LORDSBURG, New Mexico — A young girl who was in the custody of US Customs and Border Protection went into cardiac arrest in November at a hospital in El Paso where she was resuscitated, a US Customs and Border Protection official told members of Congress on Tuesday.

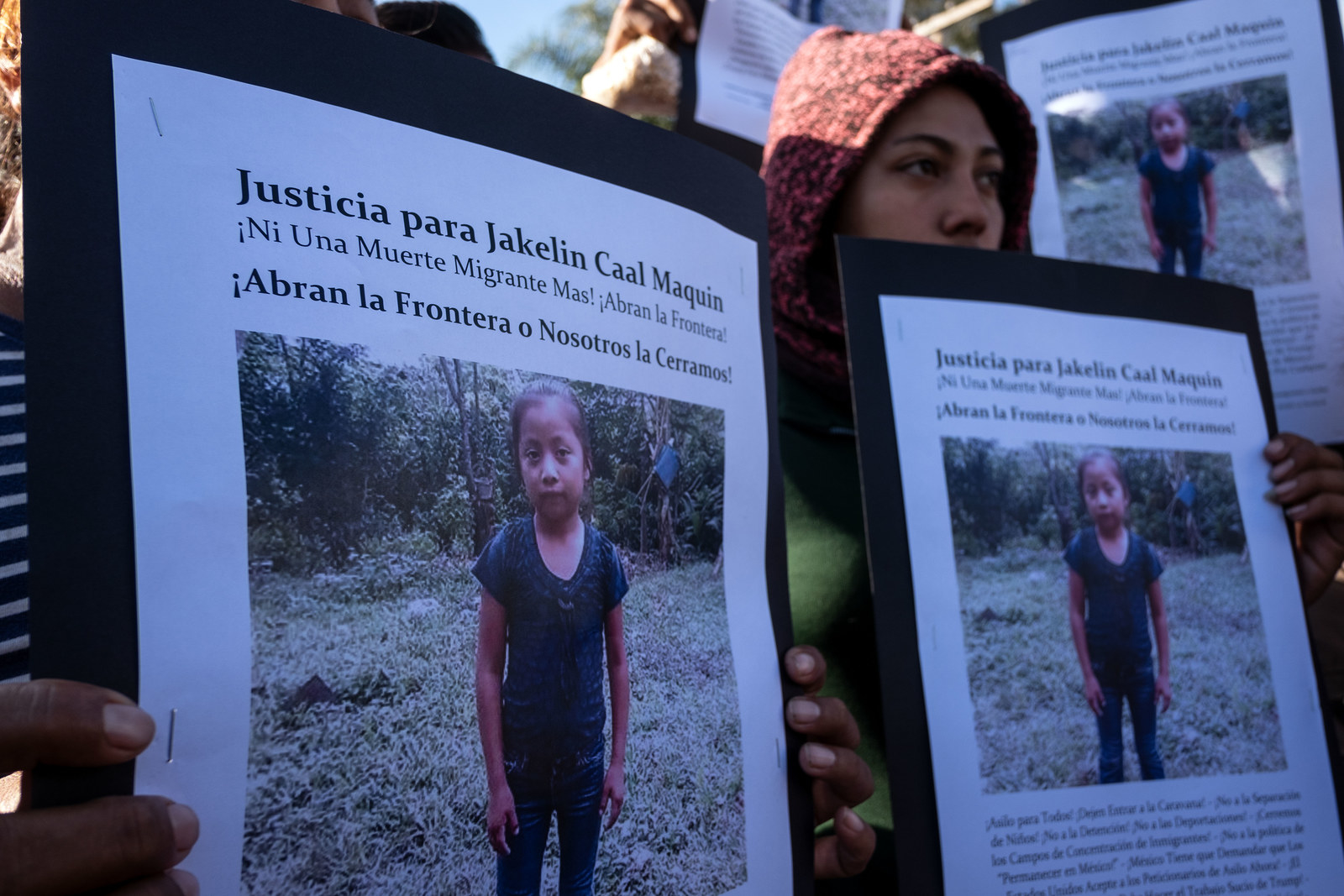

The incident occurred in the same CBP sector where a 7-year-old Guatemalan asylum-seeker, Jakelin Caal, fell ill earlier this month. Caal was airlifted to El Paso but died in the early hours of Dec. 8.

According to members of a congressional delegation that toured the CBP facilities where Caal had been held before her death, El Paso Sector Chief Aaron Hull acknowledged the earlier incident but declined to discuss the specifics of the case — or of several other alleged health crises involving children in the sector that were raised by the lawmakers.

According to a source present at the meeting, Hull said that while he’d have to review files on the case, he told the lawmakers that it was “lucky” doctors were able to save the girl’s life in November.

Following the tour, incoming Congressional Hispanic Caucus Chair Rep. Joaquin Castro of Texas said “it’s clear that for quite a while this sector has not been prepared to provide proper medical attention to people … like Jakelin. A lot of us left there wondering if there’re other cases of people who were close to death that we just haven’t found out about.”

Caal’s death has renewed focus on the administration’s increasingly heavy-handed immigration policies, including the use of so-called “metering” tactics at ports of entry that slow the processing of asylum request to a crawl, forcing thousands of families and children to wait for weeks to request asylum. On Tuesday, Castro called for CBP Commissioner Kevin McAleenan to resign.

Although details of the November case are scarce, they are similar to the Caal case. Both girls were taken into custody along the El Paso sector’s isolated western region in New Mexico, and both became sick while in custody. While Caal was taken directly to Hospitals of Providence Children’s Hospital when her condition became serious, the girl in the early November incident was taken to the hospital’s Transmountain Campus on the northern outskirts of El Paso.

Both girls “coded” — meaning their hearts stopped. Doctors at Transmountain were able to successfully revive the girl before transporting her to Children’s Hospital, where she made a full recovery. Although doctors were able to revive Caal multiple times, she ultimately died.

A CBP source Wednesday told BuzzFeed News that on Nov. 5th, a mother and her daughter were apprehended after crossing the New Mexico border, and were transferred to the agency’s facility in Deming, New Mexico. At approximately 3 pm, the mother informed agents that her daughter had a preexisting medical condition, and needed to see a doctor. CBP took the mother and daughter to the hospital in Deming, where doctors determined she needed specialized care, and she was then taken by ambulance to Providence hospital in El Paso.

According to this source, CBP has no further records on the girl’s health, although she has subsequently been released by CBP after she left the hospital. “That’s where our information drops off,” the source said, explaining that once a detainee is admitted to a hospital further information is not always entered into CBP’s data bases.

The CBP source pushed back against comparisons between the November incident and Jakelin Caal, arguing that while Caal stopped breathing — and was revived by CBP first responders — while in CBP’s physical custody, during the November incident “at no time [did] she have to be revived in our [physical] custody.”

A spokesperson for the hospital declined to provide further details, citing federal privacy regulations.

Whether there are more cases is unclear. Rep. Lou Correa, a California Democrat, told BuzzFeed News that “we’ve been told there’s at least four,” but that there were no details on those other alleged incidents.

Castro and other lawmakers said that during the tour it became clear that both the Antelope Wells Port of Entry, where Caal was originally detained, and the regional detention center in Lordsburg were completely unprepared to address even basic medical needs.

For instance, neither facility has an examination room or even an examination table — in Caal’s case, she was examined on a regular table. Neither facility had equipment tailored for use on children and neither had dedicated personnel who were trained in conducting physical examinations to assess detainees’ health needs.

Additionally, communication in Antelope Wells is extremely difficult — Border Patrol agents typically use cellphones to communicate, but there is no reliable cell service for more than 60 miles. That means agents addressing sick people in the field can’t even call a doctor to ask for help in determining if a person needs to be evacuated to a hospital, according to Rep. Raul Ruiz, a California Democrat who is also a physician.

Members of the delegation said that the Antelope Wells site also has major sanitation issues, including no running water and only two toilets for a detainee population that in recent months has numbered in the hundreds.

Those conditions also pose dangers to the CBP agents who are posted in Lordsburg and Antelope Wells: In fact, the building where immigrants are now housed was initially intended to be barracks for agents. “It’s also dangerous for the Border Patrol agents, and the administration is doing a disservice to them,” Castro said.

Rep. Al Green, who will chair the Financial Services Committee Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, agreed, telling reporters: “There are two sets of victims in this facility: the women and children who are here being processed, and the officers who are having to process them. They are both victims because to a certain extent these officers are doing what they are told, following rules, regulations, and orders, but it has caused them to be put in a position where they are hardening.”

Castro blamed the Trump administration’s focus on punitive deterrent and enforcement policies for what he said was a lack of resources CBP agents require to address the needs of children and other vulnerable people who seek asylum. “In not giving these agents the supplies and the equipment and the training they need to help someone like Jakelin … [President Trump] has allowed for these dangerous conditions that contributed to her death,” Castro told BuzzFeed News.

Castro and other lawmakers also argued the Trump administration’s policies are driving more and more immigrants into remote, and extremely dangerous, parts of the border like the New Mexico section.

The New Mexico border has traditionally seen little in the way of either irregular crossings or migrants coming to ports of entry to ask for asylum, in part because of its remoteness. At Antelope Wells, there’s no town, village, or even gas station. On the US side, the closest “town” is Hachita, which is 51 miles away and has a population of 49. The church in Hachita is abandoned, although there is a post office and a general store that also sells gasoline. Forty-eight miles south of Antelope Wells is the Mexican town of Janos, whose population of 2,738 people makes it a veritable metropolis in comparison to Hachita.

According to human rights activists who work with immigrants on the Mexican side of the border, there are no migrant shelters in the 260 miles that separate the Mexican city of Juarez, across from El Paso, and Nogales, the border city split between Mexico and Arizona. No nonprofit groups actively work in or monitor the region because border crossers traditionally have been so few.

While that isolation has made the area a favorite for drug smugglers, it has made it one of the last sections of the US border where migrants haven’t developed well-worn trails north. In fact, the traffic into New Mexico is so small, it is the only state on the southern border that does not have arrest and detention totals published by the Department of Homeland Security on a regular basis. No troops were sent to New Mexico when Trump ordered 5,900 active-duty troops to the border in late October, and none are assigned there now.

But in the last several months the number of migrants crossing along the New Mexican border has zoomed. While there are no hard numbers of people either being caught by CBP crossing irregularly or surrendering themselves to ask for asylum, Caal was part of a group of 163 migrants who crossed at Antelope Wells on Dec. 6, surrendering to Border Patrol officers.

And on Tuesday morning, a group of 200 asylum-seekers arrived at Antelope Wells, according to Castro, who said that CBP agents acknowledged “that for this area, and that for the more rural parts, that it’s an unusual occurrence.”

And it’s not just adults: Caal’s group included several families and as many as 50 unaccompanied minors.

The shift away from urban crossings like Juarez and Nogales appears to be part of a broader pattern that began earlier this year in response to President Trump’s family separation policy and a slowdown in asylum request processing at official border checkpoints. Human rights workers in Nogales said this summer that families were beginning to try their luck crossing the Sonoran desert — one of the most dangerous places — rather than wait in long lines at the border or risk having their children taken from them.

“One of the most dangerous effects of that Trump policy is that these folks, desperate and fleeing dangerous countries, among the most dangerous living conditions in the world, have decided to go around many of the urban areas and into the more remote areas of Mexico and the United States — which has presented even greater danger for them and their families,” Castro told reporters Tuesday.

The revelation of the rough conditions at the Antelope Wells station added to questions about what may have led to Caal’s death. Trump administration officials, in announcing the death, had said she had not eaten or drunk in several days and implied that she had walked through the desert to reach the US border.

But her father has told advocates in El Paso that she had been eating and drinking normally before she crossed the border and that they had taken buses to reach the US.

Adolfo Flores contributed reporting.