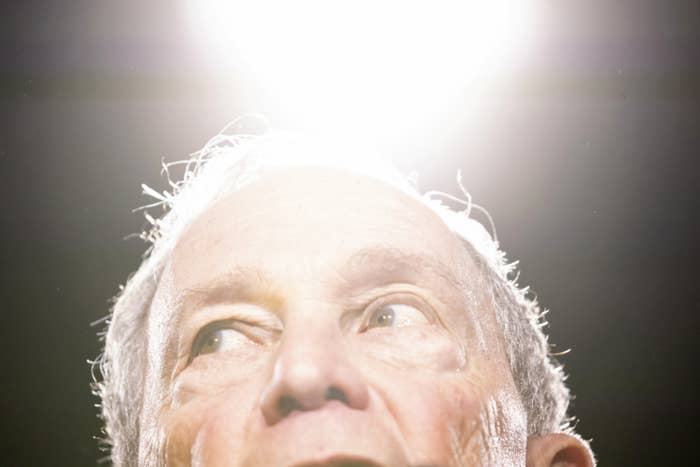

RALEIGH, North Carolina — Michael Bloomberg is not a tall man. But his presidential campaign is very big.

The sheer hugeness of the former New York City mayor’s campaign is its defining feature. It is the Death Star of presidential campaigns. Bloomberg employs more — much more — staff than any other candidate and pays them unusually well. And not only that, he offers them three meals a day and iPhone 11s. Bloomberg’s campaign events have everything: catered food, more than enough free T-shirts for everyone, highly produced stages with themed backdrops and lecterns. Bloomberg is carrying out the largest advertising campaign in the history of American presidential politics, with over $400 million spent on ads so far and counting. Bloomberg is cornering the market on available staff for other campaigns that might need them.

Bloomberg’s campaign is like a giant lava cake that has oozed across the plate, the plate in this case being the United States. While the other Democratic candidates schlepped all over Iowa and New Hampshire, shaking hands in coffee shops and holding town halls in Elks lodges, Bloomberg was jetting around states that vote later and attracting large crowds; a move that looked particularly smart after the Iowa caucuses fiasco. Bloomberg’s advertising has raised his profile such that, though he did not contest New Hampshire and wasn’t on its ballot, Bloomberg won thousands of more votes in the state’s primary than two candidates who had pinned their entire hopes on the state. It’s probably not a coincidence that Bloomberg has been advertising heavily in neighboring Massachusetts, which votes on Super Tuesday, when more than a third of pledged delegates will be up for grabs across 16 contests. Bloomberg is simply everywhere.

The overwhelming size and scope of Bloomberg’s campaign is more than a gimmick: It’s a validator for more moderate Democrats looking for a stable home in a tumultuous primary, a signal that while other candidates may stumble in the primary or later against President Trump, Bloomberg’s operation is too big to fail.

The Bloomberg strategy is to vacuum up delegates from states that offer many of them, instead of scrabbling to win the delegate-poor early states. The campaign is focusing now on the Super Tuesday states, which vote on March 3. Though Bloomberg’s name won’t appear on a ballot until that day, he’s become an increasing presence in the race. Everyone is suddenly talking about Bloomberg.

There are a few reasons for this; for one, former frontrunner Joe Biden is slumping, and voters who want a moderate candidate are searching for alternatives. For another, more and more polling shows he’s competitive nationally. And Bloomberg has been announcing more and more high-profile endorsements — sometimes, from political figures to whom he had generously donated in the past or supported causes connected to them.

Bloomberg’s debut as a serious candidate has prompted a reckoning with his record, and this past week, as Bloomberg was blitzing Super Tuesday states, was tough going. Audio of remarks Bloomberg made at the 2015 Aspen Institute conference surfaced in which Bloomberg defended his mayoral administration’s policy of heavily policing black neighborhoods using stop-and-frisk, arguing that “minority neighborhoods” have more crime and making derogatory comments about young men of color.

More allegations from Bloomberg’s past have come to the fore. A Washington Post story published over the weekend delved into serious allegations of sexism from Bloomberg employees. The paper also published “The Wit and Wisdom of Michael Bloomberg,” a collection of sexist quotes attributed to Bloomberg that was given to him as a birthday gift in 1990.

But so far, Bloomberg is exhibiting a Trump-like Teflon ability to brush off the negative stories. Part of this could be because a lot of what’s coming out now has been in the public record for some time; like Trump, Bloomberg has been a public figure for decades, and much of his history has been litigated before, particularly in his three mayoral campaigns. Part of it could be due to his ability to buy himself positive media in the form of advertisements; he isn’t dependent on earned media to define himself in voters’ minds. And part of it could be because, as became clear in the last presidential election, voters with a goal in mind often don’t care about the issues with a candidate that the media cares about.

Welcome to the Bloomborg. Resistance is futile.

When I arrived at the Bessie Smith Cultural Center in Chattanooga, Tennessee, the day after the New Hampshire primary, a line was already forming to get in to see Bloomberg an hour before his event’s 2 p.m. start time. Outside, a young woman with a septum ring was handing out pro-Bernie Sanders literature. Her name was Katie Keel and she was a cochair of the local chapter of Democratic Socialists of America. I asked Keel whether Bloomberg was substantively worse, in her view, than the other moderate candidates like Biden or Pete Buttigieg.

“Yeah, he’s a billionaire,” she said. “First of all, he shouldn’t be a billionaire in the first place. Bernie Sanders would agree, billionaires shouldn’t exist. So we're out here to protest that, just saying that you know what, I don't care if you're only one person, you can't throw unlimited amounts of money at the election, you can't buy it, it shouldn't be allowed.”

DSA members are about as far away as one could get from Bloomberg supporters on the Democratic Party’s ideological spectrum, but even they had not been untouched by the campaign’s push in their state. Keel’s DSA colleague Jefferson Hodge mentioned that he knew five or six people in local Democratic politics who had been offered gigs by the Bloomberg campaign at around $8,000 a month; Hodge said he would no longer call them friends. Organizers earn $6,000 a month, though “If they're up at a higher level in the organization [it] could be more,” a Bloomberg aide said.

A few yards away from the young DSA activists stood Mitchell and Robin Beene, 64 and 62, Chattanooga residents who had come out to see Bloomberg.

“We really want to defeat Donald Trump,” Mitchell Beene said. He said he leans “very far left, and in a perfect world I might like Bernie and Elizabeth Warren.” But “practically, I just think that Donald Trump would be extremely afraid of Mike Bloomberg.” The Beenes said they were still undecided but would probably vote for Bloomberg when Tennessee votes as one of the Super Tuesday states.

They were far from the only voters I spoke with who said some version of this; nearly everyone I spoke to at Bloomberg events over the past two weeks said their top priority was beating Trump, and they believed Bloomberg could do it.

This directly echoes Bloomberg’s own pitch, which is that he alone is prepared to take Trump head-on, isn’t afraid of him, and will use the full weight of his enormous resources against him.

In Chattanooga, Bloomberg’s campaign had chosen a venue that was much too small for the number of people who showed up. The clever optics resulted in a large overflow crowd outdoors. Campaign people threw T-shirts to them as they waited. When Bloomberg arrived, he stepped onto a platform, got on a microphone amplified by large speakers, and said he was “embarrassed” that they didn’t have enough room for everyone. He encouraged those waiting to go home if they were cold, the campaign would send them the speech later — he didn’t want them to catch the flu.

He then went inside to give his speech.

While Bloomberg’s campaign is huge, his stump speech is very short. It usually clocks in at under 15 minutes. It usually begins with a joke about how whichever surrogate gave his introductory speech delivered their remarks “exactly how I wrote them.” During a stump speech, Bloomberg is likely to describe himself as the “un-Trump” more than once. He doesn’t mention his rivals for the nomination beyond oblique references to “evolution not revolution.” Apart from remarks like that, Bloomberg’s campaign is fiercely nonideological. He only really talks about Trump, and how he is running to defeat him. He warns darkly that four more years of Trump would be “hard to recover from.” That said, Bloomberg did take a shot at Sanders on Twitter on Monday, posting a video comprised of aggressive tweets by Sanders supporters superimposed over ominous music.

More often than not, there’s a protester in the crowd; in Chattanooga, a woman came onstage at the beginning of the rally, got on the microphone, and said, “This is not democracy. This is plutocracy.” In Nashville, one protester shouted that Bloomberg “brags about terrorizing innocent youth,” and another waved a pair of handcuffs.

Bloomberg greets the protesters with equanimity, often joking that they make him feel at home. To the man with handcuffs, he said, “We’ll get back to you later.”

Bloomberg wraps up his speech, walks offstage, greets the audience for a few minutes, and leaves, to the tune of “Beautiful Day” by U2. Bloomberg hasn’t done a townhall-style event yet, where he’d have to take more questions from the audience, and he doesn’t do much retail politics. He sticks to prepared remarks apart from a stray comment here and there, including a couple of tangents about his supporter Judge Judy during the North Carolina swing and the occasional, sometimes strange, ad-lib. For example, in Greensboro, Bloomberg punched back at Trump’s taunts about his height; Trump has branded him “Mini Mike.” “My answer is Donald, where I come from, we measure height from the neck up,” Bloomberg said. Bloomberg seemed to be making a reference to intelligence, but the phrase conjured an unsettling giraffe-like image.

In Chattanooga, Bloomberg was to conduct an interaction with the press that his staff described as a “gaggle.” The term normally connotes a casual interaction with the reporters following a campaign, who will gather around a candidate, stick their recorders in his or her face and carry out a relatively freewheeling exchange. This gaggle was different. A lectern with microphones and campaign signage had been set up. Four American flags were displayed behind it. As staff herded reporters into a specific configuration — print reporters were at first sent behind the TV cameras before being allowed to squat in front of them — another, even larger flag was erected off to the side. We were given two-minute, 90-second, and 30-second warnings before Bloomberg entered. The press corps following Bloomberg has swelled; initially he was being trailed by only a couple network embeds, but now every major outlet is sending reporters on his trail.

Reporters pressed Bloomberg multiple times about the Aspen Institute remarks, which he did not take the opportunity to apologize for.

“It was five years ago,” Bloomberg said. “It’s just not the way that I think and it doesn’t reflect what I do every day. I led the most populous, largest city in the United States and got reelected three times, the public seemed to like what I do."

When a reporter asked him if the issue would harm his chances with black voters, Bloomberg said, "I think people look at it and they say those words don’t reflect Michael Bloomberg, the way he governed in New York City, the way he runs his company, the way his philanthropy works."

Bloomberg has made a concerted effort to court black voters, and there are signs that it’s working. A national poll from Quinnipiac last week had Bloomberg trailing only Biden among black voters. Particularly among older black voters I spoke with — a key demographic on which the Biden campaign is counting for support — there’s a sense that Bloomberg is best equipped to defeat Trump, and several said they found Bloomberg’s apology for stop-and-frisk at the start of his campaign sufficient.

No black voters I spoke with at Bloomberg events said they were troubled enough by the former mayor’s record on race to not vote for him.

“He apologized,” said Robert Lewis, 73, of Chattanooga. “And we have a man in the White House now who don’t apologize for nothing.”

Stop-and-frisk “was very bad,” said Butler Benton, 69, who attended Bloomberg’s event on Thursday in Raleigh and said he made up his mind to support Bloomberg three or four weeks ago. “But, you know, nobody has clean hands.” Benton argued that Bloomberg’s record wasn’t worse than some of the other candidates’.

“Now, we can talk about stop-and-frisk,” Benton said. “You can talk about Biden eulogizing Strom Thurmond. You can talk about Biden coalescing with segregationists to defeat cross-district busing. You can talk about him being an accomplice in the assassination of Anita Hill.”

The dynamic — a media storm over an issue that voters don’t find dispositive — reminds those of us who covered the 2016 Republican primary of a certain other candidate.

The next morning in North Carolina, Bloomberg’s venue for his first of three events in the state that day was beginning to fill up. The event’s start time was 7:30 a.m., and it took place at a local coffee shop; the exhausted press corps arrived a half-hour in advance and slumped over laptops in the back, watching with increasing surprise as the room filled up to capacity and overflow had to be sent next door to a connected brewery. The campaign said an estimated 500 people came, and 200 in the overflow, and that they had had to change venues because of all the interest.

Mark Stoehr, 69, from Kernersville, sat in the back. “I’d like to see Mike,” he said. “I think he’s got the best chance of beating Trump. I don’t like any of the other ones.” For Stoehr, “Biden’s got too much baggage, and I don’t think Buttigieg can get enough support.”

Stoehr said he had found out about Bloomberg through the ads Bloomberg has been airing in North Carolina, and “I like what I see.”

Jackie King, 64, from Burlington, saw Bloomberg at his Greensboro event later that morning. She, too, had been bombarded with Bloomberg’s advertising. “Oh my gosh, he’s running them on Animal Planet,” she said.

Biden, King said, “just doesn’t seem to have the momentum. But I think Bloomberg has it, and he’s got the money and he’s got the gravitas.”

King, like many other voters I spoke with, is completely unbothered by Bloomberg using his riches to get a leg up in the contest.

“If anything, he’s not having to pander to anybody,” she said. “That never really occurred to me. I’m aware of it, but it’s not a factor in whether I like him or not.”

This, again, is an issue that might seem like a bigger deal on Twitter than it is to many of the people who are going to decide this election. Many Democrats will do anything to get rid of Trump, and to them, Bloomberg’s resources and the vastness of his campaign are a plus. They don’t want anything to do with an ideological battle over the future of the Democratic Party; they want Trump gone, and they want someone who will stand up to Trump. Bloomberg’s appeal echoes this. He constantly emphasizes that he won’t let Trump “bully” him, that he’ll “take the fight to Trump,” and he’s willing to get down in the muck and trade insults with Trump on Twitter. (Getting on Trump’s level, for what it’s worth, is a tactic that has been tried by previous Trump opponents and did not work).

But Bloomberg’s strategy has never been tried before, and if he does manage to box out the other moderate candidates through sheer gigantism he’ll soon have to contend with Bernie Sanders, the Democratic frontrunner, and his army of supporters. We might get a preview of how this will play out as soon as this week; Bloomberg is within one qualifying poll of appearing in Wednesday’s debate in Nevada.