“The doctor said I have to take an antibiotic,” I tell my umma over the phone. “It’s like, um, that medicine that fights the bad things in your body,” I explain in my elementary Korean. My chest feels tight. Though I’m only five minutes into this phone call, my impatience at my inability to communicate my thoughts to my mom is quickly boiling over into a thick, internal rage. I take two deep breaths to settle my mind, and continue.

“It’ll make me feel good again,” I tell her.

And with that, I abruptly change the subject to something that requires less advanced vocabulary, so I can feel normal again, like my mom understands me, like I’m not a 27-year-old woman who doesn’t know how to talk to her own mom.

On the surface, my Korean isn’t that bad. To give you a sense of my proficiency, I can order extra kimchi at a restaurant, describe my plans for the evening, and talk about my job without giving away the least hint of amateurishness. What I can’t do is explain what said Korean food tastes like, describe the social dynamics between each of the friends I hope to see tonight, or explain the challenges of a company reorg.

But everyone knows relationships are built on subtleties, especially of the linguistic variety. And for every word or concept I can’t verbalize, I feel myself exhale-cry inside a little. I cherish my relationship with my parents, but it baffles me how we’ve gotten to this point with so many linguistic barriers. And it breaks my heart to realize that because of those barriers, our connection may never get any deeper.

Things weren’t always like this.

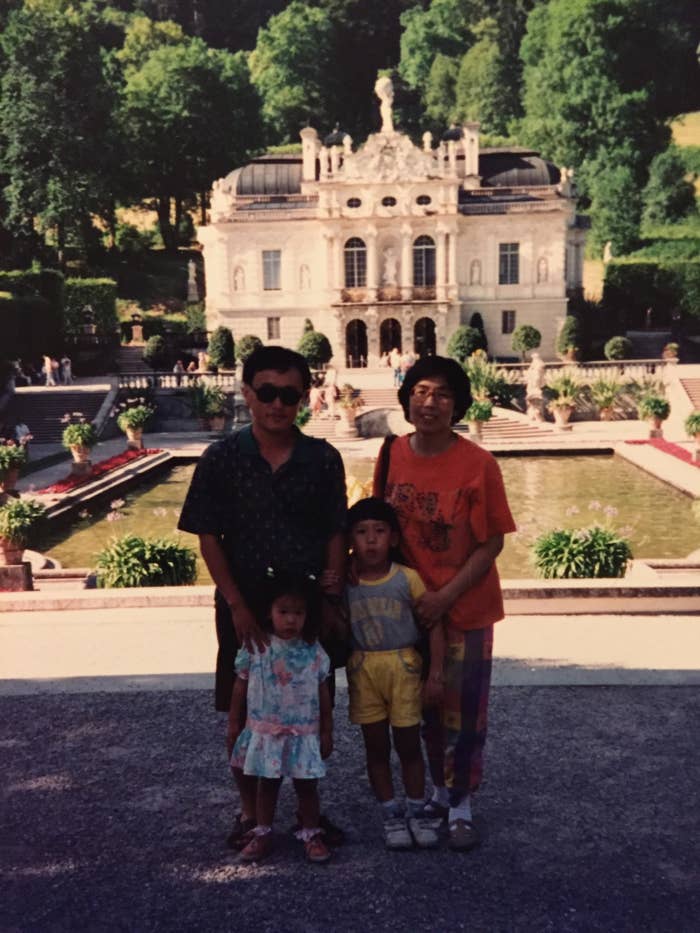

I grew up in Rome, and there, both my and my parents’ Italian was flawless. They had moved there in their twenties, to attend graduate school in two of Rome’s strongest disciplines — classical music and religious history. By the time they had me and my brother, they were fully assimilated to Italian life, and for the next 11 years, they raised me and my brother as Italian Koreans. It was only in 1998 that I realized how I had taken this cultural fluidity for granted. That’s when my parents made the decision to move the whole family to Los Angeles for better opportunities (which in our case was shorthand for, “the country you were born in will never legally recognize us as one of theirs, so”).

For my parents, moving was a deeply taxing thing: There were the obvious logistical challenges of trying to put down roots in a place that resembled nothing of our former home, but also the emotional challenge of trying to learn a new language at an age that no longer accommodated failure as mercifully as their twenties had.

For a second, I saw my mom how I’d like her to be — as someone perfectly apt at expressing her thoughts in a language I understood.

For a long time, every day was humiliating. Life was filled with labored interactions at the grocery store, at the DMV, at the optometrist. For my father, rock bottom probably happened the evening he opened a response from an office job he had applied to. He stood in the middle of his bedroom, frozen in fury, reading and rereading the letter that stated that no, they could not recognize his PhD, because it didn’t come from an accredited university, and that as consequence, no, they could not consider him for this role at this time. These days, my brother and I conjure up the scene of our dad violently crumpling up his degree whenever we want to evoke a feeling of pure anger and utter disappointment.

I got the chance to relive our former life when, in 2010, I went back to Rome to study abroad for a year. Seeing an excuse to vacation in their second homeland, my parents visited me for a week, tagging along as I took them on a tour of all my new favorite gelaterias, pizza al taglio shops, and vintage boutiques.

One Saturday, I took them to Via del Corso, a touristy boulevard lined with boutiques and designer shops. As most people who’ve traveled with their parents know, going shopping on holiday is pretty much the adult equivalent of throwing your favorite snacks into your mom’s grocery cart. I was psyched.

Passing by a glitzy Italian retailer, my mom and I saw our chance for brag-worthy swag and went in. We found soft scarves and plush sweaters for both ourselves and friends back home and proceeded to pay. The transaction finished without many words. Then, as my mom watched the cashier place our purchases in a pretty purple tote bag — you know, the reusable Lululemon kind — she interrupted with a question.

“So che questo è troppo da chiedere, ma potrebbe mettere i miei acquisti nelle buste separate?” (“I know this is a lot to ask, but could you put each of our purchases in a separate bag?”)

A full second of shock later, the cashier responded, “Mi dispiace, ma è la nostra regola; ci vieta a dare più di una busta per cliente.” (“I’m sorry, but it’s store policy that we only give one bag per customer.”)

For a second, I saw my mom how I’d like to her to be — as someone perfectly apt at expressing her thoughts in a language I understood.

I respect my mom more than any other person in the world. Every time I think back to the indignities she and my dad faced as adult immigrants in the US, all the thankless emotional labor she’s put in to secure my family’s happiness and financial stability, I feel the kind of reverence for my mom that many reserve for teenage heartthrobs or religious deities. But in that one moment in which my mom articulated her thoughts in perfect Italian, I felt such pride that thinking back on it now, I’m still filled with giggly admiration. It wasn’t so much that I was proud of her for the asking — more that she had done it in such a seamless way that gave away none of her foreignness.

Assimilation and its pursuit is toxic like that. It reduces your experience to “foreign” or “one of us,” violently crumpling and tossing into the former bin all the things that don’t quite fit.

The worst part was, I couldn't even help the feeling of pride as my mother spoke the mother language fluently. In a country gamed for the success of the assimilator, it takes little time to change loyalties.

It's impossible not to hear how childishly self-centered I’m starting to sound, though: Of course, the voice missing from this entire story is that of my parents. I cannot fathom the frustration they must feel at the disconnect between their lives and the Americanized experiences of their children.

No parent wants to not understand their children. But my parents did want to secure my happiness more than they did their own.

Every time I bring up my frustrations with trying a new soup recipe — much less explaining a medical malady — my mom pauses the conversation to guess at the meaning of every other word. A mom’s patience might be an impressive skill, but I’ve come to consider an immigrant mom’s patience as a holy thing.

The technical repercussions of this linguistic barrier are even more pronounced for my dad, who, while one of the most competent and senior persons in his office, has yet to be promoted to a managerial role because he continues to fail the verbal interview part of the process. His English is professional, but it is at times grammatically rough and peppered with awkward pronunciations. Which all give away the fact that, as a result of his international schooling, English is, indeed, his fourth language (after Korean, Spanish, and Italian).

My brother and I have never been able to fully communicate the nuances of our lives to our parents, and until our twenties, our parents never actually told us — verbally — that they loved us. As I've learned, though, there are a lot of ways to show you care about someone, and “I love you” is often the least meaningful one. We never once felt unloved.

Jenny Zhang best summed it up for all of us in a 2017 episode of Another Round, when she said, “Part of them loving me is accepting that they have released me to be someone they can’t understand.”

Like Zhang, I’ve also begun to accept our linguistic confusions as an extension of my parents’ love. Because no parent wants to not understand their children. But my parents did want to secure my happiness more than they did their own.

I’ve been trying to teach myself German these days. I’m traveling to Berlin in a month, and thought it might be useful to learn at least the basics. But it’s proven harder than I thought, especially with a full-time job, a social life, and a lack of the kind of time it takes to essentially learn a new way of making your brain synapses process information.

I figure, though, that my parents bought a home, found jobs, and raised me and my brother using their “broken" English. So I think I’ll manage being a tourist for a week. ●