder Jack Dorsey.

“I always, in a way, wondered — would I ever come back?” Chen told BuzzFeed News in an interview, during which he also confirmed for the first time publicly that his once-interim role leading the company had been made permanent. “In truth, I think my hope was that I wouldn’t. But I came back because I think the company needed it.”

“You can’t alienate the workforce on the assumption that you’ll be able to replace them, or that it won’t cause fractures in the company.”

In interviews, employees said Chen strongly exerted his will on the company — making sudden changes to planned-out Kickstarter features, scrapping project timelines at the last minute, forcing out highly respected employees, and trying to shake up office culture in ways that struck the rank and file as simply bizarre. (In the fall, he brought in people dressed up as dinosaurs to wander the office for a week as performance art.) They said his top-down approach to leadership bred discontent — that, in the words of one, Chen “pretty clearly thinks the company is his” and not employees’, and he always seemed “surprised” and “defensive” when he got pushback. And they asserted that after close to a decade spent growing up and settling into a more mature corporate culture, Chen has thrown the organization into chaos in a rush to bring it back to startup-esque idealism.

“You could argue that his position is ‘I’m going to make these changes, and people can come along. Or if they won’t, they can work somewhere else,’” said one former employee.

“But,” the ex-employee continued, “you can’t alienate a significant portion of the workforce on the assumption that you’ll be able to replace them, or that it won’t cause serious fractures in the sociodynamics of the company.”

A Kickstarter spokesperson disputed the characterization that Chen’s management style was overly autocratic, as did the CEO himself. “I care about making the best decisions possible, and I seek input and collaboration,” he told BuzzFeed News. “That said, it is important for a leader to make challenging decisions even without full buy-in or consensus.”

In 2001, Chen had the idea for an online platform through which crowds could pledge money for a project, risk free. Kickstarter launched in 2009 and almost instantly saw meteoric growth. Within a year, Time magazine named Kickstarter one of the “Best Inventions of 2010.” Within two, the company was boasting that its $150 million in contributions outpaced the National Endowment for the Arts. In 2014, Chen stepped aside as CEO to become the company’s chair and Strickler, another cofounder, took over. The next year, Kickstarter users pledged more than $600 million for nearly 80,000 projects, according to research firm ICO Partners. It was a rocket.

What’s more, Kickstarter positioned itself as a new kind of company, with a “creator-centric mission” that balanced profit with arts patronage and attracted many of its early staff. After Strickler took over, employees said, he hired deliberately, and personally pushed to make diversity a priority: Of the eight members of Kickstarter’s executive team under Strickler, only two were men. A former employee called the company’s culture at the time “mission-centric,” but with “an injection of practicality.”

In 2015, Kickstarter formalized this commitment to community, restructuring its business model to become a public benefit corporation (PBC) and vowing to never go public or sell. Even as growth slowed, the company promoted itself as a cultural standard-bearer, a new and admirable kind of startup. According to its first public benefit statement, released in March 2017, the company has engaged in various public policy issues. It also boasted that a majority of its staff were women and that it paid its CEO far less than other companies relative to what an average employee earns.

Chen takes credit for restructuring Kickstarter into a PBC — an idea he dreamed up while on vacation, according to a recent Fast Company profile. He was in Florence when he spontaneously flipped open his laptop and “began to type some of the thoughts swirling in his head.” The result was a 1,000-word email that Chen sent a month later to Strickler, then the company’s CEO, with the email subject line: “existential kickstarter.”

Restructuring into a PBC was “strongly supported internally,” according to one ex-employee. “It sounded like a collaborative thing and everyone was on board.”

“Those,” the employee added, “were the good days.”

In retrospect, sources said, the move to PBC was a sign of how much Chen exerted his preferences on the company he founded, whether or not he was in charge of its day-to-day operations.

According to ex-employees, in the three years he ran the company, Strickler worked hard to mature it thoughtfully and sustainably. Sources describe him as a great storyteller and Kickstarter evangelist; one noted that he was “really well-loved.” Under his leadership, employees said, they took their jobs very seriously and enjoyed their work. Kickstarter was stable, if not growing at the rate it had in its infancy.

“It wasn’t like the company was going to close down or anything — we were still going to be profitable last year,” a former employee said of Strickler’s tenure. “But we weren’t necessarily seeing the blockbuster growth that we had always seen.” Meanwhile, the employee said, a company like Patreon — a newer subscriber-based funding platform that has racked up more headlines, and more venture capital compared with Kickstarter in the past few months — was “seeing that blockbuster growth.”

And at the same time, the company had started to wrestle with the fact that the creative projects it felt were core to its mission were not, ultimately, what brought people to Kickstarter. Games, design, and technology projects have added up to more than three-fifths of the total dollars pledged to the platform since its inception, and some employees worried that Kickstarter was becoming a catalog for gadgets like the Coolest Cooler and the Pebble smartwatch — “a cooler version of SkyMall,” as one put it.

So Strickler brought on accomplished executives hired for their expertise to help move the company forward. Former employees described how for the first time, it felt like there was an “adult” executive team in place — people who had years of experience at places like Etsy, Artsy, Adobe, Ideo, Google, and Venmo; who understood how to lead teams; and who created a roadmap and a new strategy for the company. Together with Strickler, they came up with a new digital strategy, hired a brand agency, and devised a new product roadmap for Kickstarter, including the initiative that would become Drip, designed as the company’s answer to Patreon.

Strickler was out before Drip launched. He announced his resignation at a company all-hands in July 2017; afterward, Chen took the stage and promised to help the board search for a new CEO, while continuing to support the executives Strickler had hired. But in March, Chen confirmed to BuzzFeed News that he had taken over as CEO of the company, though there has been no public announcement or written communication about the move. An early list of potential CEOs was put aside and candidates were never interviewed, Chen told BuzzFeed News.

Several sources close to Strickler’s resignation said he did not want to step down as CEO, but was asked to leave by Chen and the board, and ultimately respected their decision. Since stepping down, Strickler has not held a strategic or advisory role at Kickstarter, though as a cofounder he is still one of the largest shareholders of the company.

Central to Chen’s self-perception, employees said, is the notion that he and he alone can protect the company’s ideals.

“What I think was most disappointing,” a former employee said, “was that Chen failed to believe that we cared about Kickstarter’s mission as much as he did.”

“What I think was most disappointing was that Chen failed to believe that we cared about Kickstarter’s mission as much as he did.”

Sources said Chen was critical of the direction the company had gone in under Strickler. He wanted to make Kickstarter less corporate and more freewheeling — much to the frustration of the employees who’d spent years in the trenches doing just the opposite, growing it from a scrappy startup to a mature company. “It’s structurally damaging the business model in the interest of returning to a different era,” said one former employee, “when the world has already moved on.”

“Maybe when [Chen] had left, Kickstarter was less of a real professional tech company,” a different ex-employee said. “But it didn’t feel like he cared that there were over 100 people there working on their careers. It meant something to us. It wasn’t just a fun art project. It was like, ‘No, this is paying my bills.’”

In his first few weeks at the helm, Chen scrapped the roadmaps that had been developed at Kickstarter and by the agency it hired, and insisted on small things like the name of Drip, even when employees pushed back on how it sounded. One source said Chen seemed to think his and only his ideas were good — “not that an executive team is a broad group of people to consult for their understanding in their domain.”

In an interview Chen argued that under Strickler, Kickstarter had become too bureaucratic. “Adding support and systems for employees is good and necessary as a team grows,” he said. “But over the previous few years Kickstarter had started to adopt an approach that better fit 500-plus-person companies.”

He drew a comparison between Kickstarter and some of its siblings in the New York startup scene, many of which have stumbled as they’ve aged. “We’ve always been here in New York, where there’s a cohort of startups — Etsy, Meetup, Foursquare, Tumblr,” he said. “I think those companies diverged from where they wanted to go.”

After Etsy went public, it faced intense pressure to start acting like a shareholder-focused company — then it abruptly fired its longtime CEO. Meetup has been acquired by the coworking startup WeWork. And Foursquare and Tumblr have floundered in their own ways.

“For us,” Chen continued, “if we had a period of time where we weren’t living up to our expectations and our challenges, but now we can correct for that, I think I would take that, versus maybe where the other companies went.”

But his attempts at correction didn’t always land. There was the time that he and his assistant took over the library — a quiet zone — and played music. And then there were the people dressed up as dinosaurs.

At first, employees thought it was good, dumb fun — but later in the week, sources said, the dinosaurs wandering around all day started to interfere with work. Finally, one afternoon, the dinosaurs came in with a troupe of performers dressed in army garb playing saxophones and stomping around. (A video of the mayhem was seen by BuzzFeed News.) A handful of employees walked out.

Many employees felt the incident epitomized Chen’s disconnect in wanting to “shake up” Kickstarter’s corporate culture but not knowing how. Soon afterward, Chen sent an apology email, explaining that he thought having performance art in the office would be fun.

But nothing has roiled Kickstarter more thoroughly in the last several months than the constant turnover for which employees blame Chen.

Sources said that soon after he took over the company, Chen and some members of the executive team realized they did not work well together. The executives were frustrated, two sources said, with what they saw as Chen making unilateral company decisions on projects they had largely overseen.

Chen then started holding one-on-one or small-group meetings, sometimes on weekends, at the office and his artist’s studio around the block from the Kickstarter office, two sources said, and consulted a new circle of people, outside of the executive team, for strategic decisions on Kickstarter. This made some executives feel undermined, the sources said, and compelled them to quit.

“When I arrived mid-year there were few open decisions to make, though I did make some material changes to two of the larger projects underway,” Chen told BuzzFeed News. He denied meeting with a “group of people outside of the company,” though he did not directly deny that he had started to consult a new circle of people more than Kickstarter’s own executive team.

Since Chen took over, seven executives have left Kickstarter: the head of HR; vice presidents of engineering and product; senior vice president of operations; chief financial officer; general counsel; and general manager.

These were, said one ex-employee, “super competent, professional people that are well-respected above and below them, and in the industry, and [Chen] just didn’t give a shit.”

“Kickstarter had hired kickass women that the industry loved. He burned those bridges — not just for Kickstarter but for all of us.”

“When I came in I worked in good faith with the existing executive team to put us on a better path,” Chen said in response to questions from BuzzFeed News. “There were some cases where I didn’t find the same willingness to work together, and some cases where I, unfortunately, realized we’d be better served with new leadership. In both types of cases, there was a lot of care behind the scenes into those transitions.”

Meanwhile, Chen has surrounded himself with figures from Kickstarter’s early days, including Cassie Marketos, its first employee, as VP of community strategy, and Andy Baio and Fred Benenson as Kickstarter fellows. To fill the holes left by executive departures, Chen hired Sarah Hromack to be Kickstarter’s first “chief culture officer” and Jamie Wilkinson as its chief product officer. (Five months after she started, three sources confirmed, Hromack ended her tenure at Kickstarter. She did not comment for this story.)

A BuzzFeed News analysis of changes to Kickstarter’s staff page between July 8, 2017, and April 3, 2018, showed that 47 of about 120 employees had left; a former employee said it is “fair” to say “about 50” people have departed from Kickstarter in the last year or so. The former employee also told BuzzFeed News that people had been leaving before Chen returned, but the rate of people leaving had increased after he took back the reins. (Kickstarter, however, noted it was not downsizing; a spokesperson said the company has hired 36 people since September.)

Robert Siegel, a lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Business who studies strategy and innovation, told BuzzFeed News he didn’t think the rate and volume of employees leaving Kickstarter over the past few months was “normal.” “This could be a situation where a strong personality is accelerating the decline, or it’s possible that this is a company fixing itself. But it’s certainly not normal.”

Multiple former Kickstarter employees cited one incident in particular as their reason for quitting. Late in 2017, two women executives announced they were leaving the company at the same time. Chen called a company all-hands so that employees could ask questions, and one woman asked Chen whether Kickstarter was still committed to women in leadership given that two leaders were exiting the company.

As five sources recalled, Chen responded by saying that in case the staff hadn’t noticed, he himself was a person of color — but did not address how to support women in leadership. He gave a “wild” and “rambling” answer that included how he was raised in New York City in government housing and, the sources said, brought up his disadvantages and lack of privilege in a way that struck them as self-centered and defensive.

Kickstarter disputed the characterization of this response, saying that Chen meant to convey that Kickstarter's commitments to fighting inequality in its PBC charter were initiated by him and informed by his experiences.

“Issues of systemic inequality are issues that I care about deeply,” Chen said in response to questions about the meeting from BuzzFeed News. “But I do not, and would never, equate or conflate individuals’ experiences of race and gender — reductive analogies are inherently divisive and unhelpful. In the context of that conversation I understand how it came off, and I own it.”

But still, one ex-employee said, the incident soured her on Chen — and Kickstarter. “I thought to myself, What future do I have as a young woman at a company like that?” she said. “Kickstarter had hired kickass women, people I was excited to learn from and that the industry loved. He burned those bridges — not just for Kickstarter but for all of us.”

Diversity statistics shared with BuzzFeed News show that Kickstarter’s male-female representation has been at near-parity in the past two years, but the proportion of female employees trended slightly downward from December 2016 to December 2017, while racial diversity remained more or less the same. Executive team composition went from six women and two men, three of whom were people of color, under Strickler to three men and two women — only one a person of color — under Chen.

“If the CEO leaves the company, you’re going to get a different CEO who will probably have different values and a different mission.”

Shortly before Strickler left, he offered a job to Erica Baker, an engineer and a visible advocate for diversity in tech, as the company’s first director of engineering. “To get to work with a whole group of badass women, women at the top of the company running the organization? That was a big deal. I was so excited about it,” Baker told BuzzFeed News.

After Strickler stepped down, Baker changed her mind. “That’s the way it goes: If the CEO leaves the company, you’re going to get a different CEO who will probably have different values and a different mission,” Baker said. “That shuffle reverberates throughout the whole organization.” She ended up taking a job at Patreon.

When asked about the challenges during the company transition, Chen told BuzzFeed News, “I think it was stressful for everybody.” Among Kickstarter’s staff of approximately 120 people, only 20 had been at Kickstarter when Chen left in 2013, he said, and he was acclimating. “To me, there were a hundred-something new people all at once. They also didn’t know me,” Chen said.

“When I came in, my hope was not to make any major changes,” he said. “And in truth, I think I found that more change was needed than, I think, any of us thought.” Chen added that the changes the company went through in the fall “weren’t personal” and that Kickstarter would “always be a place where great women can contribute, grow, and thrive.”

Toward the end of 2017, some Kickstarter employees threw a party for all the employees who had recently left the company — a gathering to honor “old Kickstarter.” People got plastic trophies as a prize for weathering the past few months. A handful of former company executives showed up at the party, including Yancey Strickler. When attendees saw him, they all clapped.

As negative as the departing employees felt in their last few days, many said they still believe in Kickstarter and its original mission: to help bring creative projects to life. Even though it didn’t work out for them, employees said, they’re still rooting for the company — and what it stands for.

“I believe the company is an important force in the world now,” said a current employee. “And I still believe in the opportunity it has to be an even greater force for good.”

In an interview, VP of community strategy Marketos told BuzzFeed News that she “could tell people were having a rough time” during the transition, but emphasized that now “it feels like things are falling into a really good place.”

“Maybe you start to get a reputation in the industry as not the most stable place to work.”

Kickstarter investor and board member Fred Wilson rejected the notion that the company chaos was anything but growing pains, which have been resolved. “Turnover is pretty common when there is a leadership change,” he wrote in an email to BuzzFeed News. “I am very supportive of the way Kickstarter chooses to manage its business and make decisions and I have great confidence in Perry's ability to lead it down this path. Kickstarter is an unusual company, that charts a different path, and my role as an investor and Board member is quite different as a result.”

He’s right. Since it is a PBC, Kickstarter doesn’t have investor, shareholder, or founder pressure to go public.

“For most companies, money is a really easy thing to orient toward,” a current employee told BuzzFeed News. “In the absence of that, how should a for-profit company that’s trying to be sustainable and increase its impact move forward?”

But while it wrestles with the existential questions, Kickstarter still has to figure out how to mitigate for lost staff, and rebuild what’s been broken.

There’s “a huge amount of institutional knowledge lost” in terms of what Kickstarter has tried and what has not worked, a former employee told BuzzFeed News.

“On the whole, is it better than it was in the fall?” another former employee asked. “I don’t know how it could have gotten worse. … But there are still some people at the company who say, ‘This isn’t what I signed up for.’” Three former employees brought up the idea that the turmoil the company has faced in the past few months was antithetical, even “hypocritical,” to Kickstarter’s mission.

And then, as a former employee said, “maybe you start to get a reputation in the industry as not the most stable place to work.” ●

CORRECTION

There were eight people on Kickstarter's executive team under former CEO Yancey Strickler, not including Strickler. An earlier version of this story misstated the number.