OKATIE, South Carolina — Wherever Valerie Biden Owens goes, as she tries one last time to make Joe Biden president, a local Democrat reads dutifully from her bio.

So impressed was Biden Owens’ host at an event last month in Allendale, South Carolina, she read word for word it as it appears online — taking nearly five minutes and sparing no detail. (“Valerie’s weekly seminar, ‘Politics, Up Close and Personal,’ was the most highly attended seminar for the Fall 2014 semester.”)

“Ladies and gentlemen,” she finally concluded, “this is a very accomplished lady who is here today. She could be running for president herself with all of that.”

In these moments Biden Owens, 74, alternates between masking her delight and playing along. “Are you still awake?” she humblebragged in Allendale, one of several places she visited on her brother’s behalf in the important early primary state. “One helluva woman!” she agreed the next morning in Beaufort, slapping her knee for effect.

The first two times Joe Biden ran for president, his younger sister served as “campaign chair,” with an in-name-only campaign manager working under her. In 1987, when one adviser came in to run everyday operations, Biden Owens “was still numero uno,” longtime Biden aide Ted Kaufman recalled years later. When another guy took the job in 2007, one newspaper reported, “the senator told him that his sister's judgment, if it were to come into conflict, ‘would matter more.’”

The family — the Bidens — always ran Joe’s campaigns, from the fundraising to the organizing. If you listen to the candidate or talk to the people around the family or read the stories about them over his many decades in politics, you’ll learn about pivotal meetings at the Biden family home, and the decisions his brothers, his sons, and his sister helped him make.

But there’s been no one more essential to Joe’s career than Val. Friends talk about how they complete each other’s sentences, how she helps find his voice. His tragedies — the car crash that killed his first wife, Neilia, and their daughter weeks after Val steered him to a surprise Senate victory in 1972, the loss of his eldest son, Beau, to brain cancer in 2015 — are her tragedies. Many of his political successes — from that first Senate race to the meeting with top Obama advisers at her home that helped him land the vice presidential nomination — are her successes.

She is, in the words of deputy campaign manager Kate Bedingfield, the “emotional guardrails” for her brother. “Val,” Bedingfield told BuzzFeed News, “is kind of the connective tissue throughout the course of the campaigns from '72 to today." Last spring in Philadelphia, when he spoke at the first major rally of his 2020 campaign, she mouthed along from the second row, nodding emphatically on key beats.

This campaign is different, though. Biden Owens remains close by — as her recent surrogate work suggests — and in touch with her brother’s top aides. But for the first time, she has no role or title or official decision-making authority.

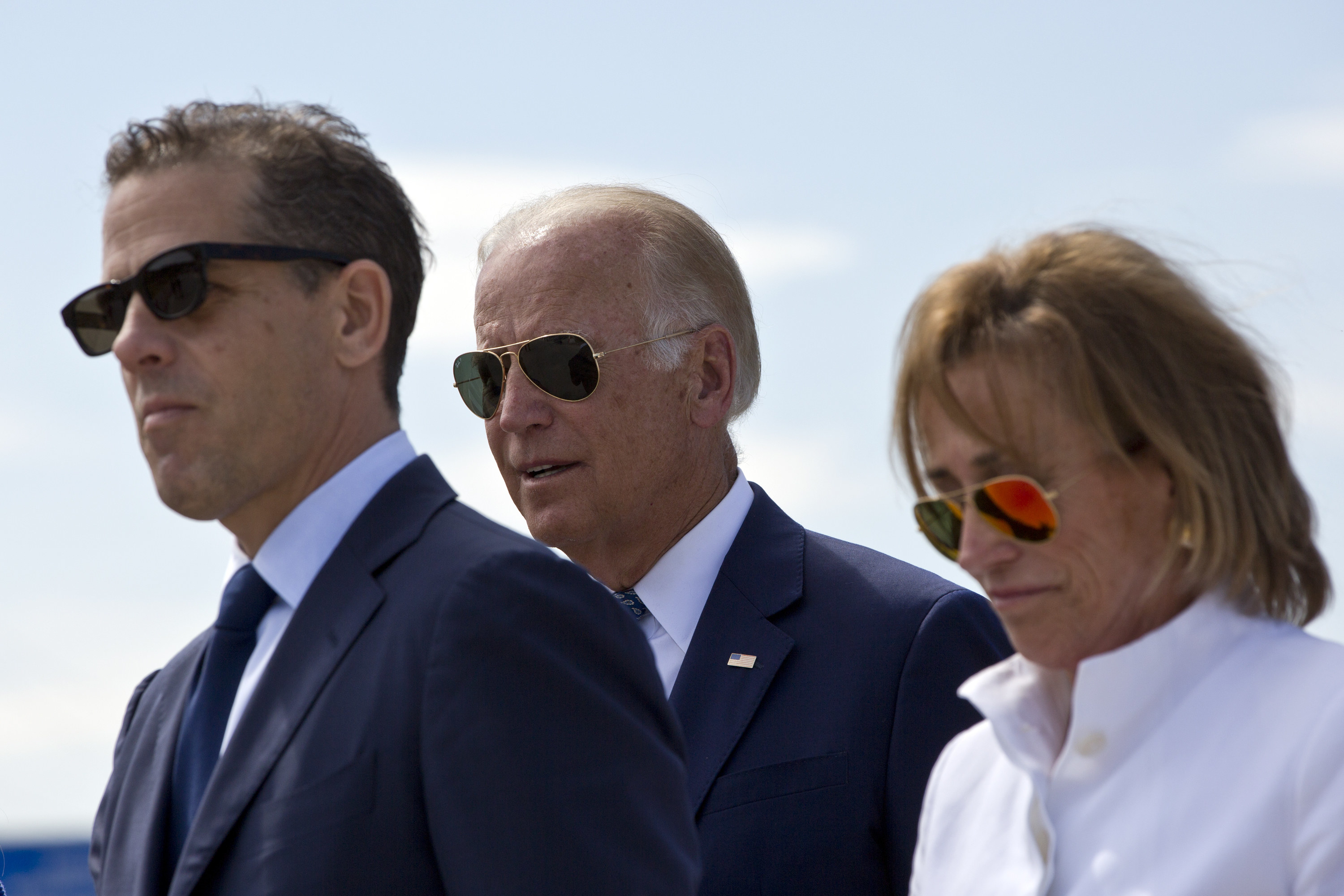

Recent polls show Biden’s early frontrunner leads narrowing, in several cases disappearing. He is struggling to raise money. There are concerns about his age and his compatibility with the new progressive left. And President Donald Trump is spouting unfounded accusations and demanding that foreign governments investigate Biden and the overseas business dealings of his youngest son, Hunter.

“I have been his campaign manager since high school — class president,” Biden Owens told the small group that gathered to hear her in Beaufort. “This is the first time I haven’t managed the campaign, and I want to tell you, it’s damn frustrating!”

The Biden family is steeped in self-reverence. “Your word as a Biden” — a favorite family phrase — can scan as a shibboleth meant to project infallible integrity.

In his 2007 book Promises to Keep, Biden wrote about an early lesson in loyalty involving his sister. The nuns at their Catholic grade school had deputized him as a safety patrol lieutenant on the bus, a post that came with a badge and an obligation to report bad behavior. “She’s your sister, Joey,” his father told him when he sought advice after witnessing Val cause trouble.

“I knew what I had to do,” Biden recalled. “The next day I turned in my badge.”

It wasn’t a huge deal when Joe asked Val to manage his first campaign: a 1970 run for a seat on the New Castle County Council. It was a Republican district, and Biden, then 27, didn’t expect to win. But “Valerie Biden did not go into any race to lose, Republican district or no,” he wrote in 2007. “She was a methodical organizer. She got voter records going back several elections, had an index card for every block in every neighborhood, and started recruiting block captains.”

Biden won by about 2,000 votes. His next move was bolder: a US Senate bid at age 29. Election Day was weeks before he’d be constitutionally old enough to serve. And he was taking on J. Caleb Boggs, a Republican fixture in Delaware. He turned to Val again.

“Now that didn’t make sense to a lot of people, because all the pundits were men — and I’m not bashing men, I love men,” Biden Owens said during her recent South Carolina travels. “But they did believe at the time, in ‘72, that a woman’s role in a campaign was to open and close the headquarters and to get coffee.”

Ted Kaufman, recruited by Val that year as a volunteer to coordinate get-out-the-vote efforts, and later one of Joe’s most trusted advisers outside the family, recalled Biden being thought of early on as the party’s “sacrificial lamb” against Boggs. “Someone said they thought it would be Joe Biden,” Kaufman, who decades later succeeded Biden in the Senate, said in oral histories he gifted to the Senate Historical Office in 2013. “Then someone said, ‘Well, who’s going to be his campaign manager?’ They said, ‘His sister, Valerie.’ Another guy said, ‘Great ticket. They ought to reverse it!’ Valerie had been a top student at the University of Delaware. She’d been homecoming queen. She was an absolutely incredible person.”

The 1972 campaign was a family-led operation from go. Neilia represented her husband at coffee meetings. Brother Jimmy handled fundraising. Brother Frankie, still in high school, helped find young volunteers. Val, a high school teacher at the time, pushed her students to help. And, in a trolling move, she booked the biggest, nicest venue in Wilmington for the victory party months before the election.

Joe considered not taking the Senate seat after the accident that killed Neilia and their daughter, Naomi, who had just turned 1 — and that Beau and Hunter survived with serious injuries. He was able to make it work, thanks in no small part to Val giving up her teaching job and moving in to care for the boys. “She did the cooking, the shopping, the laundry, and the driving. And while I was in Washington or on the road, Val was there every day,” Biden wrote in 2007.

But she never let on that her marriage was failing. “I knew my life according to Valerie Biden [was] over,” Biden remembered her telling him later. “I had really blown it. I was going to disgrace myself, the family, the Church, all my dreams. I made a big mistake. But your life was shattered. You were bleeding from every pore, and I was trying to shore you up, to be a happy face for you and the boys.” Eventually, Joe reintroduced her to his law school friend Jack Owens, years after his initial attempts to fix them up failed. (They married in 1975 and have three adult children.)

By the time Joe ran for reelection in 1978, he was remarried, to the former Jill Jacobs. Val managed that campaign, too. An item the following year in the Wilmington News Journal labeled brother and sister an Alphonse and Gaston act after a mutually admiring turn — “I am very easily manipulated by Valerie.” … “Joe is a great man.” — on a local TV show.

“Thank God the election is six years away,” Joe told the audience, “because people probably think we’re both nuts.”

When he finally ran for president, for the Democratic nomination in 1988, the campaign didn’t make it past 1987. But it started with so much promise, on a June day at the train station in Wilmington. Val, of course, was master of ceremonies, and it took her nearly three minutes to introduce all of the Biden family and extended family on the makeshift stage with her.

“This is the family that stands behind Biden,” she said as she squinted out into the crowd, “and this is the family that’s out front for him.”

Thirty-some years later, Biden Owens clocked two long October days across South Carolina’s Lowcountry, hitting smaller cities and retiree resort towns.

She had handshakes and half-hugs. She had her speech, which emphasizes how her brother overcame the bullies who taunted him over his stutter — here she draws a direct line between the bullies and Trump — and how he drove her to succeed as a woman in politics. She had jokes. “This is not vodka in here!” she said playfully as she sipped from a water bottle just after 9 a.m. in Beaufort.

Later, at a Hilton Head luncheon, Biden Owens took a moment to embarrass Maureen, her “longest and dearest friend” from Delaware who now lived on the island and had come to hear her speak. “She dated Joe all through high school and college and then dumped him,” she said ruefully. Suddenly her microphone cut out.

“Did you do that?” she asked Maureen.

The final stop on Biden Owens’ two-day, five-city swing through South Carolina was a half-empty Mexican restaurant in Okatie. About a dozen people were waiting, some enjoying a mid-afternoon Corona, most unaware the woman about to speak was, more than the former vice president’s kid sister, the chief architect of his political career. Twenty-three minutes later she was all done and ready to take a few selfies, leave behind the smell of scorched tortilla chips, and catch her flight home. And that’s when the impromptu Q&A session broke out.

An admirer in the audience wondered how her moderate brother could win over left-wing voters. She started her answer by channeling Biden’s sometimes stubborn resistance to the complaint that he’s not liberal enough, arguing that his policy proposals are misunderstood — “For example, climate change, I mean, who’s going to read it?” — and as progressive as anyone else’s. She predicted Elizabeth Warren eventually would back away from her support for Medicare for All, or at least from her insistence the program wouldn’t raise taxes on the middle class.

Eventually, she got to the point.

“Sometimes people don’t want to listen,” she said. “And I think in truth there are groups in our party who simply don’t want Joe to be president. Now, they don’t think he’s an Evel Knievel. They just think he’s past his time. Or he’s too old.”

Biden Owens stressed, in a brief exchange with BuzzFeed News after her Beaufort visit, that her frustration over not being in charge of the 2020 campaign does not reflect any resentment or disagreement over how it’s running without her.

She knows it’s time for a new generation to take over, and she tells her audiences that her job as vice chair of the Biden Institute, her brother’s public policy think tank at the University of Delaware, does not allow her to engage in politics full time. (She declined, through the campaign, a request for an interview.)

“You could always get another campaign manager, which we have done, a very good one,” she told the Hilton Head luncheon crowd, offering a vote of confidence in Greg Schultz, a tech- and data-savvy adviser who had no strong ties to the family before going to work for Biden in 2013. “But you can’t get another sister.”

Schultz joined the Biden team after coming up in Democratic politics in his native Ohio, where he had high-level roles in both Obama–Biden campaigns and ran the local party in Columbus. Biden Owens may not loom over him as an all-powerful campaign chair, but Schultz knows her opinion matters. He talks to her several times a week — “I actually, for years and years, called her Aunt Val,” he told BuzzFeed News in an interview — and values her advice. She has embraced the new technology that didn’t exist the last time she ran a campaign. She also can help cut through her brother’s stubbornness and longing for the good old days of Joe and Val.

“One of the things she’s been helpful on is, if I or some other folks on the campaign team have some ideas that we think might be a good idea for the VP to do, she’s really good at, like, ‘Oh, you should mention to him that we did something very similar in 1986 or 1992,’ or whenever,” Schultz said. “It always helps, because it allows us to show up to the VP with an idea that’s a new idea, but it’s also based on something that he has some perspective and experience on.”

Schultz believes “when you join a Biden effort, you join the Biden family.” So does he feel pressure to protect the family brand?

“I’ve been around them for a long time,” he replied. “I think I’m a known quantity. I’d like to believe I work hard, and I’d like to think that’s rewarded in a Biden family, and I think it is. Actually, rather than pressure, I feel support, in particular, from Val. I think we have a very, very good relationship, and we’re very honest with one another. In terms of just the course of the campaign, there’s things that you kind of have to push through, and there’s things that you very much enjoy. I feel I can share both of those with Val.”

The Trump accusations about Hunter’s work for a Ukrainian gas company have been a particularly sensitive area to navigate.

“I think it’s hard for anybody to see their family under attack, especially the kind of attack Trump is waging,” said Bedingfield, the deputy campaign manager who oversees communications and, like Schultz, worked in Biden’s vice presidential office. “She’ll often call me and say, ‘Did you just see what so-and-so said? We’ve got to push back on this.’ In a good way. She channels the anger she feels about it in a real, productive way.”

The Hunter story — which will play out alongside an impeachment inquiry into the propriety of Trump’s efforts to persuade Ukraine and China to investigate a political rival — is one reflection of the way time, circumstance, and tragedy have changed Biden as a political figure. Beau “would have been right in the middle of this” campaign, former Biden aide Fran Person told BuzzFeed News. He was the heir to the political legacy. And his death — “Our child,” Biden Owens said with sadness in Beaufort. “His child. My child.” — changed the order of things. It kept his father from entering the 2016 race and forced a conversation about whether a Biden would ever be president.

What made the 1972 campaign work — and one of the enduring core values, even in the disappointing presidential bids — was Joe’s unshakeable trust in Val. (Kamala Harris, a Biden rival this time, joked about “fucking moving to Iowa.” During Joe’s 2008 run, Val actually did.) Joe never had to micromanage or involve himself in every decision. “Delaware’s a small state, and a lot of it’s personal, retail,” Kaufman, the longtime Biden adviser, said in a recent interview. “The most important thing to do is to be out pressing the flesh with the individual people. Joe Biden was never in the headquarters. Joe Biden was out every day, literally from morning to night, at a plant gate, or going to a coffee, or being at a supermarket. And then he’d come home — come back about 7, 8, 9 o’clock at night, he would sit down with Valerie, and they’d go over everything that happened through the day.”

Biden won that race by about 3,000 votes.

“Joe remembers everybody who voted for him,” Biden Owens said when recalling the win last month. “I remember everybody who didn’t. But that’s what a sister’s for, you know?” ●

Katherine Miller contributed to this story.