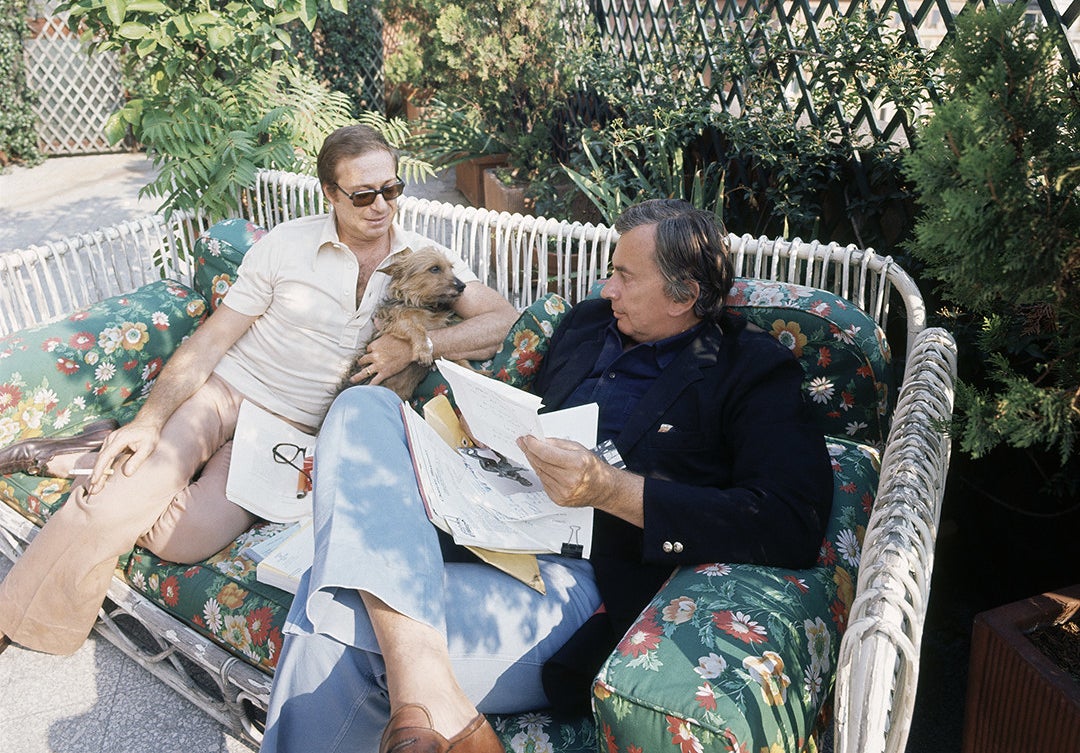

In the first two weeks of October 2017 — just as the country was reeling from stories by the New York Times and the New Yorker about Harvey Weinstein’s decades-long pattern of sexual harassment and assault — Kevin Spacey was in the sublime, sun-drenched environs of Southern Italy. He was wrapping production on the Netflix film Gore, a biographical portrait of Gore Vidal, the late literary iconoclast and public intellectual. It was Spacey’s biggest and juiciest leading role in a feature film since at least 2013, when the Oscar-winning actor began starring in Netflix’s signature drama series House of Cards.

It may very well also be Spacey’s last.

On Oct. 29, 2017 — just three weeks after Gore wrapped — BuzzFeed News published a story in which actor Anthony Rapp alleged that in 1986, Spacey made an unwanted sexual advance toward him when Rapp was 14. That week, several more men came forward with allegations of sexual misconduct against Spacey, including one man who said he’d been in a sexual relationship with Spacey when he was 14 that ended after an attempted rape. By the end of that week, Netflix had suspended production on House of Cards, announcing a month later the company had decided to move forward without Spacey on the show’s final season (which debuts on Nov. 2). But Netflix abandoned Gore entirely, and the film does not currently have distribution.

Since then, Spacey has assumed a high perch of unique dishonor within the reckoning that has consumed the entertainment industry over the past year. He is under several criminal investigations and the subject of a civil lawsuit. The damage to his career seems complete, if not irreversible.

Spacey isn’t alone in reaping the professional consequences of his destructive behavior. Everyone who worked on his previous films must now live with the films’ new, unintentionally darker meanings — especially American Beauty, for which Spacey won an Oscar for his performance as a suburban father obsessed with his teenage daughter’s best friend. Billionaire Boys Club, starring Ansel Elgort, Taron Egerton, and Spacey in a supporting role, opened in a tiny release of just 11 theaters in August and has grossed just $1,349 domestically. Netflix reportedly lost $39 million from its decision to sever ties with the actor — basically eating the cost of making Gore.

And it’s Gore that presents an extraordinary example of how the work of hundreds of dedicated people can be instantly and catastrophically recontextualized by the revelations of a single person’s sexual misconduct. According to a copy of the shooting screenplay for Gore obtained by BuzzFeed News, the film contains several scenes that would almost certainly strike audiences as difficult to absorb given Spacey’s involvement. Some scenes explore Vidal’s complicated and unorthodox attitudes toward transactional sex and sex with very young men, for example, and a graphic scene involves two transgender sex workers.

To be sure, there have been other feature film and TV projects that, in the wake of the #MeToo movement, have been adversely affected after powerful men connected to them were accused of sexual misconduct — including Amazon’s Transparent, thanks to Jeffrey Tambor; a Hugh Hefner biopic, thanks to Brett Ratner; and several Weinstein Company films, thanks to You Know Who. And after Louis C.K. admitted to masturbating in front of several women without their consent, film distributor The Orchard dropped plans to release C.K.’s film I Love You, Daddy — which he wrote, produced, starred in, and directed. C.K. ultimately bought the film back from The Orchard, and while it had at least screened for audiences at the Toronto International Film Festival, I Love You, Daddy has no scheduled theatrical release.

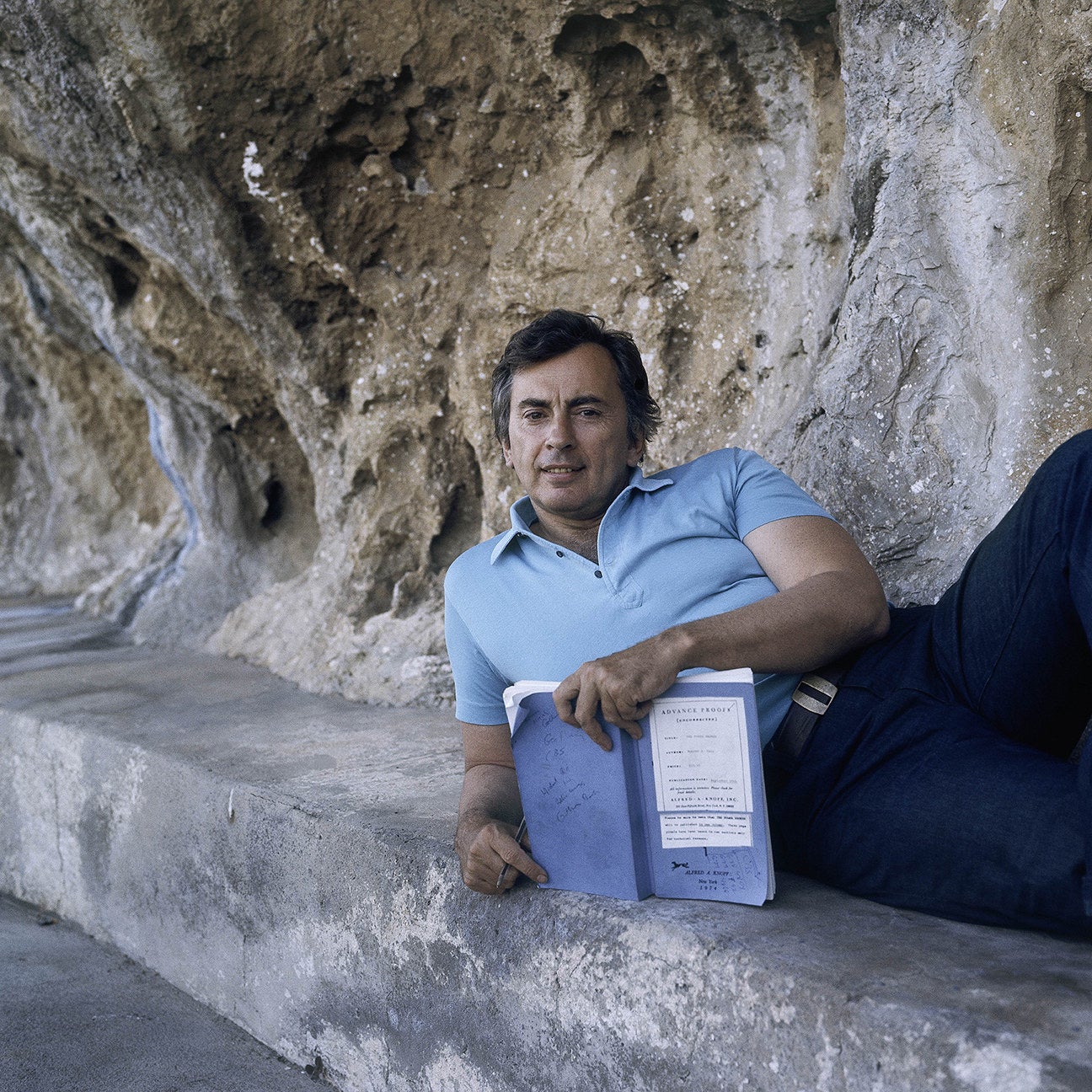

But unlike C.K., who was the sole architect of his film’s deliberately — and disastrously — troublesome storyline, Spacey was only an actor for hire on Gore. Director Michael Hoffman (The Best of Me, Soapdish) wrote the screenplay with Jay Parini based on Parini’s biography of Vidal, Empire of Self: A Life of Gore Vidal, which itself was based in part on the many years Parini spent working closely with Vidal as his literary executor. And unlike Spacey’s supporting performance as J. Paul Getty in All the Money in the World — which director Ridley Scott decided to reshoot after Rapp’s story broke, with Christopher Plummer stepping in to play Getty — reshooting Gore with another actor as Vidal would mean remaking virtually the entire film, a financial nonstarter. Spacey is the movie, and its makers are stuck with him.

No one involved with Gore — including Hoffman, Parini, producer Andy Paterson, and actors Michael Stuhlbarg (Call Me by Your Name) and Douglas Booth (Jupiter Ascending) — agreed to speak with BuzzFeed News for this story, and a representative for Netflix did not respond to requests to comment. Two weeks after Netflix dropped Gore, however, Stuhlbarg told the Hollywood Reporter that “we all have some hope that perhaps … over time there will be a chance for people to see it in the light in which it was meant to be seen.”

“When you work hard on something, you want people to see it,” Stuhlbarg added. “I think there’s a desire for us to maybe have that happen.”

Since Stuhlbarg spoke those words last year, however, Spacey’s career has only imploded further, making the following descriptions of specific scenes from Gore even more troubling for its prospects of finding a distributor willing to spend the money to release the film. What is also clear, however, is that Gore would have made for a fascinating addition to the culture’s ongoing #MeToo conversation — had the man at its center not been #MeToo’d.

Gore Vidal talks a lot about sex with “boys”

The opening scenes in Gore speed through Vidal’s failed Senate campaign in 1982. After he loses, Gore escapes to his palatial cliffside villa along the Amalfi Coast in Italy, where he falls into a severe drunken depression, picking fights with his lifelong companion and manager, Howard Austen (Stuhlbarg). Everything Howard does to get Gore to start writing again just results in a torrent of insults, until Howard comes upon a fan letter sent by Jamie Haughton (Booth), a young, aspiring writer who happens to be vacationing in Italy with his serious girlfriend, Mari (Skins’ Freya Mavor).

In an effort to revive Gore’s cratering disposition, Howard fakes a letter from Gore inviting Jamie and Mari to visit their villa and convinces Gore he wrote it in a drunken haze. Once Gore takes one look at Jamie — the script goes to great pains to underline just how beautiful Jamie is — he cleans himself up, ingratiates himself to Jamie and Mari, and tasks himself with guiding Jamie’s literary ambitions. He also begins, with his famous scholarly panache, to try to seduce Jamie.

It’s at this point that Gore begins exploring one of the central themes of Vidal’s life — the intersection of sex, power, and consent — and in doing so, unwittingly and unnervingly echoes the particular allegations of sexual misconduct against Spacey.

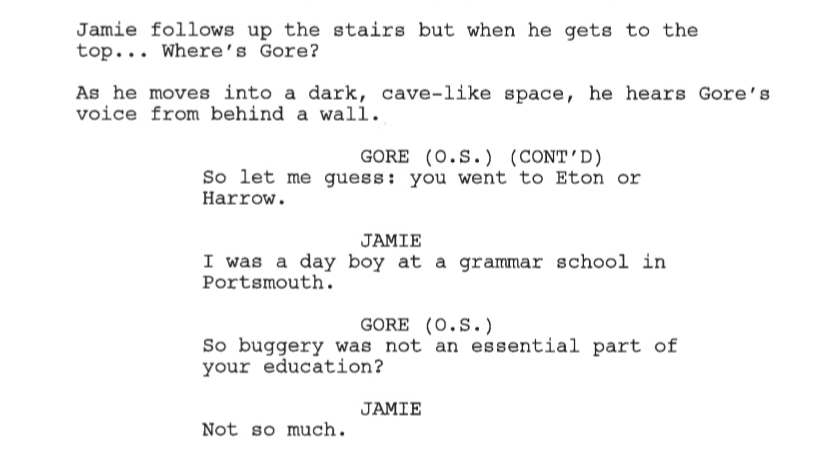

Gore takes Jamie to the island of Capri, where the Roman emperor Tiberius — whom Gore mistakenly believes is the subject of Jamie’s book — maintained a palace. As they wander the ruins, Gore tries to tease out details of Jamie’s upbringing and how much he might be keen on sex with men.

A bit later, Gore tries a different tactic, telling Jamie that Tiberius was “a bit of a pervert.” When Jamie tries to protest, Vidal pivots to the Roman historian Suetonius.

“You disagree with Suetonius. Good. I’m with you,” Vidal says. “Still, it strikes me that the tales of [Tiberius] swimming with all his little boys… his ‘little minnows’ as he called them. Nibble. Nibble. Nibble. That’s hard to make up.”

As drama, the scene admirably captures Vidal’s rarefied intellect and happily debauched worldview, while raising the stakes on just how far the tension between him and Jamie will go. But with Spacey speaking these words, audiences could all too easily think instead about the actor’s own alleged behavior around, as Vidal says in the script, “little boys.”

Gore Vidal hires two trans sex workers, and things get intense

After their trip to Capri — and after Gore realizes that Jamie’s subject is really a populist Roman politician named Tiberius Gracchus — Gore decides he has to take Jamie for a weekend in Rome. Again, the trip ostensibly is meant to further illuminate Jamie’s understanding of whom he is writing about, and they do visit the historic site of Gracchus’s murder before Gore sharply lectures Jamie for focusing on Gracchus’s high-minded ideals without understanding him as a flesh-and-blood man.

So Gore decides to push Jamie into exploring his own unplumbed depths. After they happen upon Gore’s old friend Rudolf Nureyev (Nikolai Kinski) — the famed Russian ballet dancer who often frequented Vidal’s Italian villa — the three men retire to Gore’s apartment in the city. Gore’s servant Sanjeev (Phaldut Sharma) then appears with what the script describes as “two tall beauties, one coffee-colored, one blue-eyed and blonde, dressed in low cut dresses in fishnet stockings.”

The women, named Marcella and Petra, begin to dance suggestively together, and Rudolf joins them. As Jamie takes in the scene, Gore hands him a Roman lamp, onto which is carved “a male couple, an older man taking a youth from behind.” Gore launches into a lesson about sex, Rome, and domination. In antiquity, he argues, “there was no stigma attached to fucking a man as long as you were the fucker, the penetrator… as long as you were the imperial conqueror.”

At this point in the script, Jamie follows Gore’s gaze back to Rudolf dancing with Marcella and Petra, in time to see Rudolf lift Marcella’s dress “to reveal a big, dark cock.” Then Rudolf strips Petra, revealing “a second cock in a nest of platinum pubic hair.”

Gore’s filmmakers certainly had no intention of reminding their audience of what Spacey has been accused of.

As Jamie watches the trio — “transfixed,” as he’s described in the script — Gore continues his oration. He says that Marcella and Petra would be referred to as “infamia” — in other words, “prostitutes, slaves, entertainers…those a freeborn Roman man could fuck with impunity.” Now, if modern audiences know anything about Gore Vidal, it is likely that he is the author of the 1968 satire Myra Breckinridge, recognized as the first major novel about a transgender woman. It is not a subtle piece; for example, in the novel, and the 1970 film adaptation starring Raquel Welch, Myra anally rapes a man with a strap-on dildo. Which is to say that this particular sequence in Gore would not strike an audience in 2018 as the most progressive depiction of trans sex workers; but it is also, at the very least, in keeping with the particular obsessions of its main subject.

But when Gore guesses, correctly, that Jamie is “hard,” and reassures him that “You’re hard because you’re human and right now it doesn’t matter if pretty Petra is a boy, a girl or everything in between,” it’s startling to remember that Kevin Spacey is the one speaking these lines — a man who has been accused of aggressively groping the genitals of many young men without their consent, of performing a sex act on a man while he was sleeping, and of attempting to rape a 14-year-old boy. Any movie with a major star is going to evoke at least some of that actor’s baggage — often, the filmmakers are counting on it. But having conceived, written, and shot their film before any of the stories about Spacey had come to light, Gore’s filmmakers certainly had no intention of reminding their audience of what Spacey has been accused of. With a sequence this fraught and intensely sexual, however, they’re all but guaranteed to.

Gore Vidal evokes Kevin Spacey in a bunch of small ways too

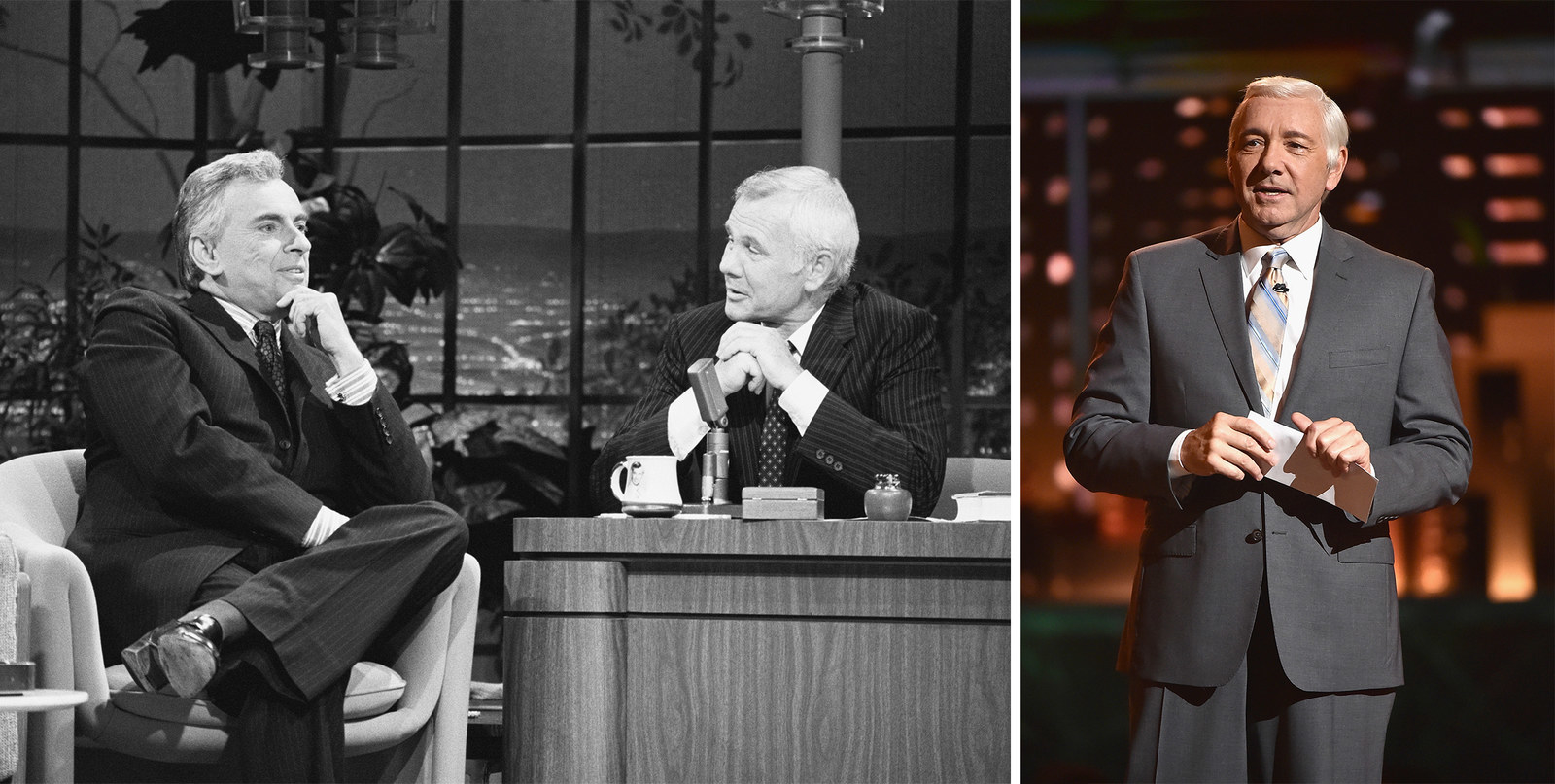

Those two sequences are the most eye-catching in terms of their regrettable and unintended reminders of the man playing Gore Vidal, but they are far from the only ones. Gore’s very first scene is set at The Tonight Show, as Gore talks up his campaign for the Senate. An actor, Jim Meskimen, plays host Johnny Carson, but there are few things Kevin Spacey has liked doing more in his career than showing off his impersonation of Carson.

Then there’s Gore’s constant, excessive drinking throughout the film. At one point, Jamie watches in horror as a fall-down intoxicated Gore throws back another drink, barely hitting his mouth, and letting most of it dribble down his chin. Gore is drinking in the scene at a party on a yacht with Leonard Bernstein (Griffin Dunne), in which Gore, frustrated he’s not the center of attention, strips “buck ass naked.” And he’s drinking in the scene in which he convinces Jamie to swim naked in his villa’s pool, begins kissing Jamie’s face, and refuses to release Jamie once he starts struggling to get away, saying, “Gore, no…”

One of the most common elements of the stories about Spacey’s misconduct shared by many of the men who have come forward, including Rapp, is that Spacey was exceptionally drunk. In his statement responding to Rapp’s story, Spacey even apologized, sort of, to Rapp “for what would have been deeply inappropriate drunken behavior.” (Spacey has either denied, through a lawyer, all the other allegations against him or not responded to them at all.)

If there is one resonance with Spacey’s past that Gore’s filmmakers might have anticipated, however, it’s with his performance as Frank Underwood, the ruthless, self-serving, ideal-free politician at the heart of House of Cards. In his campaign for Senate, Gore was the polar opposite, a firebrand populist whose message as it’s presented in the script most closely suggests Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign.

“Your elected officials aren’t speaking for you or me,” Gore says at one rally in the script. “They’re speaking for AT&T and Mobil Oil and Chase Manhattan Bank and David Rockefeller. Because those are the people that sent them to Washington.”

The idealism of Gore’s campaign is what draws Jamie to want to talk with Gore in the first place, and having a young, beautiful man be so enraptured with his better angels begins to destabilize Gore’s image of himself as, in Howard’s inimitable words, a “megalomaniacal cunt.” That tension drives the story, and suggests a movie that could explore an endlessly complex queer man — a man in constant battle between his towering talents and his corrosive behavior — in a way few, if any, films ever have. One could see why Spacey, given his own frightful demons, might even see some of himself in such a character. And why audiences would too. ●