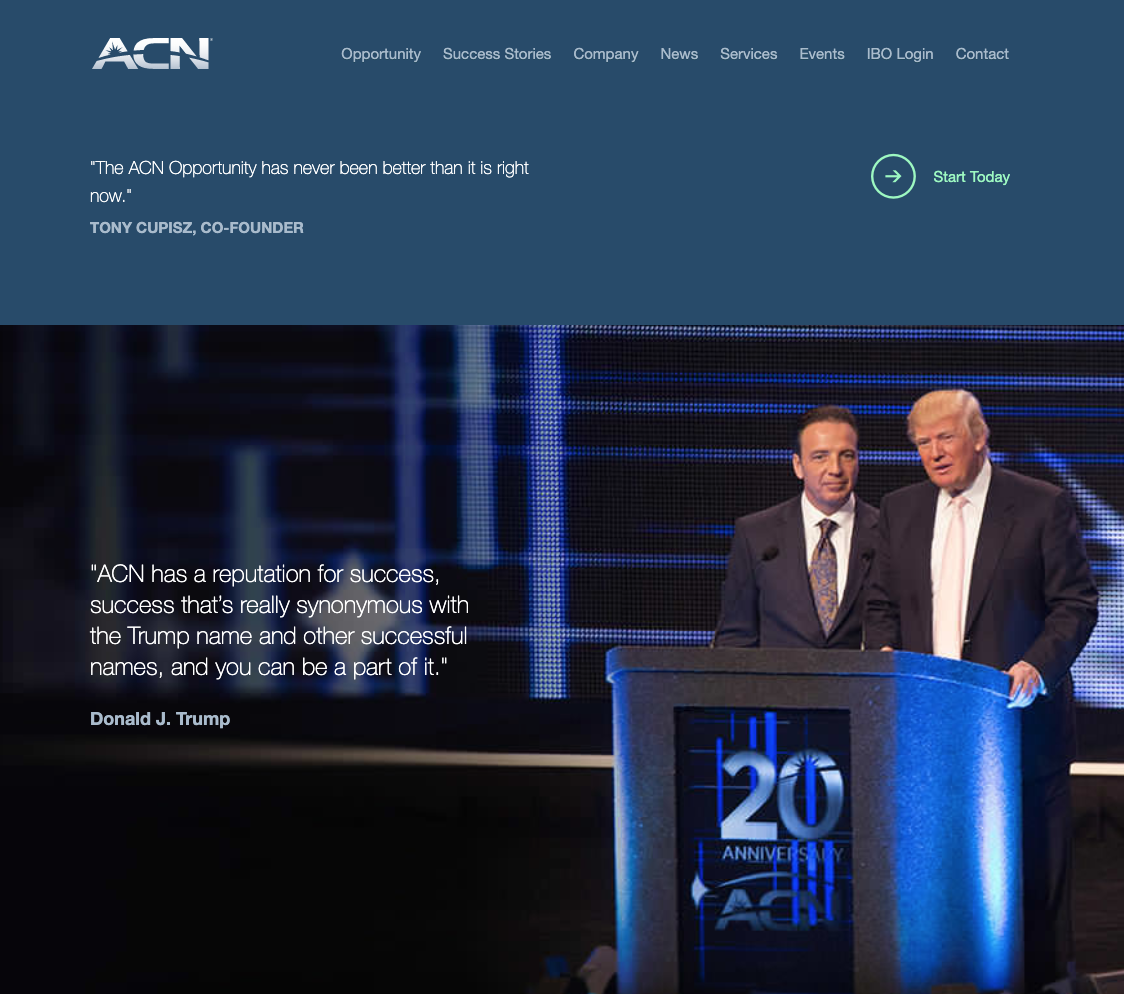

WASHINGTON — Jane Doe, a hospice worker from California, was still undecided midway through an investor recruitment meeting in 2014 for a multilevel marketing company, ACN. But the promotional video she watched featuring Donald Trump — still in the midst of his run as star of The Celebrity Apprentice — won her over.

Trump’s assurances that ACN was “one of the best businesses” were convincing. He already had so much money, Jane Doe told herself, he wasn’t trying to scam her. She paid the $499 registration fee. She spent thousands of dollars attending ACN conferences, hosting recruitment events to sign up other investors, and attending local meetings, all while trying to sell ACN’s video conferencing and telecommunications products.

In the end, according to a lawsuit Jane Doe and other aggrieved ACN investors filed under pseudonyms against now-president Trump last year, she received one check. She earned $38. The investors are accusing Trump — who appeared in multiple promotional materials for ACN and spoke at the company's investor conferences — of fraud. They claim that he falsely touted ACN as a profitable and low-risk investment, even though he knew or should have known it was a bad investment, and that neither he nor ACN disclosed that he was being paid to endorse the company.

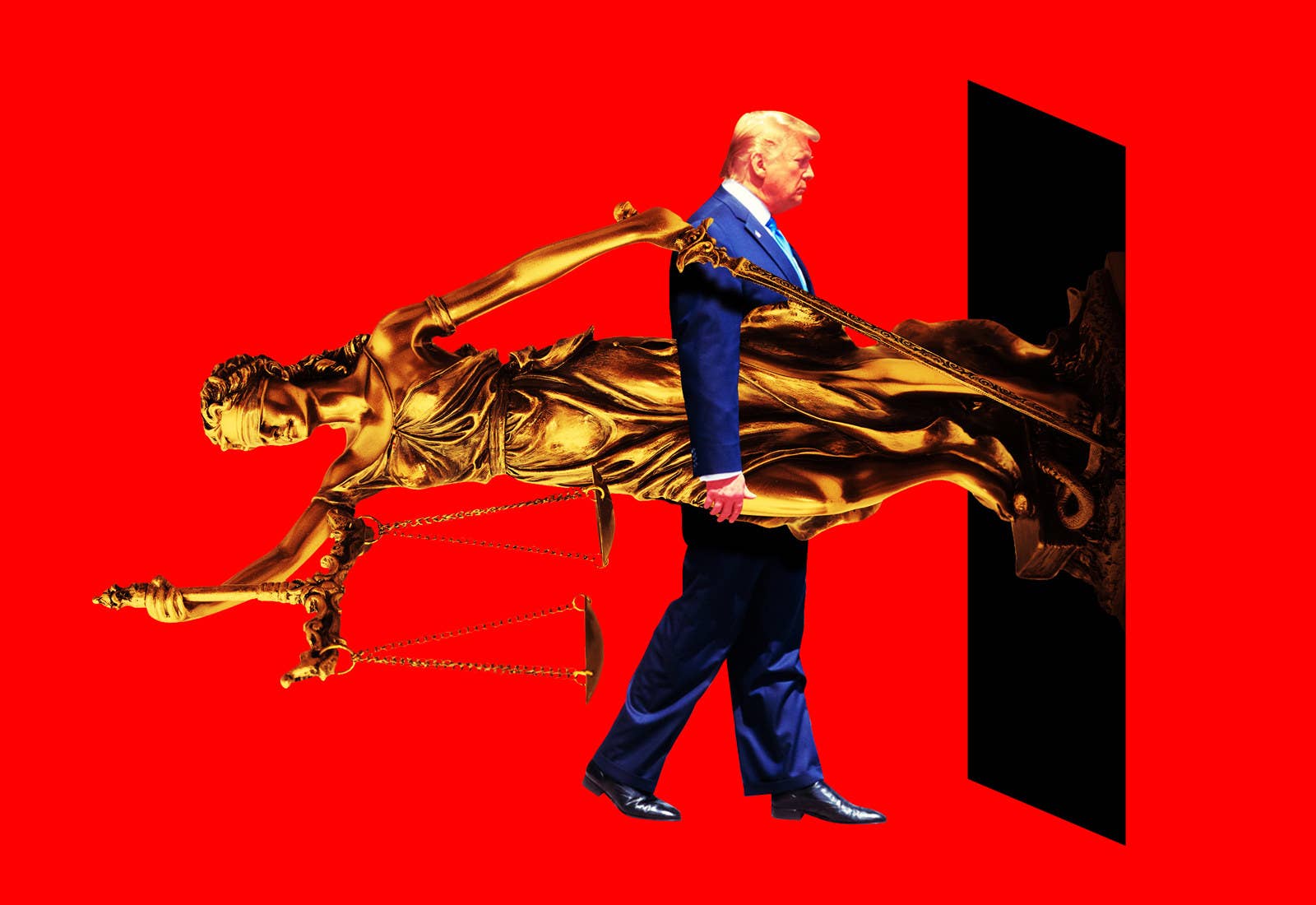

Jane Doe now finds herself in a situation familiar to Stormy Daniels, former Trump campaign and White House staffers, employees who worked for Trump’s companies, and investors who put money into his businesses: Trump is arguing to move the lawsuit out of court — where evidence, arguments, and hearings generally are a matter of public record — and into the more secretive private justice system he has used for more than a decade to keep these kinds of unflattering allegations quiet, known as arbitration.

“Trump’s kangaroo court, that’s what they are.”

Of the thousands of lawsuits filed by or against Trump and his companies over the years — a USA Today investigation identified at least 3,500 cases — the vast majority have played out in court. But in a small number of cases in which Trump, his 2016 campaign, or his businesses have been accused of discrimination, shady business practices, and other bad acts, the president and his lawyers have invoked clauses in contracts that give them the power to force these disputes behind closed doors.

Unlike in court, the public and the media don’t have a right to observe arbitration hearings or to see documents. Arbitration critics also say the system disadvantages employees and other individuals who sign away their right to the public justice system via agreements they typically have no role in drafting.

“Why does Trump want arbitration? Because he wants to control information,” said Yale Law School professor Judith Resnik. “The key thing they’re shopping for is confidentiality.”

Resnik said there are often fewer resources available to people in arbitration who can’t afford a lawyer than in the courts. The party that writes the arbitration clause — for instance, Trump’s campaign or businesses — can also shape many of the rules for how a case will unfold in their favor, she said; the rules for how a lawsuit works are public and set in advance by the court.

Sam Nunberg, a former Trump campaign adviser who was briefly embroiled in an arbitration fight with Trump in 2016 that they eventually settled, told BuzzFeed News that he felt he was at a disadvantage in a system that Trump was more familiar with.

“I don’t want to go to arbitration. Arbitration is expensive. … It wouldn’t have been a fair venue for me against someone like Donald Trump who brings everything to arbitration. They’re never going to rule against him,” Nunberg said. “Trump’s kangaroo court, that’s what they are — the way they acted, at least with me.”

Trump’s lawyers in recent cases that went to arbitration did not return requests for comment; neither did his 2020 campaign or an attorney for the Trump Organization.

One-Sided Agreements

Until the 1980s, arbitration was mostly used by companies that didn’t want to hash out disputes involving business practices and trade secrets in public. In the decades since then, the US Supreme Court has issued a string of decisions upholding the lawfulness of contracts with mandatory arbitration clauses, like those used by Trump, that cover a wider universe of situations in which a person might want to bring a claim against a company. This shift is part of a broader trend of more business-friendly decisions from a court that’s grown increasingly conservative, including under Trump.

Arbitration clauses are now in everything from credit card contracts and employee hiring agreements to Uber’s user terms of service. Unlike company-versus-company cases, which tend to involve well-resourced and heavily lawyered corporate actors who come into arbitration on an even playing field, consumer and employment agreements normally aren’t the product of negotiation. Whoever downloads an app on their phone, signs a hiring contract, or invests in a multilevel marketing company backed by a wealthy television personality is presented with terms the company came up with.

“The idea that arbitration is an easily accessible system for consumers is belied by the fact of how many people use it,” Resnik said.

Trump’s forays into arbitration over the past decade underscore complaints consumer advocates have about the modern state of the system. Some of these cases involve agreements that Trump’s 2016 campaign or his companies crafted unilaterally and presented to people who applied for jobs. Once the disputes were moved to arbitration, the proceedings became secret.

The ACN investors’ lawsuit presents a new twist. Trump’s lawyers said in a July 19 court filing that they planned to argue the case should go to arbitration even though Trump wasn’t named in the contracts that investors signed with ACN and he didn’t sign them. Neither did the Trump Organization, Ivanka Trump, Donald Trump Jr., nor Eric Trump, who were also sued for their alleged role in promoting ACN.

Trump’s lawyers are arguing that the president can still invoke the arbitration clause because any claims against him as ACN’s “paid spokesman” were “intertwined” with the ACN agreement.

But the investors want their case to stay in the public record in court. They counter that Trump waited too long to try to force arbitration and, regardless, he isn’t covered by the contract. A key part of the investors’ case is that they claim no one told them Trump was being paid by ACN, so they couldn’t have intended their contract with ACN to apply to Trump, attorney Roberta Kaplan argued in a July 18 letter to Trump’s legal team that was filed in court. Kaplan declined to comment, and Trump’s lawyers didn’t respond to an interview request.

“In light of these allegations, it is non-sensical […] to surmise that when Plaintiffs came to a meeting of the minds with ACN, they believed they were also constraining themselves as to the Trumps,” Kaplan wrote.

The investors’ case in some ways mirrors the experience of Stormy Daniels, the adult film actor who took a $130,000 hush money payment orchestrated by Trump’s former lawyer Michael Cohen so she wouldn’t go public with claims of an affair with Trump. In March 2018, Daniels sued Trump and Essential Consultants LLC — the company Cohen set up to facilitate the payment — challenging the validity of the hush money agreement, which included an arbitration clause that Cohen had tried to invoke.

A month later, Essential Consultants, joined by Trump, asked a federal judge in California to move the case to arbitration, citing the hush money agreement. Daniels objected, arguing Essential Consultants wasn’t a party to that contract and Trump never actually signed it. The case was put on hold while Cohen faced criminal prosecution. Trump then came forward with an agreement that he wouldn’t try to enforce the nondisclosure agreement, and the parties are now litigating over whether that was valid and if it makes the case moot.

Daniels’ lawyers and lawyers for Trump and Essential Consultants did not return requests for comment.

The plaintiffs in the ACN case aren’t the first investors to put money in a Trump-affiliated business and then face an arbitration demand after trying to sue.

In 2008, investors who put money into the Trump International Hotel & Tower in Las Vegas sued the company, claiming they were defrauded. They alleged that sales representatives misled them about the value and risks of the investment in part by assuring them that the project would be profitable because of the “Trump brand.” In another, related case, investors accused Trump himself of falsely pushing a message to the public that the condos were selling fast in order to “manufacture a purchasing frenzy.”

All of those claims landed in arbitration, and the investors lost — in one case an arbitrator ruled the investors couldn’t go forward as a class action, and in another an arbitrator dismissed the claims outright. They unsuccessfully challenged arbitration decisions in court, and the disputes ended in confidential settlements. Lawyers for the plaintiffs and for the Trump project did not return requests for comment.

In the ACN case, Trump lost an early attempt to get the case tossed out of court. On July 24, a federal judge in Manhattan dismissed the investors’ racketeering claims against Trump, finding that they hadn’t shown that his actions were directly related to their financial losses through ACN. But she allowed the fraud claims to go forward.

The judge is expected to take up the arbitration issue this fall.

Layers of Secrecy

In arbitration, a neutral third party — paid for by one or both of the parties — considers evidence and arguments and decides who wins. The proceedings are generally private and the decisions are meant to be final. Under federal law, the courts can only intervene in cases where an arbitrator was clearly corrupt or biased, or if an award represented “manifest disregard” of the law, which is a high bar.

In 2013, former Miss USA contestant Sheena Monnin unsuccessfully tried to challenge an arbitrator’s decision awarding the Trump-backed pageant $5 million after finding she’d defamed the organization with claims that the contest was rigged. The Miss Universe organization went to court to enforce the award, and Monnin argued that the arbitrator exceeded his power and showed a “manifest disregard” for the law. She also argued that her lawyer never told her about the arbitration proceedings and she never got notice directly from the arbitrator. Monnin lost, although the judge noted she’d suffered in part from a “poor choice of counsel.”

“The Court does not take lightly that Monnin is compelled to pay what is a devastating monetary award,” the judge wrote in a July 2013 opinion. “That being said, a court’s role in reviewing an arbitration award is necessarily limited. […] Sympathy, or apparent inequity, may play no role in a court’s legal analysis, and here, the law is clear.”

Trump’s 2016 campaign used arbitration clauses to build a second layer of secrecy into unusually broad nondisclosure agreements signed by some staffers. They had to pledge not only that they wouldn’t share confidential information — something other campaigns have done in the past — but also that they wouldn’t “demean or disparage publicly” Trump, his company, or his family members and their companies.

The NDAs featured a clause giving Trump, his campaign, and his family the sole power to decide if grievances raised by his campaign staffers should go to arbitration. The agreement also said that Trump kept the right to bring cases in court, a right not afforded to his campaign staff.

One former Trump campaign staffer, Jessica Denson, is challenging those NDAs. She filed a lawsuit in state court in New York in November 2017 accusing the campaign of discrimination and a hostile work environment. While her state court case was pending, the campaign went to arbitration, arguing that Denson’s lawsuit violated her NDA. She filed another lawsuit in March 2018, this time in federal court, arguing that the NDA itself was invalid. The judge granted the campaign’s request to move that case to arbitration.

An arbitrator concluded that Denson violated her NDA and awarded the campaign more than $52,000. She went back to state and federal courts to challenge the award. She lost and is now appealing, and also arguing to stop the campaign from enforcing the award in the meantime. Her original claims against the campaign are pending; the state court judge previously ruled the NDA didn't cover her employment-related allegations.

After repeatedly having her claims moved out of court, when Denson decided to file a class action challenging all of the campaign’s NDAs, she went straight to arbitration. In late May, however, the campaign said they would not agree to arbitration, according to emails reviewed by BuzzFeed News, which meant Denson’s next option was to bring the case in court — putting her back where she started. In a letter to the American Arbitration Association last month, Denson’s lawyers accused the Trump campaign of engaging in an “unrelenting effort to prevent any tribunal from making a decision on the NDA’s validity.”

In a statement to BuzzFeed News, Denson said the campaign “has attempted to use an illegal and unconstitutional arbitration agreement to attack my rights as a free American, a clear example of the threat on our democracy.” Denson’s lawyer David Bowles declined to comment on what they would do next, but in an interview he reiterated their original preference for a public airing of Denson’s claims.

“I always tell my clients to rip those clauses out of agreements.”

“I always tell my clients to rip those clauses out of agreements at every chance possible because they are giving up a very fundamental right of American justice which is due process,” Bowles said. “You’re getting secrecy and you are getting a lack of precedent. And those are not advantageous to the public, to employees or to consumers.”

Trump has brought arbitration cases against two former White House staffers, Omarosa Manigault Newman and Cliff Sims, both of whom wrote tell-all books about their time in the Trump administration. Sims, who worked on Trump’s campaign before going to the White House as a communications aide, filed a lawsuit in February after the campaign filed an arbitration demand accusing Sims of violating a nondisclosure agreement.

Trump is now arguing that an arbitrator, and not a judge, should decide whether Sims' challenge to the NDA's arbitration requirement should itself play out in arbitration. A federal judge in Washington is considering putting the case on hold, however, until an appeals court resolves pending questions in other cases about when judges can enter orders against a sitting president.

The campaign filed a similar arbitration proceeding against Manigault Newman, who also worked on Trump’s campaign before going to the White House. She hasn’t brought a challenge in court, and her lawyer didn’t respond to a request for comment about the status of the arbitration.

A spokesperson for Trump’s 2020 campaign did not return a request for comment on whether they’re having staffers sign any agreements now that include arbitration clauses.

In May 2016, Trump’s campaign filed an arbitration demand against Nunberg, whom Trump accused of leaking confidential information about the campaign — including, for instance, about a reported fight between then–campaign spokesperson Hope Hicks and then–campaign manager Corey Lewandowski — in violation of a nondisclosure agreement. The arbitration didn’t become public until July 2016, when Nunberg went to court to challenge it.

Nunberg’s lawyer argued that the only agreement Nunberg signed with any connection to the 2016 campaign didn’t provide for arbitration. Nunberg signed an earlier political consulting agreement with Trump in 2011 and 2012, according to his court papers, and that included an arbitration clause.

A month after Nunberg filed suit, he dropped the case, and Nunberg’s attorney told reporters that the fight had been “amicably resolved” but didn’t offer any details. In an interview with BuzzFeed News, Nunberg declined to comment on the terms of the settlement.

“Less Voluntary, Less Consensual”

A few employees of Trump’s businesses have also seen their claims taken out of court and moved to arbitration in recent years. In July 2018, Noel Cintron, who had worked for Trump and the Trump Organization for more than two decades, including as Trump’s personal driver, filed a lawsuit claiming thousands of hours in unpaid overtime. Trump’s lawyers invoked an arbitration agreement that Cintron signed. In late August 2018, Cintron dropped the lawsuit and the case went to arbitration.

Cintron’s attorney Joshua Krakowsky confirmed to BuzzFeed News that the arbitration case is pending, but otherwise declined to comment. Trump’s lawyer did not return a request for comment.

In September 2017, a group of current and former employees of a restaurant in the Trump International Hotel in Washington, DC, BLT Prime, filed a racial discrimination lawsuit against the hotel. The case included allegations that black and other minority workers were denied more lucrative shifts, ordered to adopt “Caucasian grooming standards,” and otherwise subjected to discriminatory personnel practices.

The hotel argued that the case should be moved to arbitration. The employees had signed a contract with the restaurant that included an arbitration clause, and the hotel’s lawyers argued that the lawsuit against the hotel, as opposed to the restaurant, was an attempt to get around it. The plaintiffs argued that civil rights claims shouldn’t be subject to forced arbitration and that the employment agreements weren’t clear about which corporate entity they had agreed to arbitrate with.

In February 2018, the judge ordered the case to arbitration. A.J. Dhali, the lead attorney for the plaintiffs, told BuzzFeed News that the arbitration is ongoing, with a trial before an arbitrator scheduled for September. The hotel’s lawyers didn’t return a request for comment.

Arbitration is promoted as quicker and cheaper than going to court. That can be true, said Jean Sternlight, a professor at the William S. Boyd School of Law at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, who studies arbitration. In some cases, consumers or employees may want the privacy that arbitration affords, she said, and having an arbitrator with industry or technical expertise can be more efficient than going before a judge.

But companies also can use arbitration clauses to put up barriers that disadvantage consumers and employees, Sternlight said. They can restrict how much money an individual can get if they win, shorten the deadline for filing, put the location for arbitration in an inconvenient location, or put the burden on the person filing the claim to pay the arbitrator’s fees, she said.

Companies can also block class action arbitration cases. It may not be economically viable for one employee to file a claim for discrimination or unpaid wages in arbitration, but it could be if they were joined by hundreds or thousands of other employees with the same claims, Sternlight said. In April, the US Supreme Court ruled that a contract had to explicitly allow class arbitration — if the language wasn’t clear, that wasn’t enough, the court ruled in a 5–4 decision.

“The more modern phenomenon [of arbitration] is less voluntary, less consensual in any meaningful way,” Sternlight said. ●

UPDATE

The story was updated to clarify the status of Jessica Denson's lawsuit.